Once Vaccinated, What To Do With Masks?

Larry Corey, MD

Contributing editor: Chris Beyrer, MD

Once I’m fully vaccinated, should I still wear a mask?

This is probably the biggest public health policy question facing us today. It’s an issue each one of us will have to ask ourselves as the U.S. mass vaccination campaign continues to roll out, especially when many people around us aren’t yet fully vaccinated.

No one likes masks, including me. But I understand how many gazillion viral particles can be put on the head of a pin and how many gazillion viral particles can be emitted through a sneeze, or while talking, or eating. I know how easy it is for other people around us to inhale those viral particles, and then come down with a serious case of COVID-19. And I understand how evolution has made this the mode of transmission for hundreds and hundreds of viruses—far too numerous to list here—little critters that were here on the planet well before us.

The good news in the fight against COVID-19 is that we now have three very effective vaccines—two mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna), and one Ad26 (Johnson & Johnson)—approved in the U.S. under Emergency Use Authorization. These vaccines provide personal protection against symptomatic COVID-19. That’s great news, now that more than 30 million Americans have been fully immunized, and perhaps 100 million Americans have some measure of natural immunity from prior bouts with SARS-CoV-2 viral infection.

But what about those unvaccinated persons around you? Are they protected? Can you still acquire the virus unknowingly and transmit it? The CDC put out new guidance on social distancing for fully immunized people on Mar. 8. The headlines focused on fully vaccinated people being able to gather indoors with small groups of unvaccinated friends and family, unmasked.

Essentially, it was a green light to go visit the grandkids and hug them.

We need to think about this new guidance and what we know and don’t know about COVID-19 transmission.

First, let’s look at what happens when you come into contact with the virus and how protection works in your body.

When the virus lands on your hands and you touch your eyes or your nose or your mouth, it really becomes a race between your immune response and the virus’s ability to invade cells and start replicating.

The winner of that race is determined by a number of factors. There’s the infectivity of the virus itself, the inoculation load, the strain of the virus, and your own innate and adaptive immune response.

How good are the first “soldiers,” the innate immune system cells often found in the mucosal lining of the nose, and just under the skin? These cells are often not primed by vaccination. Then there’s the question of how quick are the second soldiers, the B cells that produce specific antibodies, and the killer T cells that have memory for certain pathogens. Do these second-line defenders get into the nose? If so, how many get into the nose?

There’s a fair amount of work that’s been done on what we call the battlefield between the host and the virus. And for many fast-replicating viruses, the half-life of a viral-infected cell is 20 to 40 minutes. So, every 20-minute delay in an immune response can lead to a doubling, sometimes a tripling of the virus. This interplay tends to happen in what I’ll call staccato time; it certainly is not adagio (slow tempo).

Once you’re vaccinated, we know from well-controlled clinical trials that you are protected from getting severely ill or dying. What we don’t yet know is: can the virus still infect you and replicate at a high enough titer that you could unwittingly transmit it to someone else?

That’s the question we’re asking today. If the person is vaccinated, this may not be a big deal. But if they’re not vaccinated and they have an underlying medical condition, and they breathe in SARS-CoV-2 viral particles, then we could have a problem. A problem that leads to hospitalization or worse, death.

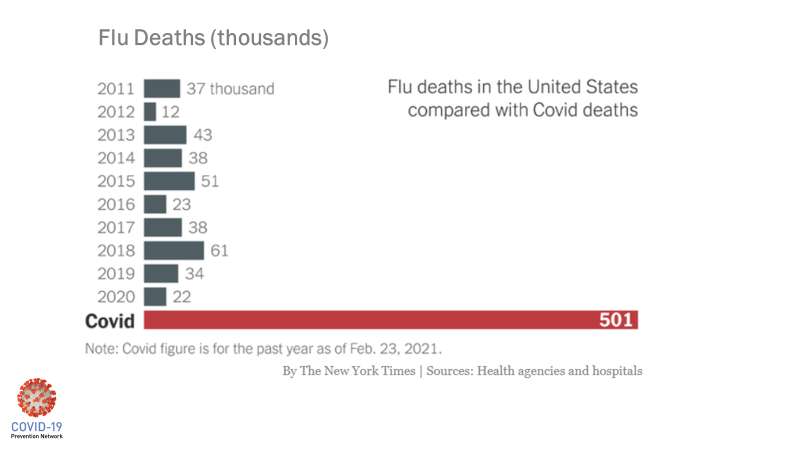

The potential severity of COVID-19 continues to stagger the imagination. It’s not like the flu, despite some public assertions from a year ago.

