Corporate Health and Wellness Has New Urgency And Vision

David Shaywitz

Like no other event in our collective experience, the pandemic reminded us of the need for an integrative view of wellbeing beyond traditional measures of physical health. Focusing exclusively on cholesterol level and bone density, for example, would be hopelessly inadequate for the needs of today.

I continued to be haunted by Zak Kohane’s description of the many children’s hospitals across the country that have stopped admitting patients for elective procedures.

This isn’t because the hospitals are overrun with COVID, Kohane says. Rather, the beds are filled to capacity with children whose mental health, exacerbated by the challenges of childhood in the era of COVID, now requires in-patient care.

Many employers have apparently recognized the urgent health crisis. “Workplaces went through an accelerated digital disruption” as a consequence of the pandemic, Forbes columnist Brian Solis writes. Corporate health and wellness offerings that used to be the sole provenance of HR are now getting the attention of senior leadership, talent management expert Josh Bersin explains.

Particularly in the face of “the great resignation,” when many employees are seriously rethinking their priorities and commitments, keeping workers happy and physically healthy has become a top business priority. The pandemic didn’t create today’s holistic view of employee health and wellness, but it dramatically accelerated and intensified employer interest.

Today, let’s take a quick look at the evolution of workplace health and wellness, consider the dimensions of health and wellness that executives are now contemplating, and assess how well these efforts are likely to perform.

Evolution of Corporate Health and Wellness

The introduction of health and wellness to the workforce is generally traced to the 1950s, HR expert Cheryl Brown Merriwether explains. Early efforts tended to focus on “industrial hygiene” – monitoring “air quality and cafeteria sanitation.”

In the 1970s, she explains, as the cost of healthcare assumed by companies climbed, employers looked to reduce these costs by promoting healthier lifestyles.

The first “modern” corporate wellness program is generally considered to be J&J’s “Live for Life.” The effort launched in 1978 with two goals: encouraging healthy employees by promoting healthy behaviors, and reducing healthcare costs for the company.

As Merriwether outlines, “Live for Life” was an onsite wellness program that

“included physical assessments, questionnaires, and provided employees with information on stress management, nutrition, and weight control. The program also provided support for high-risk behaviors such as alcohol or substance abuse.”

Corporate wellness programs began to incorporate psychological wellbeing in the 1980s. Around that time, workplace fitness programs, sometimes including onsite fitness centers, became more widespread.

In the 1990s, the US Department of Health and Human Services advanced an initiative called Healthy People 2000, which encouraged employers to promote healthy behaviors. “It was widely believed during this period,” Merriwether says, “that workplace health and wellness initiatives benefited both employees and company, even though evidence and supporting data were hard to find.”

The deliberate focus on creating and fostering a positive corporate culture, which started to gain traction during 1990s, took off during the tech-fueled 2000s.

As Bersin explains,

“In 2007, Google created a course on mindfulness that was an overnight sensation. It was the most popular benefit on the Google campus and sparked the trend toward mindful thinking at work, in design, and even in engineering. We believe many of the new ideas about growth mindset, abundance mentality, yoga, and various other philosophies of growth prominent today stemmed from this root.”

Companies continued to look to health and wellness programs for healthcare cost-savings. Through the 2010s, companies increasingly searched for ways to persuade employees to avail themselves of perennially underutilized wellness services, and thereby unlock the (always elusive – see here) cost savings.

Corporate wellness programs continued to evolve in the 2010s. As Abraham and White describe in Health Affairs in 2017, there was a transformation in value proposition, from “return on investment (ROI)” to the more expansive concept of “value on investment (VOI).”

As the authors explain, this means looking “beyond individually focused metrics of medical care cost savings or productivity gains,” and extending the scope “to include organizationally focused metrics such as employee engagement, turnover, retention, and satisfaction and even profitability.”

