Preserving the Biotech Social Contract – We Should All Be Pitching In

[Editor’s Note: This is a preface by Jeremy Levin supporting the following essay by Steve Potts.]

Biotech is an industrial tapestry woven together by remarkable people with deep intellect, determination, passion, and bravery all driven to create the next and best medicine.

Underpinning it is an immense and complex infrastructure including capital formation, regulatory processes, patient advocacy, policy making, health insurance, media and many other stakeholders. Together they make up the core of what has not just delivered hundreds of lifesaving medicines but positioned America as the preeminent producer of medicines in the world.

Biotech is a national strategic asset.

But to continue to be successful on this mission we need to take account of the evolving and increasingly complex social, political and economic environment we operate within.

It is no longer sufficient, appropriate or adequate to operate as if we still in the 1970’s of Milton Friedman. If we do, we will help undermine our industry. It is incumbent on participants in our industry to engage with all stakeholders, express our values publicly and encourage and seek the support of those we serve, the patients.

If we don’t, we risk allowing the fabric we have created, being torn asunder by policy makers and those that do not understand the contribution biotech makes to those tackling disease and disorders, their families, the economy and the nation. They will hear only a narrative which focuses on price and downplays the value of innovation and medicines. They won’t hear the voices articulating our social contact.

This approach and the commitment it takes from all of us, is not woke. It’s good business.

In his essay below, Steve Potts, a serial entrepreneur and CEO, makes a powerful statement on the role of stakeholder engagement and the importance of the social contract. He points out those that have stepped forward and how they have stepped forward. The list includes names of long recognized leaders and encouragingly, a new and more diverse generation of female and male biotech executives, including most recently, the biotech sisterhood. Steve’s voice should be listened to, his data are sobering, and his “ask” is both admirable and achievable. To those reading this, I echo his appeal: step forward.

—Dr. Jeremy Levin, chairman and CEO, Ovid Therapeutics

My Road

Steve Potts, oncology executive

Dr. Steve Potts – Anticipate Biosciences

Mountain biking is my weekend escape from the stress of drug development. The trails of Arizona provide a place to get some exercise, and to enjoy beautiful natural scenery.

Previous generations worked hard to build those trails that all of us can enjoy today. It’s our job to maintain them.

One recent Saturday, a few friends and I joined a work party to clear debris and fix some erosion damage, especially on tricky curves. Trail upkeep was needed after a long stretch of monsoon rains. Someone needed to do it, and my friends and I figured we should do our part. A few hours on a Saturday weren’t much to ask.

My friends, fellow biotech executives and investors, we have similar upkeep work to do. We’re fortunate to work in an industry that benefits from decades of investment and is now brimming with possibility to improve human health. But if we don’t do our part to maintain a healthy ecosystem, we’ll find ourselves on increasingly rocky, slippery, dead-end trails.

Creating a new therapeutic is like a long mountain climbing expedition. Maybe one in 50 ideas reach the base camp of a first-in-human milestone. From there, one in 10 (at best) reach the actual summit of FDA approval to become revenue-generating products. At least those are the odds in my area of oncology. Cancer is a tough mountain.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Biden, contains provisions intended to control drug prices, and curb the amount the federal government spends on them. There are reasons why the public has been outraged over drug prices for many years, and why elected officials felt compelled to respond to the outrage. But in crafting this policy, the government has created a toxic side effect for small molecule drug development. It is so severe that it could all but wash out a section of the oncology mountain. The IRA subjects all NDA-path drug candidates including small molecules, oligonucleotides, and peptides to price setting by Medicare merely nine years after they come to market.

Today, companies and their investors typically count on having 14 years[1] on the market before generic competitors erode the price and profits.

Nine years is far shorter than 14, especially when you consider that between the challenges of securing reimbursement and proving that the drug works in different stages of the disease, revenues take a while to ramp up. Truncating a drug’s marketability by five years can cut its profitability by half. By comparison, biologic drugs get 13 years before Medicare negotiation knocks their price down, which is close enough to 14 not to alter how we think about the reward for antibodies or other biologics.

Science wouldn’t necessarily lead us to a policy that prioritizes large molecules over small molecules. In both neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, etc.) and cancer brain metastases, small molecules are the weapon of choice over biologics because of their ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. If a biologic kills off all cancer cells in the body but cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, the cancer could come back lethally as brain metastases. We need both small molecule and biologic weapons in our toolkit.

The fix is straightforward: we need 13 years for small molecules, as we have for biologics, for investors to continue supporting this area.

It’s not like small molecules cost less to develop or are less risky to develop than biologics. Their development has simply been rendered much less rewarding to investors.

