Obesity Is Rising; Can Health Coaches & Tech Drive Durable Behavior Change?

David Shaywitz

As we enter the holiday eating season – quickly followed by the New Year get-in-shape resolution season – let’s look at obesity challenge head-on.

Expert physicians who study obesity recognize the condition as a complex disease associated with profound health consequences. It also represents, for many health tech entrepreneurs, a high-value problem to be solved.

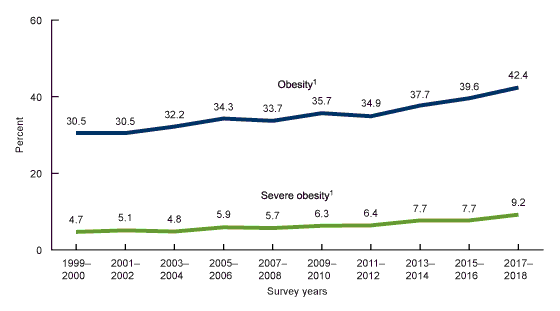

Obesity has been ratcheting upward for decades, representing a corrosive threat to national (as well as global) health. (See the data below from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and read the full CDC paper from February 2020):

More than four out of 10 adults in the U.S. meet criteria for obesity (Body Mass Index of 30 or higher), and nearly one out of 10 adults would be classified as suffering from “severe,” or “class III” obesity, with a BMI of 40 or higher.

The increase in obesity during this time period, interestingly, occurs despite the decrease in physical inactivity reported during this same time.

In other words, although more Americans seem to be getting off the couch, obesity rates keep going up.

Obesity in adults “is associated with a striking reduction in life expectancy,” according to UpToDate (an authoritative reference used in clinical practice). In addition, UpToDate reports, “obesity and increased central adiposity are associated with increased morbidity,” noting that “obesity has surpassed smoking as the number one cause of preventable disease and disability.” Significant comorbidities related to obesity include diabetes, hypertension, osteoarthritis, cancer, depression – and of course, COVID-19. As UpToDate summarizes, multiple (observational) studies “link obesity with increased morbidity and mortality” from COVID-19.

Not only are individuals with obesity at increased risk from COVID-19, but for many Americans, the pandemic seems to have prompted a hefty increase in weight. An American Psychological Association survey from March 2021 revealed that 42% of us reported undesired weight gain as a consequences of the pandemic; individuals in this category said they gained an average of 29 pounds; the median amount they gained was 15 pounds.

If there’s a silver lining related to obesity, it’s that, according to UpToDate, most of the “over 230 comorbidities and complications of obesity” that have been identified will improve when people lose weight.

The Brutal Challenge Of Weight Reduction

Yet durable deliberate weight loss remains an incredibly difficult challenge – staggeringly, almost incomprehensibly difficult.

One factor, according to MGH obesity medicine expert Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford relates to “the organ that’s most important with regard to regulating our weight – and that is our brain.” In particular, she says, the brain actively defends a weight set point, and gets “quite angry” when you lose weight, to the extent, she says, that it pushes you to return to an even higher set point – a particular problem for “weight-cycling” (i.e. “yo-yo dieting”).

Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, obesity medicine expert, MGH

And it gets worse. For the vast majority of us – 97%, she says – the brain “doesn’t retrain” on a lower weight, no matter what you do.

“Unless you do something that actually changes that brain-gut connection,” she says, citing the example of bariatric surgery, the brain “still wants to go back.”

Consequently, outside of bariatric surgery – which Stanford describes “the most effective tool available for both children and adults that have severe obesity” – maintaining a healthy weight, for most people, is destined to remain a chronic, constant, difficult, daily battle; even those who have bariatric surgery generally must remain constantly vigilant, if they want to maintain the weight loss their procedure helps them achieve.

But wait – it (somehow) gets even worse.

Six years after television’s “The Biggest Loser” competition, NIH metabolism researcher Kevin Hall, studied the 14 of the original 16 participants and discovered they had regained two-thirds of the weight they had lost during the show.