This graph illustrates the point:

It’s this knowledge that I carry with me from day to day.

I try to remind myself, “Larry, you’re vaccinated, but a lot of people aren’t. In fact, 90% of the people walking around are not vaccinated and you do not have the luxury to give up your responsibility to protect them.”

This brings me back to the issue of wearing masks. Once you’re vaccinated, it’s really not about you at all. It’s about the other person. Maybe a friend or family member or neighbor or colleague that attends the same event or gathering but has not had the opportunity to be vaccinated. Or even someone who has chosen not to be vaccinated: do they deserve to get ill?

One might ask, a year into this pandemic, why don’t we know whether being vaccinated will prevent transmission? We don’t know this because the kinds of studies required to look at transmission are different from the ones designed to test vaccine efficacy. The clinical trials testing vaccine efficacy showed personal benefit—in other words, if you get vaccinated, will you be protected? And the answer to that as we’ve seen is Yes.

But looking at transmission is a different matter altogether, and requires an entirely different study design, a different set of volunteers, and all the time and money required to get a rigorous answer we can count on.

In the phase 3 trials we conducted through Operation Warp Speed, there were thousands and thousands (approximately 30,000 participants) who were tested regularly (approximately once a week) to see if they got symptomatic COVID-19. But to test whether the virus was colonizing in the nose — without visibly detectable symptoms — would have required near-daily testing. And if you pause to consider that—30,000 persons over five months—with each person coming in daily to get their noses swabbed, it would have become impossible to test all the cultures in a timely way. We would have been diverted from defining vaccine efficacy.

It is possible to take fewer people and do what we call a transmission study, which is currently being conducted with the mRNA vaccines. We will look at vaccinated versus unvaccinated persons and define if vaccination prevents you from transmitting the virus.

This will require intensive contact tracing—looking at the contacts, who got infected, who didn’t? Who came first; who came second? Can we define exactly whether this person got it from that person? Sometimes the genetics of the virus allows one to do that.

The emerging variants also complicate things because they have been shown to be more infectious. For example, the B.1.1.7 strain first seen in the UK has been shown to cause 30% more infections. It appears to be shed for a substantially longer period of time than the G614D strain that has been circulating in the US for the last 10 months. That means people have more opportunities to spread it to others when they are doing ordinary things out and about in the community.

As the virus adapts, these new strains will cause a stress on vaccinations. But I think we can almost be happy that we’re doing the transmission study during the period of time when the virus is changing because we really are getting to the relevant issue of how well these vaccines perform when the virus is starting to mutate.

We are getting to answers, but it will take some time. With a little luck, the transmission study will show the mRNA vaccines are spectacular at preventing people from getting sick from COVID-19, AND preventing people from transmitting the SARS-CoV-2 to others. Or if you do acquire the virus from a vaccinated person, perhaps we’ll see the viral loads you take in are trivial, easier for your immune system to handle, making it far less likely that you would transmit it to anyone else.

I’m hoping that’s the result because I want to take off my mask. But until we know this with reasonable certainty, or at least until more of our population is vaccinated, then public policy—and individual conscience—should mandate mask use in public spaces and no more than small gatherings in our homes. The CDC guidance of Mar. 8 is clear that fully immunized people can meet each other at home, in small groups, without mask wearing and social distancing, but we’re going to have to maintain vigilance in public spaces, at work, on public transport and at schools as they reopen. Because mathematical modeling shows that without adhering to these measures, we could double the deaths.

How each one of us behaves makes a difference. Together, we can markedly influence the surges associated with this virus and potentially save lives.

Dr. Larry Corey is the leader of the COVID-19 Prevention Network (CoVPN ) Operations Center, which was formed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health to respond to the global pandemic, and the Chair of the ACTIV COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Trials Working Group. He was intimately involved in the planning of the phase 3 vaccine studies conducted under the funding auspices of Operation Warp Speed. He is past President and Director and Professor in the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; and Professor of Medicine and Virology at University of Washington.

Chris Beyrer, MD, MPH is the Desmond Tutu Professor in Public Health and Human Rights at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. A professor of Epidemiology, Nursing, and Medicine, he now serves as Senior Scientific Liaison to the COVID-19 Vaccine Prevention Network, and as co-editor of this blog series.