Survey Says

I have been fundraising for a Series A to support our clinical trials and have noticed a distinct change in investor attitudes toward small molecule drug development after the IRA was signed into law.

I’m a data-driven guy, so I conducted a survey online of nearly 100 biotech investors and CEOs. The results are deeply disturbing for the future of oncology drug development. Since the IRA’s passage, six of every seven investors have moved away from funding small-molecule drug development programs for the elderly because the nine-year negotiation clock for NDA-path medicines makes them unattractive investments.

I’ve been working in oncology for three decades. Conducting this survey was the first time I went to work to improve the hiking and biking trails of drug development. It struck me as necessary in the aftermath of the IRA monsoon, much like trail upkeep seemed necessary after the heavy rains hit Arizona.

As I spent a little volunteer time in trail management, I became more aware and appreciative of others who had spent years ahead of me on these trails. I also noticed how many biotech executives like me have taken the stability and the incentives of our industry ecosystem for granted. Many haven’t yet gotten involved but it’s starting to change. It must change.

The Many Tending the Trails

The nonprofit organization No Patient Left Behind has pulled our industry together in a type of trail maintenance. Many identify as Biotech Builders on the NPLB website in support of the biotech social contract.

The statement is simple and powerful: “People must be able to afford (through proper insurance) all appropriate treatments and all medicines must go generic without undue delay.”

That idea guides us to support reforms that lower out-of-pocket costs for patients, opposes patent gaming by companies, and opposes government price controls on new drugs.

The IRA caps individual out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 a year. That’s a positive change. The IRA is aligned with the biotech social contract in several important ways, except in its treatment of small molecule drugs.

I believe that no congressional leader seeks to do harm deliberately. Like all of us, they have aging family members who hope for better drugs for deadly diseases like Alzheimer’s and cancer. They need our feedback on how to ensure that new drug development expeditions are financed and that all patented medications either become generic or are priced as generics after patents expire.

Engaging in dialogue with policymakers is one form of trail maintenance. In the last two years, hundreds of executives and investors have written and signed letters to Congress trying to explain what it takes to keep biomedical innovation going, how it generates value for our society, and the advantages of insurance reform over price controls in achieving affordability without sacrificing progress.

Many people in our industry are rolling up their sleeves. From 2021 to 2023 five Letters to Washington posted on the No Patient Left Behind website[2] have attracted over 3,000 signatures from leading investors, biotech executives and employees, big biopharma companies, bankers, service providers, as well as researchers, patient advocates, and economists.

Some Investors Take a Stand, Many Stay on the Sidelines

In looking at who signed all these letters, it’s clear how active some investors have been in standing up for biomedical innovation.