Even more discouraging, Hall found that the people who continued to exercise the most (compared to original baseline) exhibited a lower(!) resting metabolic rate (RMR). Hall says he now believes these data may represent an extreme example of the “constrained energy expenditure model” proposed by Duke anthropologist Herman Pontzer.

Pontzer’s depressing insight – evident in Hall’s data – is that our bodies tend to exhibit metabolic adaptation, meaning that lots of physical activity seems to result in a disheartening decrease in RMR, with the apparent goal of keeping total energy expenditure fairly constant. In practice, this means that when intensive exercisers aren’t exercising, their bodies seem to burn calories at a slower rate – which seems like a miserable way for your body to thank you for exercising.

Herman Pontzer, associate professor of evolutionary anthropology, Duke Global Health Institute

If there is any vaguely hopeful message from Hall’s study, it’s that the contestants who continued to exercise the most did better at sustaining weight loss (despite the compensatory decrease in RMR) than other participants. The reasons for this, he writes, “remain to be fully elucidated.”

Given the stubborn biology – not to mention the consequences of our often-obesogenic environment – it’s not surprising obesity remains a challenging and profound chronic health problem.

The Training Gap

What may be more surprising is that, despite the prevalence of obesity, and the fact that (at least according to a 2006 study from Australia), many patients preferentially look to physicians for advice on healthy eating and weight management, most doctors are apparently ill-prepared to step up.

In 2019, Stanford published a study she led examining obesity education in medical schools, residencies, and fellowships around the world, a report that concluded “there is a paucity of obesity education programs” for these trainees “throughout the world despite high disease prevalence.”

Or as she has phrased it more colloquially, “nobody learns anything about obesity as a disease, which means that even though it’s the most prevalent chronic disease not only in the U.S. but around the world, no one knows how to treat it.”

Stanford has recently extended these findings to medical specialties, and found:

“Even on medical board exams, obesity is not well covered. I can tell you that as a doctor, if it’s not on the test, we don’t think it’s important. So it’s not on the test, which means we’re not learning about it, which means that if you as a patient often are going into to your doctor and wondering why they don’t know much about the disease, it’s because they didn’t learn and it’s not necessarily their fault.”

While Stanford cites the “over 5,000 physicians in the country that are board certified in obesity medicine” as progress, she says “it won’t cut it” in the face of the “over 100 million adults that actually have the disease and the tens of millions of children that have the disease.”

Poignantly, Stanford pleads, “We need everyone to understand the complexity of the disease, especially anyone that’s on the treatment side: doctors, physicians, assistants, nurse practitioners, and the list goes on and on. Or we’re going to continue to fail our patients.”

One area where I recognize first-hand that physicians tend to lack training is in guiding patients through behavior change. I don’t know any internist who emerges from their education with a real sense of how to even think about this, beyond perhaps a conceptual introduction to the Prochaska “Stages of Change” model. While doctors consistently advise patients to undertake lifestyle modifications like reducing smoking, and pursuing diet and exercise, few in medicine expect their advice to be heeded, and it often seems to be offered more for the sake of documentation – and justifying more aggressive interventions – than based on any expectation of progress.

A physician-scientist colleague recently described a formative, and probably not that unusual experience from his own training as a medical student. A cardiologist he was shadowing would routinely try his best to scare patients, warning them they could easily die before their next visit if they didn’t shape up soon. This approach seemed to please the physician, but, predictably, resulted in minimal change in behavior.

The Promise of Health Coaching 1 – DPP Data

On the other hand, the somewhat unexpected triumph of the “lifestyle” arm of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a NIH-sponsored study first reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2002, highlighted the untapped opportunity associated with more intensive coaching efforts.

As I described in Forbes in 2012, this study examined whether several different interventions could forestall the development of type II diabetes in an at-risk population. The study included two medication arms (one of which was discontinued); one “usual care” counseling and education arm; and one “lifestyle” arm in which participants were intensively coached around diet and exercise.

The big finding was that while participants who received the medication – metformin – saw their risk of progression to diabetes cut by about a third, the lifestyle intervention group experienced a massive 58% reduction in risk.

