Longevity Is Having A Moment

David Shaywitz

Dying, with few exceptions, has never been especially popular, and our shared interest in not dying hardly constitutes breaking news. Nevertheless, the aspiration of living longer — and remaining healthier while doing it — appears to be all the rage.

Consider these recent headlines:

- “Why is longevity sudden so hot?” – Chrissy Farr, Second Opinion.

- “The longevity business is booming – and its scientist are clashing” – Amy Dockser Marcus, The Wall Street Journal.

- “Rise of the superhuman” – cover story, The Economist.

- “The business of promoting longevity and healthspan” – Dr. Eric Topol, Ground Truths.

There have also been a slew of longevity-focused books over the last several years; Outlive, by Dr. Peter Attia, is perhaps the best known, and has spent over ninety weeks on the New York Times Bestsellers list. Also relevant: Dr. Howard Luks’s Longevity…Simplified: Living A Longer, Healthier Life Shouldn’t Be Complicated.

What’s going on – what accounts for this apparent surge of interest?

To oversimplify, there are two general (and not entirely distinct) lines of work that seem to account for this.

First, there’s the biological study of longevity itself – what accounts for the intrinsic limits of lifespan, and how might this be extended? Much of this biology, as Dockser Marcus describes in the WSJ, originated from studies in the Guarente Lab at MIT, and has been pursued by researchers including David Sinclair (now Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School) and Brian Kennedy (former CEO of Buck Institute for Aging, currently Distinguished Professor in Biochemistry and Physiology at the National University of Singapore).

Leonard Gaurente, Novartis professor of biology, MIT

Similar to many frontier areas, the underlying science of aging has proved particularly challenging. As Dr. Eric Verdin, CEO and president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Novato, California told Dockser Marcus,

“…the more you study something, the more you understand the complexity. There is no magic pill—even though we all would love the idea that there’s going to be something magical that solves all of your problems and prevents you from aging.”

The second area of work involves the factors that cause us to get sick and frail when we age. Attia describes four “chronic diseases of aging,” which he calls “the Four Horsemen”:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Cancer

- Neurodegenerative disease

- Type 2 diabetes and associated metabolic conditions

Dr. Attia’s framework, shared by others, is that each of these diseases develops very slowly over time, yet we tend to intervene only relatively late in the process.

The “goal should be to act as early as possible,” Dr. Attia argues. “We should be proactive instead of reactive in our approach. Changing that mindset must be the first step in attacking slow death.”

There also appears to be a shared belief that a key factor contributing to all four Horsemen (to various degrees) is metabolic dysfunction – essentially the idea that through excessive and unhealthy eating, and insufficient exercise, we develop insulin resistance, and our bodies enter a generalized pro-inflammatory state.

This contributes not only to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, but (at least to some extent) to cancer and neurodegeneration as well. Through focusing early on improved diet and more exercise, and monitoring progress closely, the hope is that we might delay, perhaps for many years, the arrival of the Horsemen.

Acting Without RCTs

One common attribute of many (but not all) researchers and entrepreneurs focused on either the biology of longevity or the prevention of chronic disease (or both) is a sense that action is required and warranted before definitive proof (in the form of randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of medical science) has been documented.

For example, Dockser Marcus writes,

Dismissing promising results because they aren’t definitive isn’t fair, Guarente said: “It is moving in the direction where there will be stronger and stronger data, maybe not in everything, but in some significant human health areas in the future.”

Similarly, Attia argues (in a section titled “From evidence based to evidence informed”) that while the “purists of evidence-based medicine demand data from RCTs before doing anything (emphasis in original),” the study of longevity isn’t particularly amenable to tradition RCTs because “it would take too long to do the study” and “the interventions are very complex, particularly if they involve exercise, nutrition, and sleep.”

Thus, he says, rather than wait for definitive proof that might never come, he argues we should extrapolate aggressively and thoughtfully from what we know, and recognize we’ll not achieve “absolute certainty,” but rather it’s about managing risk.

He argues we should think about approaching our health like an investment strategy, “seeking the tactics, based on what we know now, to deliver a better-than-average return on our capital, while operating within our own tolerance of risk.”

With this context, we can appreciate the rationale underlying both the consumer longevity companies (generally focused on extensive testing) profiled in depth by Dr. Topol and the supplements promoted by some of the longevity biologists interviewed by Dockser Marcus. Many longevity biologists are also working on developing what they hope will be FDA-approved medicines to combat aging.

We can also start to appreciate some of the critical dynamics associated with the surge in interest in longevity. If you believe traditional medicine is either excessively conservative about assessing risk or insufficiently proactive, or both, and if you are sufficiently well-off to afford the additional testing, then longevity companies are here to serve you.

On the other hand, Dr. Topol observes, “As is the case with the companies attempting to reverse aging, the ones marketing longevity, healthspan and advanced prevention to consumers have not yet provided any evidence for benefit.”

