The US is Teeming With SPACs, Why is the UK at Zero?

Uciane Scarlett, principal, Oxford Sciences Innovation

Biotech startups from the UK traditionally have a financing strategy that leads to one of two places – the NASDAQ or the NYSE. This means learning how to follow a US-centric playbook.

About 10 percent of the biotech IPOs on the US markets this year come from companies based outside the US. This is consistent with trends of the past and something my firm, Oxford Sciences Innovation (OSI) expects to continue for years as our 5-year old life sciences portfolio matures.

Financial capital is so abundant in the US that we now see large “blank checks” being bandied about in search of promising startup companies.

These Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, aka SPACs, more recently are being run by private equity and venture capital firms looking to the public markets as a unique channel to raise large sums of capital other than traditional limited partners that come from the world of pension funds, endowments, and foundations.

Bruce Booth’s blog on Oct. 15 provided a good summary of the trends observed regarding healthcare SPACs. In 2020, almost 24 healthcare SPACs were raised or announced with the goal of putting $3.4 billion to work in emerging companies. For some perspective on how much money that really is, Booth compared the boom in SPACs to the entire US healthcare IPO market in 2019.

That year, before the pandemic, biotech companies raised a total of $4 billion through IPOs.

In the past, SPACs weren’t in favor with US investors. But now there are entirely new pools of capital seeking biotech opportunities. They are turning to biotech specialty funds for help in identifying opporutunities. The list of quality investors taking advantage of the SPAC boom this year includes 5AM Ventures, MPM Capital, Deerfield Management, and RA Capital, among others.

The resurgence of SPACs is being driven by the volatility in the markets amid the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with rising awareness of opportunities in biotech, according to Bloomberg and Pitchbook in their 2020 COVID-19 market impact reports. SPACs have their appeal for healthcare companies because they present a fast and cost-effective way to raise capital.

Now that prominent investors have entered, SPACs also provide the opportunity to have a high-quality healthcare investor as a sponsor. That’s an important signal to generalist investors seeking to separate the wheat from the chaff.

For investors who sponsor these blank check entities, it’s a familiar private equity structure with liquidity, regulations, and transparency provided by well-functioning capital markets. The typical financial structuring of a SPAC would consist of 3-10% capital provided by the sponsor in order to identify assets and operate a nascent company within a 18-24-month window. Once that initial work is done and all the financing flows into the SPAC, the initial sponsors, on average, own up to a 20% equity stake. The rest of the money comes from investors who follow the leader (the sponsor). It’s a fairly lucrative line of work for those firms seen in the marketplace as worthy of being a sponsor.

So, there are plenty of reasons why investors and companies would want to get in on this trend.

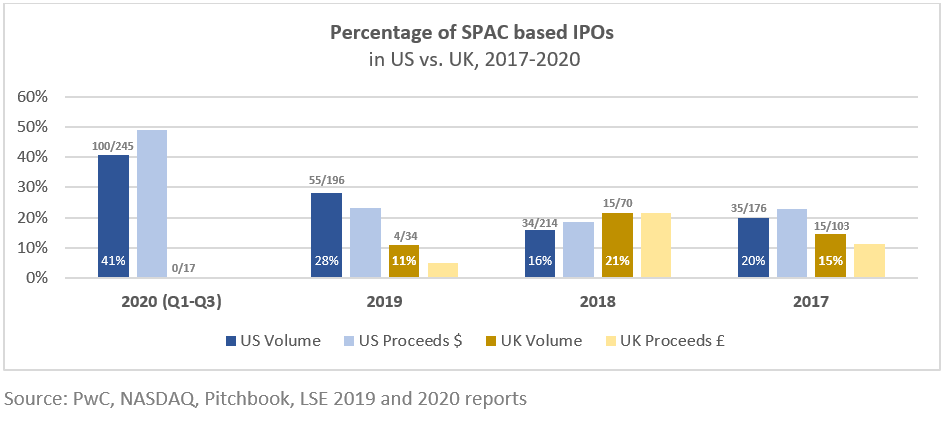

Why then, with about 100 SPACs launched in the US already in 2020, aren’t we seeing this activity in other established markets like the UK? In the UK – a region with a variety of attractive biotech startups and a steady pipeline of IPO candidates – why do we see exactly ZERO SPACs in 2020?

The UK has experienced SPAC surges, according to data compiled by Paul Hastings, a UK-based law firm. The years following the 2007/2008 financial crisis, when public investors sought alternative structures, provided one such opportunity.

Some context is required to understand what’s going on in present day. When I asked Nooman Haque of Silicon Valley Bank London, he reflected on the public markets of 20-25 years ago, when the dot-com boom coincided with the debut of the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) of the London Stock Exchange (LSE).

The AIM caters to later-stage, often revenue generating or lower-risk companies and provides them with an opportunity to grow rapidly. Over 2,500 companies have been admitted to the AIM, and those companies had collectively raised more than $140 billion through 2019. Haque highlighted the early 2000s and how the financial crisis made it more difficult for companies to raise capital for a few years, and eventually created something of a brain-drain from the UK. He concluded that the country ended up with fewer technical analysts who could make credible recommendations on stocks to generalists.

The current UK public market now has a lean analyst base and narrower set of healthcare investors. The result is a lower volume of coverage overall and coverage that exists tends to be tightly concentrated in certain areas, such as genomics.

One year ago, shortly after moving to the UK, I attended a dinner hosted by Lazard & Co, a London-based investment bank. The theme was “Genomics Innovations” and we discussed the immense opportunity within the UK relative to other regions, especially given the role of the national health record system operated by the NHS.