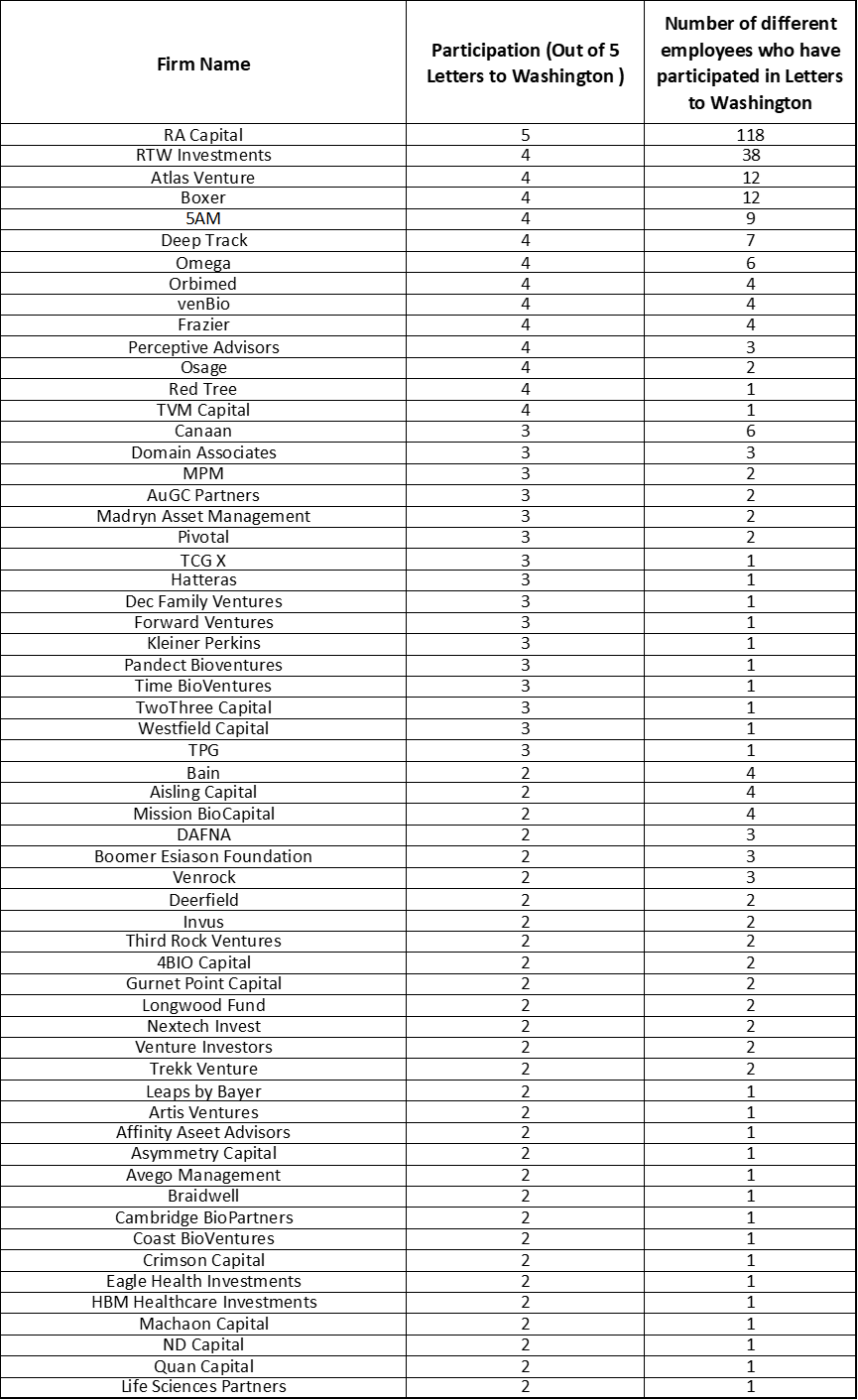

A total of 189 total venture funds are represented by the signatories across the five letters, shown in Table 1 ranked by the number of letters they signed and how many of their people participated.

Many VCs firms are quite small, so a few signatures may represent a notable fraction of a firm, or maybe everyone feels represented by the signature of a leader.

But it’s also notable how some firms inspired widespread participation among their employees, suggesting a clear commitment by their leaders to mentoring others on the importance of actively preserving the innovation ecosystem and tending to the trails. RA Capital, RTW Investments, Atlas, Boxer, 5AM, Deep Track, Omega, and others have done this, setting an inspiring leadership example for all of us.

And yet, I noticed that some firms were missing among the signers.

