From Fitness To Flourish: Expanding the Scope of Digital Exercise

David Shaywitz

Sometimes the most relevant digital health companies have the least elaborate technology.

More than a decade ago, I discussed UpToDate, a fairly basic medicine e-textbook, served through a web-based app. It was then, and still remains, a go-to site for timely, high-quality medical information relevant to clinicians.

There’s nothing fancy about it, it just works.

Recently, I discovered a similar resource, PrecisionNutrition, that’s focused on coaching coaches to help their clients adopt consistent healthy behaviors. What’s interesting is how PN fosters a holistic, multidimensional view of health. The company stands out against a field of competitors that tend to have a myopic emphasis on a particular aspect of physical health like weight loss or physical training.

Their stated goal is to teach the coaches they train to “transform” clients’ health, and help clients “thrive,” in the broadest sense.

Physical health, PN tells fitness coaches, is just a small percentage of “what determines your clients’ success.”

Instead, PN emphasizes a focus on a multi-dimensional view of well-being, arguing that they are all interrelated, and to improve any one of them, coaches need to consider the many components of well-being.

Not only will coaches attuned to the many components of well-being find themselves able to support their clients’ immediate goals (such as losing weight or gaining muscle), PN astutely argues, but an initial focus on fitness, say, may provide an opportunity, an on-ramp, to improve their clients’ well-being more generally, across multiple dimensions.

To me, this second part – fitness as an on-ramp to a broader opportunity to enhance well-being and to help people flourish more fully – is the profound health opportunity lurking in the consumer space.

It’s the opportunity that so many digital fitness companies, in their singular focus on driving athletic performance, may be missing.

Well-Being

At best, most of us probably think of “well-being” in an informal or casual sense; many probably share the perspective of one initial skeptic, who told Yale psychologist Laurie Santos he originally assumed, before taking her course on the subject, that it was “hippy California well-being crap.” (I can totally relate.)

Well-being, it turns out, has become a subject of serious scientific study, and represents a prominent area of focus for academic researchers and well as health organizations including the CDC and the WHO. There are treatises on the measurement of well-being, and academic centers focused on the cultivation of “human flourishing,” such as the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard, the Center for the Study of Human Flourishing at Kings’ College in New York, and the Stanford Flourishing Project.

Flourishing itself turns out to be key concept within a burgeoning academic area called “positive psychology,” which focuses on what makes us happy or fulfilled. The term was said to have been coined by Abraham Maslow (of “hierarchy of needs” fame), and popularized by Martin Seligman of University of Pennsylvania (previously best known for studies of depression, and the concept of “learned helplessness”).

Some of today’s most popular academic psychologists are associated with this school of thought, including Daniel Gilbert at Harvard (though he apparently rejects the label), and Santos at Yale (who hosts the wonderful and highly recommended “Happiness Lab” podcast).

The key premise around positive psychology, and flourishing, is the idea that thriving isn’t just about reducing misery, as critical as this obviously is. Rather, the goal of positive psychology, as Seligman puts it, is to “supplement its venerable goal” of misery mitigation with a new aim: “exploring what makes life worth living and building the enabling conditions of a life worth living.”

The question of what it means to be well, and to live a good life, is both ancient and elemental. Researchers tend to consider two formulations: a hedonic approach, focused on the idea that we’re driven primarily to make life pleasant and pleasurable, and a eudaimonic approach, which recognizes a greater range of motives, such as self-actualizing and pursuit of meaning.