One health plan executive told Abraham and White that for employers, health and wellness may still be about healthcare costs, but it’s also increasingly about recruiting and retaining the most talented workers they can find. “It is way beyond ROI,” they say.

To address this need – a need obviously intensified by the pandemic – companies are creating “wellbeing care teams,” Merriwether reports. These teams are (or will be) staffed by “professional practitioners, both clinical and non-clinical, she says,” and “will include mental, behavioral, and integrative health practitioners working in partnership with health, wellness, and professional recovery coaches.”

Merriwether points out that the “market for health coaching services is $7B and growing,” and notes “there are currently more than 128,000 health coaches and educators who help clients establish lifestyle behavior changes.” (See here for my recent discussion of health coaches and technology.)

Components of Health and Well Being

For some time, as Bersin notes, most companies have embraced a view of “wellbeing as a constellation of social, mental, physical, and behavioral health.” However, Bersin adds, over the last decade – particularly “as work has become ever more focused on always-on digital tools” – new dimensions have emerged: “sleep and rest, meaning and purpose, relationships with others, and even positive thinking.”

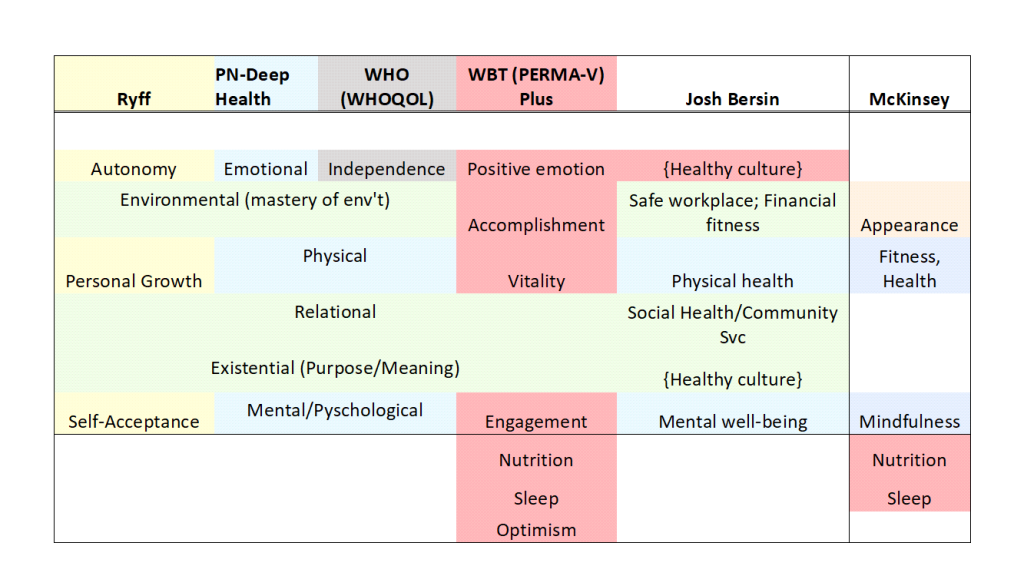

Bersin proposed a corporate health and wellbeing framework that includes six dimensions (plus enabling tech and HR capabilities); I’ve mapped this (imperfectly) onto the well being frameworks I’ve previously discussed (see here), and have also included a related but distinct set of six dimensions that McKinsey uses to categorize consumer interest in wellness.

Still Needed: Focus On Social Milieu

Today, Bersin points out, “nearly all companies have programs for resilience, wellbeing, mental health or stress reductions. Company leaders are adding new vacation policies, giving people apps and relaxation tools, and lavishing wellbeing benefits on their teams.”

So are these efforts working? If by “working” we mean creating a “healthy organization,” Bersin argues, then the answer is “no.” What’s needed, he says, is more than just “a set of benefits and wellbeing programs.”

Instead, he contends, what’s needed is “a top-down focus on job and work design, management, and rewards practices, a sense of psychological safety and fairness, and a commitment to listening to employees.”

