Let’s Turn the Black Nod Into a Collective Nod

Uciane Scarlett, principal, Oxford Sciences Innovation

I first met Ken Frazier, the CEO of Merck, at the JP Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco in January 2018.

It was my second year as an operator in biotech. I was still getting familiar with the whole bewildering experience of JPM. I was trained as a cancer immunologist at Dartmouth, did a stint in life sci strategy consulting, and had started to realize what I might do with the rest of my career in industry.

At the time, I was the director of business development & strategy for a little-known cancer immunotherapy startup, Compass Therapeutics. I didn’t know a lot of the people swarming around Union Square.

Yet there I was at the rather large Merck reception with several hundred people at the Fairmont Hotel with the CEO of my then company, working the room, making small talk. As would typically be the case, there were maybe 4-5 black people in the room.

When I noticed Ken making the rounds, my CEO had to do a double-take. It can’t be, why would the CEO of Merck attend such a large event with a lot of people likely to hound him with endless unwanted business pitches?

Then Ken saw me and gave me the “black nod.”

For those unfamiliar, this is a nod between black people as a way to say, “I see you; I acknowledge you”.

Then something surprising happened. Ken Frazier, one of the most powerful people in the pharmaceutical industry, and one of the most powerful people in all of Corporate America, came over to our little group. With great enthusiasm, he said he was looking to connect with everyone in the room. He had no idea what I was working on, or whether it might be something of interest to his company. He just made me feel welcome, and asked some questions that showed his curiosity about who I was and what I do.

We never spoke about race. That night I not only saw a black man acknowledging a black woman in a room where we represented <1% of attendees, I also saw a grounded individual with admirable humility.

Last Monday, Ken showed another side of himself during an extensive CNBC interview. He expressed grief and frustration for the killing of George Floyd. He chastised the actions of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. Importantly, expressed the need to keep the conversation going even after the protests end.

The second part of his 17-minute interview rose to an emotional crescendo as he built on a plea to do more to support African Americans’ participation in society. He spoke of his own opportunity provided by social engineers in Philadelphia which allowed him to be one of nine African Americans to get a rigorous education that set him on a path for success. He emphasized how someone intervened and provided him an opportunity.

Someone essentially said “I see you, I acknowledge your opportunity gap”.

It was poignant. In that instance, I reflected on the numerous images, videos, audio clips that have been in our newsfeeds and social media platforms. I heard the emotions in his voice, I saw it in his face. I was moved to tears.

I moved to the US from Jamaica and started grad school at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire in 2006. That year I was the only black student in my class, and one of four black students in the Arts & Science PhD program at Dartmouth. I got my PhD in cancer immunology in 2011 – right around the beginning of the cancer immunotherapy revolution.

Although I’m an American citizen, I won’t write as if I’ve fully experienced what it’s like growing up black in America. The novel “Americanah” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie mimics my nuanced experience and reflects many healthy debates I had with classmates of color during grad school.

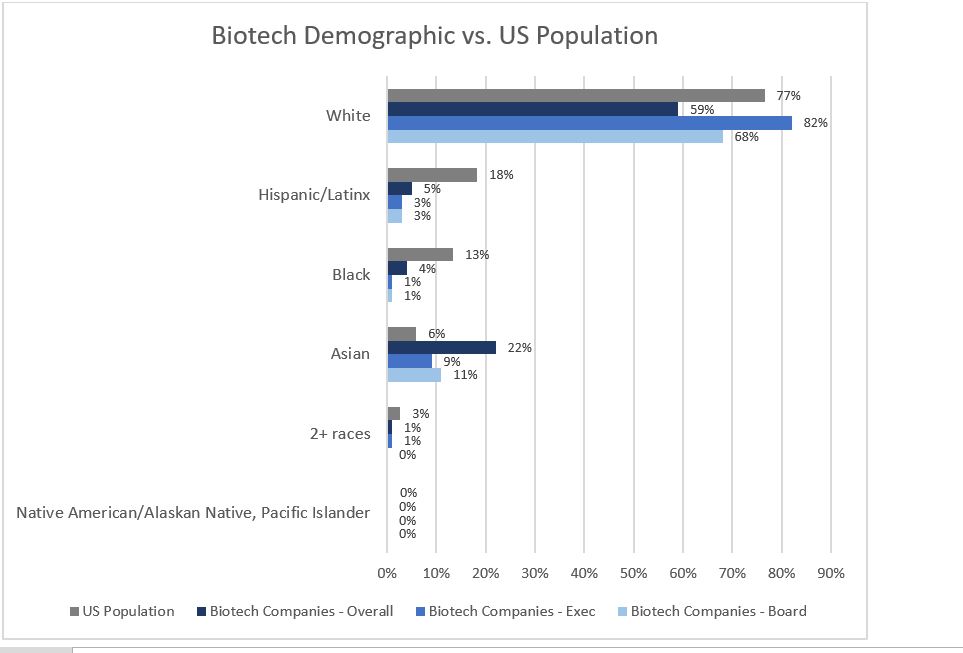

Still, I am a black woman and until recently – as I moved to the UK last December – fell within the estimated <5% (BIO 2020 report) of the US biotech workforce.