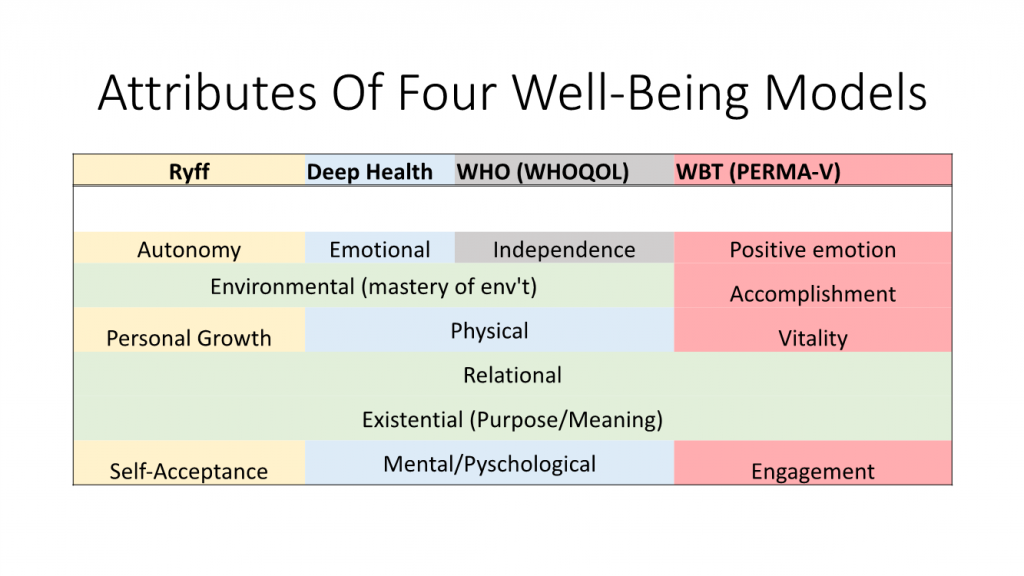

From these approaches, frameworks have emerged that emphasize different aspects.

Notes for figure:

- Ryff – Chapter 4 from Measuring Well Being, 2021

- Deep Health from PrecisionNutrition.com, link.

- WHO (WHOQOL) from WHO.org, link.

- WBT (Well-Being Theory) from Seligman, 2011, which describes PERMA; subsequent iterations of this framework (PERMA+, PERMA-V) include vitality.

While well-being – definitionally – represents a valued end in itself, there are also data linking attributes often associated with well-being to traditional endpoints such as mortality.

A 2019 review by Trudel-Fitzgerald and colleagues at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health found that several dimensions of well-being “are associated with a reduced risk of premature all-cause mortality among the general population, with small to medium effects,” associations that, critically, held up even after adjusting for confounders.

The attributes with the strongest evidence, according to this review?

“Purpose in life, optimism, and ikigai (a Japanese term that translates into happiness, worth, and benefit of being alive, and apparently capturing both eudaimonic features like purpose and hedonic features like pleasure).

According to the authors, there’s also somewhat less robust evidence linking other dimensions such as life satisfaction, positive affect, mastery, and sense of coherence to reduction in mortality. Studies examining the relationship between happiness, personal growth, and autonomy with mortality reductions “suggested no effect or were too limited to draw firm conclusions.”

Vicious vs Virtuous Cycles

In medicine, we’re all too familiar with the vicious cycles leading to the rapid downward spiral of health: an injury might impede exercise, leading to weight gain and making exercise even more difficult. The fragility of life, so easily taken for granted, can be tragically revealed by even the slightest setback, and the cascade of challenges it can produce.

How encouraging, then, to encounter a publication (thoughtfully discussed by Gretchen Reynolds in the New York Times, here) describing a rare virtuous cycle – the reinforcing findings from a longitudinal study of aging American adults that people who have a greater sense of purpose are subsequently more likely to exercise, and people who are more likely to exercise are subsequently likely to describe having a greater sense of purpose.

The study utilized an approach called a “cross-lagged panel model” in effort to reduce confounding. The bidirectional effects observed were small but statistically robust, according to the authors.

Fitness as an on-ramp to a broader opportunity to enhance well-being and to help people flourish more fully is the profound health opportunity lurking in the consumer space

The very appeal of the conclusion should remind us to keep our enthusiasm in check, and as always, seek replication and additional data.

But this study, and others like it, speak to a broader point: we need to look at physical activity from a perspective less reductive than either athletic performance – the focus of digital fitness companies (“improve your position on the leaderboard!”) – or mortality reduction – the focus of many clinicians (“exercise more if you don’t want to die sooner”).

Exercise offers a range of benefits, in many domains, perhaps including an enhancement of our sense of purpose. Similarly, attention to these other domains, as PN advises coaches, can help motivate greater physical activity.

Both physicians and connected fitness companies need to reframe how they conceptualize exercise; the opportunity is to see it not only as a path to improved cardiovascular health and performance, but as tangible starting point for greater well-being.

Entrepreneurs leading the digital exercise movement may be missing an opportunity if they don’t profoundly enlarge their ambitions, and take, as their job-to-be-done, not the need to get people fit, but rather the opportunity to help people flourish.