What I think Bersin is getting at is a point that academic experts including Michael Kelly and Mary Barker have addressed as well: many well-intentioned “intuitive” solutions come up short because they fail to recognize and account for the complex social milieu from which behaviors originate.

In their instantly classic 2016 paper, “Why is changing health-related behavior so difficult?” Kelly and Baker highlight the failure of commonly-invoked approaches to behavior change. Among the examples they cite: “use common sense,” “it’s about messaging,” and “it’s about providing people with information.” They also explain why we can’t reliably be guided either by the assumption that “people act rationally” or by the view that “people act irrationally.”

What’s needed, they argue, is a view (called “social practice”) that “conceptualizes behavior not as something that can be reduced down to things that individuals do and think as if they were isolated from others.”

Kelly and Baker emphasize the importance of “disaggregating broad behaviors” (like eating, drinking, smoking, etc), “breaking them down in time and place where different expression of these behaviors occur.” And of course, they remind us, more research is required.

Key Takeaways

For executives who need to help employees today, and for health-oriented entrepreneurs looking for a way to contribute, there are several takeaways.

First, it’s tremendously exciting and hopeful to see so many offerings targeting the many dimensions of health and wellness, a Cambrian explosion that would seem to increase the chance for the development of truly high-value products. The diversity of wellness alternatives now available theoretically offers greater opportunity for individual employees to find programs that best meet their particular needs.

But there’s a downside to this burst of activity. The volume of offerings makes it hard for employees to navigate the system and make good choices. (Full disclosure: I’ve worked in several large corporations and never managed to successfully navigate a benefits systems, which always seemed incredibly complicated, and to involve a series of nested options and endless passwords.)

Apparently, I’m not alone. Bersin cites research that finds almost half of employees consider their multiple workplace wellness programs to be confusing. That’s a big roadblock that gets the way of using benefits.

What matters most when it comes to corporate wellbeing solutions, Bersin says, are “simplicity and transparency.”

Yet we should also not get so lost in the weeds of benefit deployment that we lose sight of what seems to be a really encouraging development – the increased recognition that our health and wellbeing is often closely tied to the environment we’re in: the nature of our work, the richness of our engagement with colleagues, the way in which our effort is recognized and valued. It’s also an area where genuine commitment and involvement by senior leaders can make a palpable difference.

Let’s dare to be hopeful for a moment. The increased availability of personalized corporate health and wellbeing options, from health coaches to fitness centers to mental health support, together with more integrative company-wide efforts that authentically promote and enable a healthy culture, offers exceptional promise.

We can begin to imagine what the future of work could, and arguably should, be.

Wellness, Not Woo Woo

One final point: it’s really important to recognize that the pursuit of wellness need not come at the price of hard work and exceptional performance.

Phrased differently, wellness doesn’t have to be “woo woo.”

As the father of positive psychology, University of Pennsylvania professor Martin Seligman takes pains to explain, the “A” in his PERMA-V model (a framework represented in column four of the previous table) represents “Achievement.”

Seligman further emphasizes that we feel best when we enter a state of complete absorption, termed “flow” by the late Mihaly Csikszentmihaly. We are most likely to experience “flow” when we are fully utilizing our core strengths. (Then again, when I took the test, my top three turned out to be “love,” “perspective,” and “curiosity,” so perhaps I should have become a rabbi.)

Flow may also explain why, as a recent WSJ article reported, entrepreneurs tend to be happier than wage-earning employees – even though entrepreneurs on average work longer, make less, and are more stressed. “All of those problems do take away from entrepreneurs’ happiness, of course,” the Journal acknowledges, “but the positives of running a business are so strong that they outweigh the negatives.”

The point: while it’s smart for companies to embrace health and wellness as a corporate value, it will be even smarter if leaders embrace and authentically support the remarkably diverse range of ways in which this worthy goal might be meaningfully pursued.