Science in the Face of Fear: Vaccine Hesitancy and Public Trust

Larry Corey, MD

This month has been a media whipsaw.

News of the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines’ compelling efficacy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s rapid response and issuance of an Emergency Use Authorization for both vaccines have been met with equal parts jubilation and fear from a divided public.

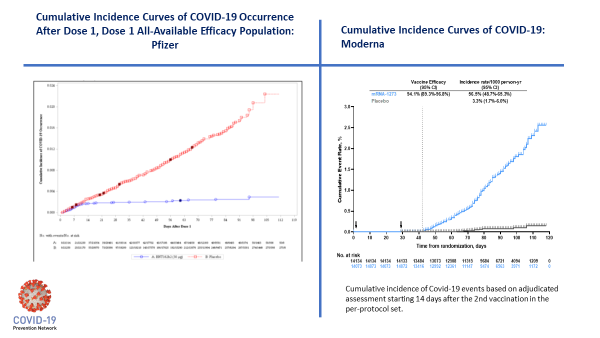

For me, as a medical virologist and researcher, this remarkable achievement is a clear demonstration of the power of science and its potential impact to save lives. To see these curves below that show the difference in disease course between those vaccinated and those receiving the saltwater placebo are about as big a spread as I’ve ever seen in any study.

We call these Kaplan-Meier curves, and if you’ve worked in cancer or most diseases, you just never get to see curves like these. Even when a study is considered a success, rarely do you see evidence this overwhelming in favor of a new drug or vaccine. And this is one reason I have embedded the curves of both studies into this blog. If you are used to seeing these curves, they just make you smile and think, “How did that happen?”

A scientific success such as this one just feels good. With it comes a sense of community pride, particularly when you see the incredible adulation from impassioned medical care workers who are grateful to receive the vaccines. It’s wonderful to see videos of them dancing outside of the hospitals. We as scientists have to smile when we see images of front-line workers with their heads bent, overcome with relief and gratitude for a vaccine that seems powerful enough to relieve them of the stress of dying on the job.

And yet, we can’t quite fully celebrate now. How does one measure a successful outcome in its entirety when recent polls show that approximately 40% of Americans would be unlikely to get a vaccine even when it becomes available to them? Or when one reads about town hall meetings populated by fellow Americans who are clearly mistrustful, images with hesitant faces. The fear is plain.

These images and data force one to pause—to take a step back and view the difference in perspectives—because the two visions side by side are difficult to balance.

True, maybe many Americans haven’t seen a Kaplan-Meier curve before. Maybe they don’t understand the nuances of the clinical studies and their protocols. But they understand what 95% protection from disease means—a clear indication the vaccine means it helps; it helps a lot.

Even so, I see the fear firsthand. An acquaintance of mine recently told me his mother refuses to take the vaccine. She is over the age of 70, and has multiple risk factors for severe COVID-19. This woman has sought my advice for other medical concerns, so she clearly has some measure of trust and respect in my opinion. But in this situation, the fear overrides her knowledge of what science can (and does) accomplish.

My first reaction was to talk to my acquaintance in an authoritative way, wearing my medical science hat, so to speak. Then it occurred to me that I wasn’t going to change her worldview simply because I was “the medical authority” sharing the information.

So, then I tried to step back and ask myself a few questions. How can I do this respectfully? Or how much energy should I put into this? How do we set our expectations? What’s the goal here? I’m reminded of one of those statements learned by most of us early on—probably while arguing with an authority figure who was trying to offer reason: you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.

So, I think there are lessons to be learned on both sides—that we all need to be respectful of differing viewpoints while we move toward greater understanding, compassion, and trust. And we all need to understand that there is context—for each person.

There are some situations—and the COVID-19 pandemic might be one of them—where the tincture of time is needed to heal the wounds. And there are wounds that have bred mistrust: wounds caused by self-serving narratives of national leadership that were unrelated to the scientific process at hand. And although the outgoing administration did a wonderful thing by providing an enormous amount of funding, “Operation Warp Speed” isn’t a name that inspires trust.

In most other contexts, and certainly outside of a public health emergency, when we think of the rigors of science, speed is not something we associate with positive outcomes. As one old proverb goes “haste makes waste.” Even those who don’t subscribe to that folk wisdom might naturally wonder, “were corners cut along the way to get a result this good, this fast?”

As someone on the inside I can say unequivocally – no, corners weren’t cut. Rigor was maintained. Yet I can see why people might still be suspicious. Throughout the vaccine trials, anytime something good happened, credit was narcissistically claimed by the President rather than letting the real inventors own it. By personalizing it, the vaccines became politicized. It created an odd discord, as if science—and what is in a vial—had something to do with whether you’re a Republican or Democrat.

Of course, we didn’t put Democrats in the vial; we didn’t put Republicans in the vial. It’s true: we had a lot of political leaders take control in an unscientific way and try to dictate the human behavior they wanted to see. But the scientific goal has always been: how do we alter and stop the disease that was rapidly attacking our nation and its people? How do we use pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical interventions alike to control the spread and keep Americans safe?

Scientifically, the goal has always been the same. How different political leaders communicate varies. And the vial gets caught up in the middle.

I don’t know how to unwind this except for time. I don’t know how to unwind this except for understanding.

My brother-in-law, a role model who inspired me to become a physician, passed on a wise saying when I was young. He died far too early, at age 37, from Candida sepsis that struck him while getting treatment for Hodgkin’s disease. Before he died, he said to me, “Larry, the educated man is the tolerant man.”

It will take work by all of us—in the scientific community and in the broader public. It will take hard work to convey the importance of vaccination. It will take time to rebuild trust across the divide. And it will take a public open to healing discourse; a public which remains curious and eager to know more as we learn more. Because we will.

If this pandemic has taught us anything, it has taught us that scientific successes beyond imagining are possible with resources, urgent focus, and the kind of global scientific collaboration we’ve seen over the past ten months. And as a scientist and physician, I will take solace in knowing that those who want the vaccine and can benefit from it, will be able to get access to it.

I pray that all who want, not just in our country but globally, will be able to receive this gift of science. All the people of the world deserve to be vaccinated. It is a great feat to say, with clear conviction, “COVID-19 is a vaccine-preventable disease.”

Dr. Larry Corey is the leader of the COVID-19 Prevention Network (CoVPN ) Operations Center, which was formed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health to respond to the global pandemic and the Chair of the ACTIV COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Trials Working Group. He is a Professor of Medicine and Virology at University of Washington and a Professor in the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division and past President and Director of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.