The DPP data emphatically demonstrated what some have long believed: effective health coaching can make a real difference. At the same time, this required a Herculean effort from the coaches, who intensively and consistently engaged with the participants in this arm of the study.

One question arising from the DPP: can this approach be replicated at scale? Early efforts using group counseling, administered through a YMCA, seemed encouraging. These results, coupled with the rise of powerful personal technology, led to the birth of startups like Omada Health and others, companies seeking to combine a DPP-style intensive coaching approach with emerging technologies to achieve similar benefits at greater scale.

The Promise of Health Coaching 2 – Expert Experience

While the success of intensive coaching may have stunned some physicians, I suspect many dedicated coaches were appreciably less surprised. Given the difficulty of motivating behavior change, it makes sense to consider the perspective and experiences of those who seem especially good at it.

One example here: Canadian John Berardi, whose passion for coaching and health led him to a successful career as a coach, entrepreneur (he co-founded Precision Nutrition, and in 2017 sold 80% of his ownership in the company, then valued at around $200M), researcher, and thought leader. Berardi’s recently published book, Change Maker, offers particularly relevant insight to the unique challenges and opportunities of health coaching. (Disclosure: I have recently reviewed course materials for Precision Nutrition; I have never met or interacted with Berardi.)

As Berardi points out, “we sometimes confuse our passion for health and fitness with actual skill in helping others improve their own health and fitness.” He emphasizes that “while having knowledge is a good and necessary thing,” for health professionals, the “desire to display knowledge” can be counterproductive, since “you’re not in a knowledge-first business but a people-first business.”

Doubling down on that point, which may make some physicians and other health professionals bristle, Berardi argues:

“Unless you’re a full-time researcher or a professional philosopher, you’re not in a knowing profession, you’re in a doing-stuff-with-people profession. That means you’re accountable for how you are with people and how often those people get results (as opposed to how much you know, how smart you sound when sharing it, or how elegant your solutions seem on paper).”

John Berardi, co-founder, Precision Nutrition

(This also relates to the need for medical therapies to deliver real-world performance, vs clinical trial performance, as I’ve discussed here and elsewhere.)

Berardi also explains the importance of deeply understanding the people you are trying to help, of “asking great questions and then deeply, actively listening to the answers,” and of building upon what someone is already good at, versus telling them, in effect, their success requires they become someone else.

Also useful, he says: focusing on “behavior goals” rather than “outcome goals”; “approach goals” rather than “avoid goals”; “mastery goals” rather than “performance goals.”

In addition, he describes a “5S” approach for goals: simple, segmental, sequential, strategic, and supported, and takes a very long-term view towards getting results, building on small, achievable victories.

“The irony here is that ‘all or nothing’ doesn’t get us ‘all,’ it usually gets us ‘nothing.’ Which is why I like to practice ‘always something’ instead,” Berardi says.

The point here isn’t that Berardi, the DPP investigators, or anyone else has figured out some magic formula for driving behavior change. Rather, the takeaway is that motivating behavior change is extremely difficult, and seems to represent a critically important health promoting capability that is both desperately needed and difficult to locate anywhere in our health system. Most doctors lack the training, time, and perhaps forbearance needed to guide patients effectively down this difficult route.

This has created an opportunity for someone – maybe a profession, maybe a company – to step into this gap.

Hurdles Ahead

Three hurdles await:

- Driving durable healthy behavior change is intrinsically a wicked problem to solve.

- The business model needs to work. Someone has to pay for the cost of driving the healthy behavior change. It’s a real challenge given the historically low probability of success, and the need to tangibly (and credibly, as Quizzify’s Al Lewis unfailingly points out) realize the financial benefits of improved health – often in a relatively (perhaps unrealistically) short time frame.

- While technology offers the promise of scale, the power of health coaching seems closely tied to the close, trusted relationship and understanding that develops over time between coach and participant; while in theory, technology might offer the possibility of even more nuanced understanding and richer data collection, the power and intimacy of the personal relationship remains difficult to translate at scale.

This is the grand behavioral change challenge that brave health professionals, entrepreneurs, and technologists must now tackle, and upon which our collective health and well-being may depend.