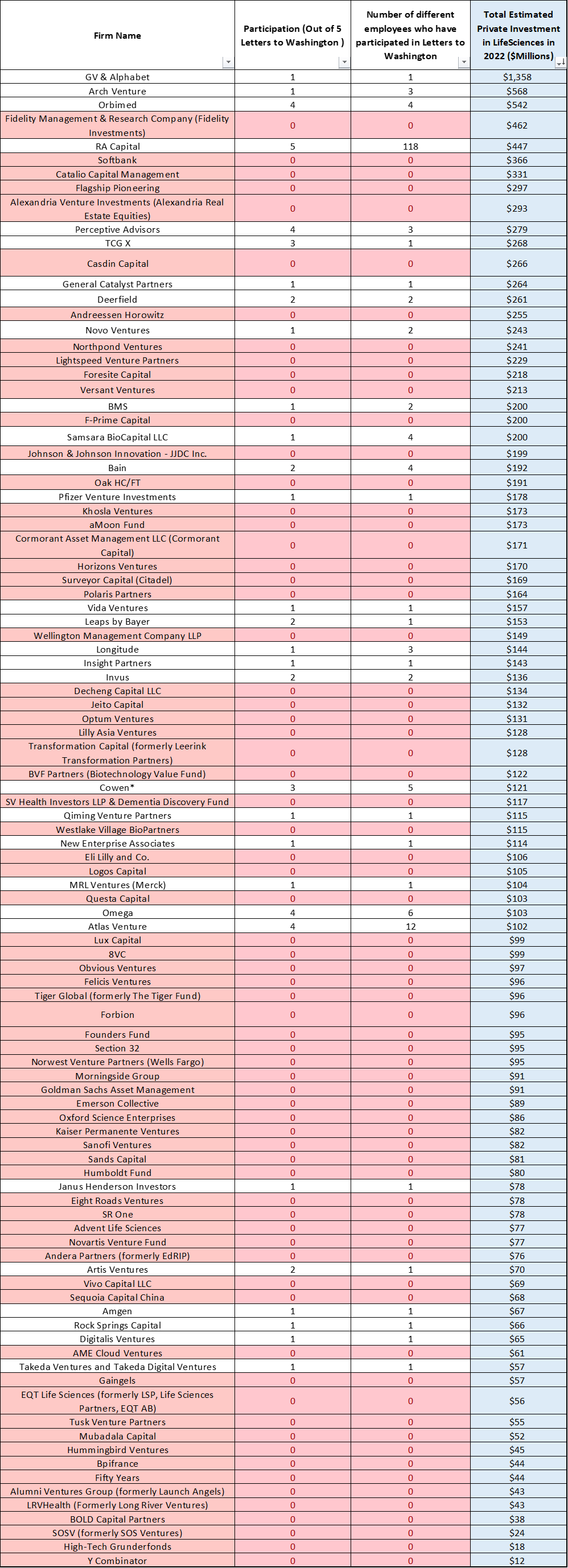

To get a sense of who was missing, I looked at which investment funds we normally think of as active in biotech (in this case based on how much each deployed into private financings in 2022, based on data from Endpoints) and cross-referenced them with the letter signers.

Table 2 shows that, disappointingly, 70 out of the top 100 did not sign a single letter despite how much they would seem to lose from biotech trails eroding.

Signing letters is not the only measure of how much someone cares to stand up for biomedical innovation (e.g. it was great to see Eli Lilly CEO Dave Ricks participate in an NPLB webinar on the harms of the IRA).

But, given the stakes and how easy it is to show support for a message by signing a letter, it’s telling when institutions repeatedly remain on the sidelines.

It’s not as though they don’t use the biotech trails. They are running the trails and supporting companies that run the trails. They just aren’t preserving them. That’s disheartening, because scaling the oncology mountain and developing treatments for other diseases is not just about profits for any of us.

Our ability to innovate could save the lives of the people who are closest to each of us. We all have a personal stake in keeping the biotech trails viable.

Support From All Quarters

Reviewing the lists of signers, I noticed other key contributors in our ecosystem took a stand. Commendable examples include the IR firm LifeSci Advisors (with an impressive 68 different employees represented among the signers), the investment banks Cowen and Bloom Burton, the CRO ICON. Also, Derek Lowe and Bruce Booth, two of our best biotech bards.

It would be great to see more participation from banks, service firms, and contract research organization partners, if not because of the personal impact of biomedical innovation for all their employees and their families then because their own businesses depend on the success of biotech R&D.

Big biopharmas were not much represented in the early letters, but the signatories of the latest letter (on the primacy of the FDA as the proper arbiter of which medicines should be on the market) attracted CEOs of giants like Pfizer and Biogen and executives from many other large companies. Their continued involvement is deeply appreciated by all of us small company executives.

The biotech social contract is under attack as never before. We can no longer take for granted that the trails for current and future drug development treks will remain fundable unless we all get involved.

Rod Wong, managing partner, chief investment officer, RTW Investments

Rod Wong of RTW said it well: “We should never take for granted the biotech ecosystem we have in the United States. No other place has this kind of biotech ecosystem. If we do take this for granted, one… the world will be worse off, because so much of biotech innovation happens here, or two… the US will lose its leadership position.”[3]

If you are considering getting involved, don’t wait to be asked. Sign up with NPLB as a First Responder so that you hear about these initiatives and follow people like Peter Kolchinsky, Jeremy Levin, Laura Shawver, Paul Hastings, John Maraganore, and no doubt many others who tweet about these initiatives so there is no chance that you miss another grassroots action. Talk to your Representatives and Senators in your home state. Protecting healthcare innovation is a truly bipartisan challenge.

The IRA’s treatment of NDA-path drugs is causing more than a monsoon’s worth of damage to our trails; it could leave entire swaths of the oncology mountain untraversable.

As we make plans and gather teams for new biotech expeditions, we will deliberately seek to partner with investors who share our love for the biotech social contract and who spend the time to teach others in their firms to contribute to societal good in this way. It’s essential to maintain the trails established by previous generations.

Let us all be part of this work.

[1] How do we get to 14? Patents last 20 years, but a lot of that patent life is eaten up by the drug development process. Up to five years of patent life can be restored via the Hatch-Waxman Act, a decades-old law designed to both incentivize drug development and create a thriving generics market.

[2] There are four letters written to the public and Congress and one meant to align industry around the importance of fixing the IRA. Four letters are about the IRA and one recent one was about the importance of preserving the FDA’s standing as the scientific arbiter of which medicines can be on the market.

[3] Minute 18 of this video.