Biopharmas: Digitizing, But Not Quite Digital

David Shaywitz

What a difference two years makes.

In January 2020, I left my role as a senior partner at a corporate life-science venture fund to pursue my interest in what I recognized as a captivating frontier: the intersection of biopharma with emerging digital and data technology.

I set up an independent consultancy, and advised senior R&D executives in both large and small pharmas. The need to understand digital technologies profoundly intensified with the arrival of the pandemic – as my co-authors and I documented in this National Academy of Medicine-sponsored analysis published earlier this year.

Our family moved from the Bay Area back to Boston in the summer of 2021. After a decade developing infectious disease medicines at Gilead, my wife became CEO of Allovir, a Cambridge-based public biotech company – a profoundly exciting opportunity. In autumn of 2021, our three daughters – entering grades 7, 9, and 11 – each started the academic year in a new school.

And in March 2022, I returned to the pharma company I left two years prior, in what feels like a tailor-made role, VP-Distinguished R&D Fellow, Data and Digital. The ambition: “to realize the future of biopharma through the thoughtful and pragmatic integration of rigorous biomedical science and emerging digital and data technologies.”

It’s been…busy.

Returning to the same company (albeit a different location) after a two-year hiatus is providing an unusual before-and-after view into the organization and the industry more generally: a lot has happened, and so much is different.

Office life: the new normal

As so many of us have discovered, the office has radically changed. Most work is hybrid, and teams show up to the office several times a week (or less if someone is truly remote). Moreover, many organizations, including ours, have adopted a “hoteling” system meaning that you don’t have your own office, or even your own cubicle. In the morning, you plunk your stuff down at an available desk in your team’s designated “neighborhood,” and then you haul it away at the end of each day.

I’m not a huge fan of this approach; I like the idea of having a designated work area, which I can personalize; in my pre-pandemic life, I enjoyed stopping by my colleagues’ desks, seeing pictures of the families, knowing where to find them if I had a quick question. It contributed to my sense of belonging and the feeling of community. In contrast, I’m finding the flash-mob approach to office life less congenial – although our dog appreciates the extra attention he receives on the days I’m working from home.

Digital progress

Other changes I’ve noticed are surely for the better. Digital and data strategy has moved from the periphery of the organization to the core, as part of a CEO-driven digital transformation effort that seems to have really taken hold. There’s a sense of pragmatic possibility among the folks working on digital and data, driven by the palpable progress they’ve seen in a number of areas (like finally moving most compute from on-premise to the cloud, for example).

The organization has also recruited – and retained – exceptional talent, which seems especially encouraging given the demand for these skills.

These efforts occur in the context of an industry that (as I’ve written in this space in the context of Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Lilly) is clearly making efforts to embrace digital, while also coming to terms with the challenges.

At a high level, it seems like what’s happening across the industry is what Jeanne Ross and her co-authors of Designed for Digital describe as “digitization,” which they distinguish from the higher-order ambition to develop and deliver digital offerings.

As Ross and colleagues write:

“We distinguish these two potential impacts of digital technologies as the difference between digitized and digital. Digitizing with digital technologies involves enhancing business processes and operations with SMACIT [social, mobile, analytics, cloud, internet of things] and related technologies. For example, Internet of Things technologies can automate support of distributed equipment or operations; mobile computing can create a seamless employee experience; artificial intelligence can help automate repetitive administrative processes. The applications of digital technology can certainly benefit a company, but they digitize a company; they do not make it digital.”

The authors continue, “digitization enhances operational excellence; digital enhances the customer value proposition.” Digitization “is a prerequisite to digital transformation,” they argue, not equivalent to it.

This description of digitization seems like a perfect summary of what the industry is currently (and unevenly) attempting, an effort to improve operational efficiencies by leveraging the digital resources now available and routine in other industries.

Digital and COVID-19

As described by Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla in his captivating new book Moonshot, Pfizer’s ability to deliver a COVID-19 vaccine with such speed is attributable, at least in part, to an effort initiated prior to the pandemic to digitize operations. In the context of COVID-19, Bourla seems to have imbued the organization with a palpable, urgent, must-do culture (grounded on the premise that “time = lives”). By affording a common and up-to-date window into progress and problems, the digital dashboards enabled this culture by allowing the entire organization to align and focus.

(It should be noted that, as this insightful 2021 McKinsey analysis points out, most of the 10-fold acceleration in vaccine development observed during the pandemic likely reflects the combination of enhanced regulatory engagement and extraordinary at-risk investment. Even so, the operational efficiencies – enabled by digitization – were also important.)

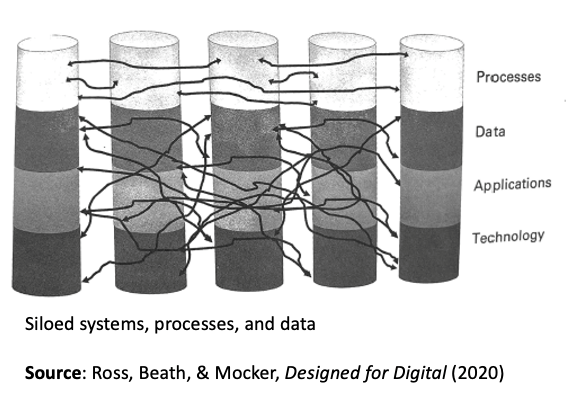

It will be interesting to see the extent to which biopharma can build on this success to further digitize, and rationalize/organize the many data flows within companies. Established biopharmas are notoriously siloed, as well as stitched together from years of successive acquisitions. This has a tendency to lead to kludged-together data solutions (see figure) that may get the job done, MacGyver-style, but are inefficient and result in missed learning opportunities.