He continues,

That is not to say the concept behind these companies— a much broader collection of data— is wrong. My contention is that it is flawed because it is indiscriminate as to who undergoes testing and what tests (such as total body MRI or multi-cancer early detection) and when they are performed.

As Dr. Topol points out, according to Bayes Theorem, “if the pre-test probability is low, the accuracy of the test is substantially reduced.”

In short, the testing approach utilized by many longevity companies seems likely to generate a plethora of false positives, as well as additional testing, procedures, and anxiety. That’s a key concern for both physicians and payers — that we’ll run all these tests and waste a lot of time and money searching for problems that aren’t really there, and potentially generating new, iatrogenic problems in the process.

(Dr. Zak Kohane and colleagues described the challenge of “incidentalomas” in 2006, here; I’ve recently reviewed a book about Bayes Theorem for the WSJ here; the topic is also covered in another book I recently reviewed for the WSJ – Sir David Spiegelhalter’s The Art of Uncertainty – here.)

While today’s consumer-focused longevity companies focus on testing, the research around longevity science, while complex, as Dr. Verdin noted, remains exciting and promising. The work could ultimately lead to FDA-approved medicines capable of resetting our intrinsic rate of aging and significantly increasing our potential lifespan.

Alignment Around Lifestyle

Despite differences in thresholds for various diagnostic tests, there seems to be remarkable alignment around lifestyle interventions that can promote longevity. As Dr. Luks nicely summarizes (recommendations with which Attia and others seem to largely agree), key elements include:

Dr. Howard Luks, author, “Longevity… Simplified”

- Get and stay lean (now far more achievable thanks to GLP-1 medicines); eat real food.

- Move often, and ensure you engage in aerobic, muscle strengthening, and balance-promoting activities.

- Get sleep.

- Socialize.

- Have a sense of purpose.

As longtime TR readers recognize, I’m especially impressed by the impact of exercise, and I’m hardly the only one. As Attia writes, “The data demonstrating the effectiveness of exercise on lifespan are as close to irrefutable as one can find in all human biology.”

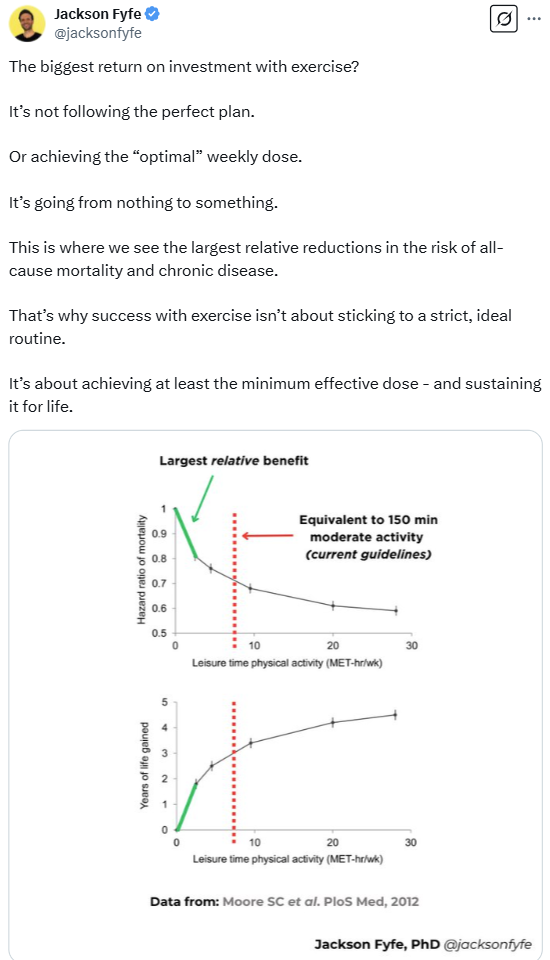

The disproportional impact of getting the sedentary to move even a little (as I’ve discussed here) is striking:

I am especially attracted to the idea of a healthspan platform that’s rooted less in arcane laboratory testing, and more in promoting a combination of activity and agency (which I suspect GLP-1RA medicines can help propel), particularly among the motivated tech-savvy highly agentic 50+ generation I’ve referred to as “The Vanguard.”

Bottom Line

Longevity is having a moment, driven both by decades of research into the biology of aging and by research suggesting metabolic dysfunction leading to chronic inflammation may contribute to major diseases of aging, exerting a deleterious effect over a very long time. The hope is that earlier intervention (perhaps prompted by a suggestive value on a laboratory test or imaging study) could mitigate the damage. One concern is that if testing is performed without consideration of pre-test probabilities, many false positives will be identified and pursued. On the other hand, GLP-1 medicines provide a profound opportunity, particularly when combined with suitable physical activity, for individuals to significantly enhance their years of healthy life. In addition, with continued research, longevity science may one day deliver FDA-approved medicines capable of significantly increasing intrinsic human lifespan.