The UK is within reach of cheap, high-volume gene sequencing, meaning it has the opportunity to link genomic databases with clinical manifestations of disease – something notoriously difficult in a place like the US, with a decentralized, privatized set of healthcare providers and insurers. This has contributed to a heightened sense for measures for success, as well as an increased appetite for innovative companies with genomics platforms by UK analysts covering healthcare.

So, while Haque is correct in the reduced breath of coverage, the UK retains significant expertise in not only genomics, but also tools, diagnostics, and novel models for IP, commercialization, and financing.

This is exemplified in the fact that a majority of small-mid cap healthcare companies listed on the LSE/AIM, broadly fall within these categories:

- Tools and services, e.g. Horizon Discovery, which raised $113M in 2014.

- Medical devices and diagnostics, e.g. Creo Medical whose market cap more than doubled to $260M in 2019 after it IPO’d with a market cap of $103M 3 years prior.

- Novel or innovative financing models, e.g. Syncona, a life-sciences investment trust, which came to market through a reverse merger into BACIT, which raised >$500M 3 years prior, in 2016.

Typically, small-mid cap companies within the categories outlined above tend to be thinly traded on the NASDAQ. That tends to be the case, even after they raised large sums via IPO.

Case in point: Oxford Immunotec, a UK-based company and maker of tests for latent tuberculosis raised $64 million on the NASDAQ in 2013 – a choppy year in the markets, before things picked up in 2014-2016. Nooman Haque noted that Oxford Immunotec might have had a more vibrant post-IPO market experience if it had listed on AIM, instead of the NASDAQ.

Furthermore, select US-based companies have chosen to list on the LSE in past years:

- Tools and services, e.g. Maryland-based, MaxCyte was one of the top-4 performing IPOs in 2016 on the LSE, with a >200% performance almost a year after it IPO’d.

- Novel or innovative R&D models, e.g. Boston-based, PureTech Health has nearly tripled in value from its 2015 LSE IPO and is now in the FTSE250

Some US based companies have expressed interest in listing in a region where investors understand their model. For example, when Boston-based Allied Minds listed on the AIM in 2016, its CEO, Chris Silva, highlighted that their IP commercialization model was deeply understood by UK and European investors. That decision made sense, because UK investors were familiar with comparable models, such as Sheffield-based Fusion IP, founded in 2001.

These examples each tell a story, but how are the UK healthcare markets performing overall, compared with the US?

UK investors are doing better than most would expect. In Q2 2020, the AIM 100 and AIM All Share’s percentage change was on par with that of the NASDAQ 100 and NASDAQ Composite at ~30%. While some of this growth was forecasted, the AIM listed diagnostic companies Novacyt and Genedrive shot up by a remarkable 365% and 894%, respectively, by Q3.

Not surprisingly, these companies have COVID-19 offerings that captured significant headlines and investor interest.

Additionally, the LSE remains more diverse vs. the NASDAQ when it comes to its investor base. For example, an LSE 2018 Life Sciences report highlighted that 31% of the domicile investors in securities in London were North American and included marquee names like Vanguard, State Street, Wellington, and BlackRock. The LSE has attracted global investors for several reasons, including lower underwriting costs and lower rates of litigation.

With this obvious opportunity, why has no group looked to the LSE in 2020 for a SPAC?

Several factors come to mind:

- The COVID-19 pandemic: Not really; in 2020 we’ve seen strong performance in healthcare relative to other sectors, like automotive and travel. Healthcare is where investors are placing their surplus cash in 2020.

- Market dynamics: the remaining uncertainty around Brexit, possible trade wars and a potential economic slowdown are additional factors that might be making investors “gun shy” about investing in LSE/AIM listed SPACs.

- High-profile failures: the wind down of the Woodford fund has possibly impacted market sentiment, but it’s unclear the overall degree of impact.

- Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE): with a developing healthcare market in Asia, the launch of the HK Biotech Index, and the 2.5x increase in the number of healthcare company listings observed to date, there is clearly a new international player in town. The HKSE has seen >$1B in SPAC volume in 2020!

Stefan Hamill, a Senior Life Sciences analyst at Numis Securities in London, however, emphasized Brexit as a key driver which has impacted international allocations to the UK. This has seen global fund flows underweight the UK market for the last couple of years.

Numis has reported record revenues of late, Hamill said. Only 2% of revenues of the investment bank’s revenues were related to IPO fees – a remarkably low number. As recently as 2014, fees from IPOs were greater than 20% of revenues for Numis. Today, 20 percent of its corporate fees come from helping private companies raise capital, Hamill said.

There are signs of a return of the UK IPO market in the most recent quarter, Hamill said.Partly, this is because funds are beginning to get more comfortable with investing now that they can see a post-Brexit future.

While we cross our fingers that there is some sort of a Brexit deal in early 2021, which would facilitate a continuation of this trend, Hamill also highlighted lingering regulatory issues to navigate to facilitate SPACs. Given UK guidelines, SPAC sponsors in the UK have fewer options than in the US. Their US counterparts can redeem their shares if they don’t want to invest in the underlying target. UK sponsors cannot optout.

In short, there needs to be a reform of the LSE to enable UK’s participation in a more meaningful way given the rise of quality sponsors and the obvious opportunity within the UK market for healthcare companies.

The LSE remains 15-20 years behind the US, but there is a density of quality investors and analysts who understand distinct areas within healthcare, possibly better than other regions.

Coupled with greater comfort around the impact of Brexit, high quality US (and for that matter, UK VC funds) sponsors should be considering the UK for SPACs in 2021.

Several pieces of the puzzle are already in place – technology, management teams, and pools of capital looking for biotech opportunities.