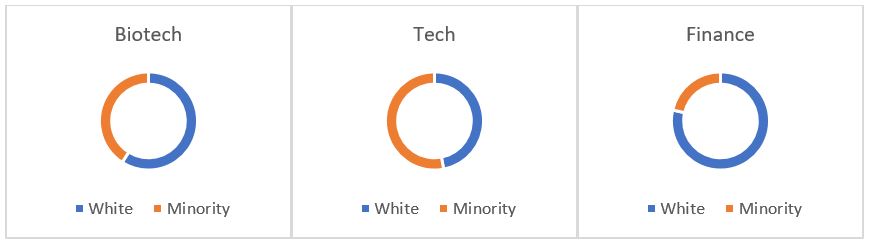

The biotech industry is fairly siloed, but based on meritocracy. It is one of the most diverse in the US relative to other highly specialized sectors, such as Finance (Figure 1). Still, blacks/African Americans represent a grossly underrepresented group in biotech when compared to the overall US population (Figure 2).

Today, racial justice and diversity, equity, and inclusion are commanding people’s attention in America like never before. The appalling killing of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police, and other recent acts of violence against African Americans, have triggered this awakening. Coupled to the latest economic downturn and psychological pressures of lockdown and social distancing, the societal response and commentary is global.

For the first time in recent history we’re seeing corporate America, including biopharma companies, like Novartis, J&J, and Gilead, show public support with press releases and statements that go beyond the usual rhetoric.

But how do we translate the words, and the expressed values animating the words, into meaningful action? How do we do more? How do we continue to build an industry based on meritocracy, but that is more inclusive? How do we build a path for more underrepresented minorities towards higher education, and ensure we continue to tap into the pool of 3,000+ Black/African American doctoral recipients – 500+ in life science – in 2018?

Ken Frazier started to answer many of these questions during his CNBC interview, but I’ll build on his commentary with a few additional points below:

Start at the level of the individual

Boston is the biotech hub, with $4.8B venture capital investment and employing >70,000 individuals across the industry in 2018. About 10 miles south of the cluster of companies in Kendall Square is Roxbury, a neighbourhood I frequented during my role at Big Sister Boston. I enjoyed connecting with the girls in the program, which was committed to providing opportunities to underrepresented girls, and often drove them around Kendall Square as a way to ignite excitement for science and the biotech community. As humans we make deeper connections with the familiar. To many Americans, minority neighbourhoods are unfamiliar, individuals within these neighbourhoods are unfamiliar. Forming deeper connections with underrepresented groups exposes the unfamiliar, it creates the comfort required to speak openly about racial matters, it creates the foundation necessary to define meaningful actions, and establishes a platform for voices to be heard.

Go beyond press releases and statements

1. Hire outside of network

When hiring we have natural biases to look within our networks. Oftentimes we look for individuals from select colleges, former colleagues, or members of professional or social groups. Tony Coles, CEO of Cerevel Therapeutics and former CEO of Onyx Pharma reflected on how he achieved 40% people of color on the executive team of Onyx. His marching orders for his head of human resources were simple, find him the best people.

2. Extend patient-specific diagnostic & therapeutic platforms to underserved groups

In an era of personalized, individualized, and genetic-based therapies, the commercial model predominately supports a European demographic, thus limiting access to underrepresented groups. This is commonly seen in early-stage product development where a company focuses its platform on a major market segment, but often does not expand to minority groups as their platform matures. 23andMe, a genetics service provider who generates reports on health predispositions and traits, recently acknowledged that their product was Euro-centric and recognized they were part of the problem. While admirably forthright, it’s unclear how they intend to address this limitation, but providing underrepresented groups access aligned with potential socioeconomic limitations will be a necessary step forward.

3. Aim for fitting representation of race and ethnic minorities in clinical trials

Blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in clinical trials for diseases prevalent in these groups. A 2019 AJMC study reported that blacks and Hispanics were enrolled at 22% and 44% respectively of their expected rate of cancer, in contrast to whites and Asians who were enrolled at 98% and 438% respectively. Companies like Pfizer have launched initiatives to recruit participants who are more representative of the patient populations under study, but can they do more? Education is a key limiting factor for clinical trial participation as underrepresented groups often have a misunderstanding of the cost, risk, and benefit of participation. There is also a legacy of mistrust that must be acknowledged and confronted. Coupling targeted education with innovative recruiting platforms, ensures therapies are developed suitably for diseases where minorities are predisposed.

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said:

“the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story”.

We’re energized and hungry for change. We’re well-positioned to change the single story. There is so much more that we can all do to create a more equitable world, through our individual actions, and through policies at our companies.

I hope we can all build on the “black nod,” and turn it into the “collective nod.”

Figure 1: Biotech – survey of 33 biotech company respondents who completed questions on race/ethnicity representation. Tech – survey of 4 tech companies, Google, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft. Finance – finance & insurance workforce (Sources: BIO – Mix Matters Annual Report, Measuring Diversity in the Biotech Industry, 2020; Wired 2019; US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019)

Figure 2: Survey of 98 biotech companies in 2019; showing 33 that completed questions on race/ethnicity representation against US 2019 census demographics (Sources: BIO – Mix Matters Annual Report, Measuring Diversity in the Biotech Industry, 2020; US Census Bureau)