New Book Contemplates How Generative AI Will Serve Man

David Shaywitz

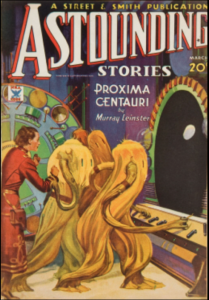

In 1935, Astounding Science — the premier science fiction magazine of the day, and perhaps ever — published “Proxima Centauri.” It was a short story envisioning an encounter between a voyaging earth spacecraft and a ship from a nearby star system.

Written by Murray Leinster (William Fitzgerald Jenkins), the tale features the original use of the phrase “first contact” in science fiction. Think Close Encounters of the Third Kind, or perhaps more appropriately the “To Serve Man” episode of The Twilight Zone, since Leinster’s aliens turn out to be carnivorous plants who quickly develop (as alien plants often do) a taste for human flesh.

“First contact” is also the phrase Microsoft’s head of research Peter Lee selects to describe his initial encounter with GPT-4, in The AI Revolution in Medicine: GPT-4 and Beyond, the engaging and timely new book he’s co-authored with Harvard physician-scientist and

AI researcher Zak Kohane and journalist Carey Goldberg, documenting the trio’s early experience with this emerging, intriguing technology.

Lee’s phrase seems apt. When I asked GPT-4 to provide the first paragraph of a blog post on the subject, written in the style of The New Yorker, it responded:

The phrase “first contact” conjures up images of flying saucers and green men, of awe and wonder, of fear and loathing. It is the ultimate fantasy—or nightmare—of humanity’s encounter with the alien Other. But what if the Other is not from another planet, but from another machine? What if the first contact we are about to make is not with a distant civilization, but with a new form of artificial intelligence that surpasses our own in linguistic prowess and creativity? This is the prospect that looms over us as we await the arrival of GPT-4, the latest and most advanced iteration of a technology that can generate coherent and convincing texts on any topic, given only a few words or sentences as input….

GPT-4 even provides a cogent opinion on the popularity of “first contact” stories in science fiction, suggesting it may reflect the interplay of curiosity, fear, hope, and imagination.

Lee and Kohane have worked on AI their entire careers – yet neither seemed prepared for their encounter with GPT-4. Both described losing sleep as they contemplated the implications of what they describe as an “alien intelligence” with whom they each formed a “relationship.” Both are struck by its capabilities,yet acknowledge its limitations.

Lee describes GPT-4 as “at once both smarter and dumber than any person you’ve ever met.” He is particularly captivated by its ability to “imagine emotions and perhaps even empathize with people.”

Lee and his colleagues also present a series of specific, formalized challenges to GPT-4, examining its common-sense understanding, its moral judgement, and even its ability to navigate “theory of the mind” tests, exploring GPT-4’s ability to intuit what others might be thinking. The performance of the technology was extraordinary, Lee reports.

Responding to one question involving two roommates who shared a cat that was moved from one place to another when one roommate left the apartment, GPT-4 not only correctly anticipated the likely reaction of each roommate, but even offered an opinion on what the cat in the scenario might be thinking – namely that the two roommates were “very rude and confusing because they keep moving it from one place to another without asking.”

As discussed in my last column, Kohane was especially impressed by the GPT-4’s clinical reasoning skills, and by the way it approached complex medical cases and suggested reasonable next steps. On the other hand, GPT-4 would also make some fairly basic mistakes (especially involving math), and would often confidently assert it was correct even when it demonstrably was not.

Having established GPT-4’s bona fides, Lee, Kohane, and Goldberg devote the balance of their text to a question that even the technology itself might struggle with: how do you solve a problem like GPT-4? Each of the three authors seems focused on slightly different aspects of the challenge.

Lee appears especially preoccupied with the underlying existential question of what GPT-4 is, and whether at some level it can “understand” and “empathize.” He seems consumed by GPT-4’s capabilities, particularly since so many of these, “were not programmed by humans. Instead, they emerged into existence – sometimes unexpectedly – as its neural network grew.”

He continues, “how on earth can it be that the next-word prediction can possibly do… all the things that we’ve seen…unfortunately, we simply do not know the answer to this question.”

Kohane seems hopeful the technology can be used as a partner or co-pilot for healthcare providers, reducing burnout, administrative burden, and medical error, while allowing providers to practice at the top of their license. He delights in the possibility of physicians able to focus once more on the complex reasoning and human relationships that had first attracted so many of us to the profession.

Carey Goldberg

Projecting forward, Kohane imagines a next-generation large language model, fancifully called “Dr. One-With-Everything,” encompassing “protein structure, other basic biological databases (like gene regulation and human genetic variation), preclinical studies, and the design and conduct of clinical trials.”

This model, Kohane suggests, “will be likely the central intellectual tool for biomedical research by the mid-2030’s.”

Goldberg, meanwhile, offers the most pragmatic and in some sense relatable perspective on how GPT-4 will be used. She recognizes that “because GPT-4 appears to be such an extraordinary tool for mining humanity’s store of medical information, there’s no question members of the public will want to use it that way – a lot.”

Already, Goldberg writes:

“health-related web searches are second only to porn searches, by some counts. Surveys find roughly three-quarters of American adults look for health information online. It’s not hard to predict a massive migration from WebMD and old-style search to new large language models that let patients have a back-and forth for as long as they want with an AI that can analyze personal medical information and seems almost medically omniscient.”

Moreover, she adds, patients want this capability now. While awaiting access to GPT-4, she writes, “My ‘everypatient’ emotion has tended to be impatience. Sure, I get the risks of hallucinations and other little-understood distortion, but I’ve still felt mainly the AI-delay frustration of people on the waiting list for chatGPT: ‘I get it – it’s not perfect. I’ll manage – just give me access!’”

The promise of democratizing this powerful technology is easy to appreciate. As Microsoft AI expert Karmel Allison tells Goldberg, “If the internet and the mobile age were about putting information in the hands of everyone across the planet, the AI age is about putting intelligence into the hands of everyone across the planet.”

Karmel Allison

At the same time, the co-authors all recognize that there are clearly risks involved in deploying this powerful technology. Kohane, for example, asserts “GPT-4 cannot be used in medical settings without direct human supervision.”

Kohane and Goldberg also suggest that this is the “moment for broad, thoughtful consideration of how to ensure maximal safety and also maximal access,” and emphasize the need for “guardrails to keep patients as safe as possible.” But they also recognize it’s a “tricky balance,” adding:

“those safety measures must not mean that the great advantages that we document in this book end up unavailable to many who could benefit from them. One of the most exciting aspects of this moment is that the new AI could accelerate healthcare in a direction that is better for patients, all patients, and for providers as well — if they have access.”

None of the co-authors seem to seriously contemplate pausing ongoing work in generative AI – as Elon Musk and others have recently proposed.

Kevin Scott

Collectively, the authors’ perspective seems well-summarized by Microsoft Chief Technology Officer Kevin Scott, who tells Goldberg, “The technology will exist. It will have an enormous amount of possibility. I think it will be incredibly useful and powerful. And then society has to choose how it’s going to use it.”

It’s a thrilling future to envision, to anticipate, and (as many of us hope) to help create.

Unless, of course, the technology breaks away, and chooses how it’s going to use us.

How To Serve Man? It was a cookbook.