In theory, digitally-native companies, such as Moderna, should start with an enormous advantage. The ability of Moderna – a young company that entered the pandemic a fraction the size of Pfizer – to develop and deliver a novel vaccine in record time speaks to promise of such a foundation, as Iansiti and Lakhani argue in Competing in the Age of AI.

Of course, it’s also easy to rationalize that COVID-19 was a special case, and that Moderna just happened to be in exactly the right spot at the right time.

Hence question one: can digitally-native biotechs consistently beat pharmas at their own game? Phrased differently, will the apparent operational efficiencies, and improved access to data (which can serve as the basis for further learnings, including those enabled by AI) enjoyed by digitally-native biotech companies represent a meaningful competitive advantage, or will experienced pharma giants manage, through selective digitization, to capture enough of the benefits to avoid disruption?

Question two, of course, is whether digitally-native biotechs – particularly those intent on building digital platforms – can potentially win at a different game, similar to how the iPhone beat Nokia; more on this later.

Lakhani, for his part, asserts that “traditional incumbent organizations have no choice but to embrace [a digital future]. Either you’re going to be competing against the platform or you’re going to be part of a platform that is going to be AI-first.”

Follow this space…

I am following progress in three areas with particular interest:

Future of evidence generation. This is a broad area that generally seeks a more complete understanding of and relationship with patient/participants, involving enhanced breadth (longitudinal data) and depth (e.g. wearables). It prioritizes both ease of participation (eg distributed/hybrid trials) and equity (diverse representation). For a phenomenal overview of this area by one of its leading lights, see this recent presentation by Dr. Amy Abernethy of Verily.

Getting beyond operational efficiency. Digital efforts to date in our industry and others have been most successful in the context of structured, high-volume data and repeatable activities. But in the big picture, what we need more than anything in biopharma are improved translational models – a way of figuring out if a molecule we put into people will actually work, and work safely. The failure rate of clinical development remains abysmal. While AI approaches are constantly hyped, the available data, as Andreas Bender eloquently discusses here, and as Derek Lowe has written here, appears to represent a poor fit for AI solutions.

Escalating security and privacy concerns. The potential insights associated with participant data are accompanied by profound responsibility for ensuring these data are managed appropriately, and always in accordance with the participant’s wishes; thus data stewardship has emerged as a critical pilar of all digital efforts. Add to this the increasing concerns related to bad actors. As FBI Director Robert Mueller said in 2012, “I am convinced that there are only two types of companies: those that have been hacked and those that will be. And even they are converging into one category: companies that have been hacked and will be hacked again.”

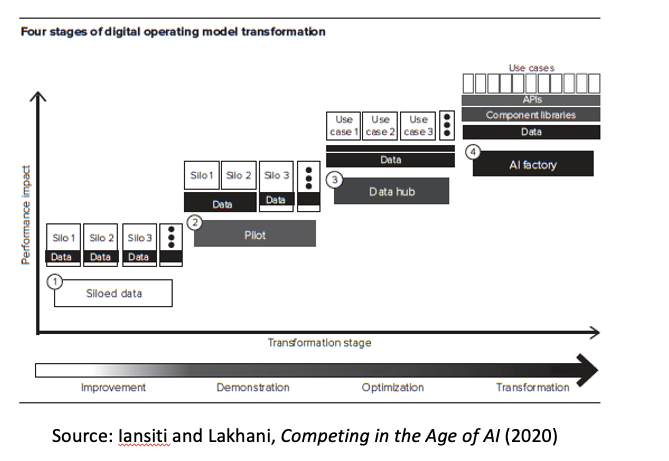

To these I might add a fourth topic, which could be called service-oriented architecture, but really boils down to the central premise of both the Ross book and the Iansiti and Lakhani book: will any biopharma embrace the radical digital transformation both sets of authors advocate, as captured in this figure:

The authors of both books emphasize the power of what they describe as a digital platform, constructed as shown at the right of the figure.

Here’s the basic idea: in traditional firms, as Iansiti and Lakhani write (slightly paraphrased), the

“organization, data, and technology evolve into silos, with disparate retail focus areas largely contained in separate, disconnected units. Connections between silos are haphazard and often unpredictable, motivated by meeting immediate needs and fighting fires.”

A better approach, the authors contend, is to adopt a “modular, distributed structure” based on “a common set of building blocks that could be deployed to drive scale and scope.” At the heart of this approach is a “central, standardized set of services” and the ability to easily communicate through interfaces known as APIs.

Consequently, “one of the seminal documents in the digital transformation of business,” according to Iansiti and Lakhani, might be a memo Jeff Bezos issued in 2002, in the early days of Amazon, mandating the use of this API-based approach throughout the company. While challenging to adopt, this approach is what ultimately enabled Amazon to scale so fast and so well.

In an industry that seems to be struggling even to digitize the information in narrow silos, such a transformation seems like a nearly impossibly heavy lift for established organizations. As Brian Bergstein has written in Technology Review, “the most common uses of AI have involved business processes that are siloed but nonetheless have abundant data.” Most work is happening within silos, not across them.

Most folks in pharma would love to do their existing jobs better, and struggle less to find and manage the data they currently need; but the idea of transforming the entire enterprise in hopes of facilitating the development of novel digital solutions may prove a prohibitively difficult sell, especially when their current objective – developing impactful new medicines — seems intrinsically worthy and consequential.

Besides, as Bergstein points out, the reports from the AI front are mixed, as “people in a wide range of industries say the technology is tricky to deploy. It can be costly. And the initial payoff is often modest.” While he notes that technologists may be most interested in “What can the technology do,” the key question for companies is “How much will we benefit from investing in it?”

Transformation visionaries like Ross, Lakhani and their co-authors might suggest another question: “How much will you lose by not investing in disruptive technologies?” And they might suggest we speak to the good folks who used to work at Kodak and Nokia for perspective.