Vaccine Scarcity: Buckle Up for Debate

Larry Corey, MD

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are likely to secure Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) from the FDA by Christmas.

These are amazing gifts of science. They also arrive with high expectations from a weary public, especially since the clinical trials of these mRNA vaccines indicate near-complete protection from severe disease.

These first two vaccines arrive at the most tumultuous time yet in the pandemic. We are seeing a surge of people being newly diagnosed with COVID-19 across the country. More than 90,000 people are now hospitalized, and our healthcare capacity is being stretched to the limits. The death rate, after months of decline, is now heading back up. The upheaval in our daily lives has been with us for nine solid months. This terrible set of circumstances should help push back against the vaccine hesitancy we have heard about from public opinion polls.

The desire for protection from this sinister virus ought to prevail, and lead to a successful national vaccination campaign in the months ahead.

The demand for a vaccine is clear. Unfortunately, however, the demand for these vaccines will markedly outstrip their supply, at least for the next four to five months. That seems like an eternity, especially with the rate of community spread we are now seeing. Vaccine scarcity will be in the news for the next several months until one or two other types of vaccines — beyond the initial batch of mRNA vaccines — can meet the safety and efficacy requirements for an EUA distribution and become widely available.

How did we get into this predicament — where science came up with a couple of exceptional vaccines, but we can’t deliver them to everyone?

The pace of vaccine development has been unbelievably quick; quicker than anyone ever expected. This remarkable scientific accomplishment has outstripped the existing manufacturing supply chain. The conceptual framework of a victory against the virus exists, but in order to proclaim victory, we need mass vaccine manufacturing distribution and uptake.

Making and distributing vaccines is a complex process. There are many steps, and each step requires detailed quality control measures to ensure that each and every vial contains the right dose and right substance. To think of it in a more personalized way, what goes into every arm — including yours and mine — needs to meet manufacturing standards. That is not an easy task and one that takes specialized facilities and highly trained personnel, more than currently exist.

It’s especially difficult when you recognize that mRNA vaccines are an altogether new type of platform for vaccine development. Never before have they been manufactured at the scale of millions — even billions — of doses.

When we look at the number of doses being made versus what we need, it’s a daunting thought. Between Pfizer and Moderna, we expect only 20 million doses to be available in December; 30 to 40 million in January and February; and 60 million per month in March and April. Even if we reach 200 million doses, that’s only 100 million people vaccinated at best — less than half the U.S. adult population.

As I’ll describe below, these doses may not even cover the populations we feel most need the vaccine.

So, who’s in line for this scarce resource and who decides who gets vaccinated first? We knew that vaccine scarcity would be inevitable since the beginning of the Operation Warp Speed (OWS) program. Independent groups and other experts have been evaluating all along how to define and develop an equitable national vaccine access strategy.

The National Academy of Medicine, or NAM, the country’s premier independent group of scientists and medical policy makers, was commissioned by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and OWS to evaluate this issue.

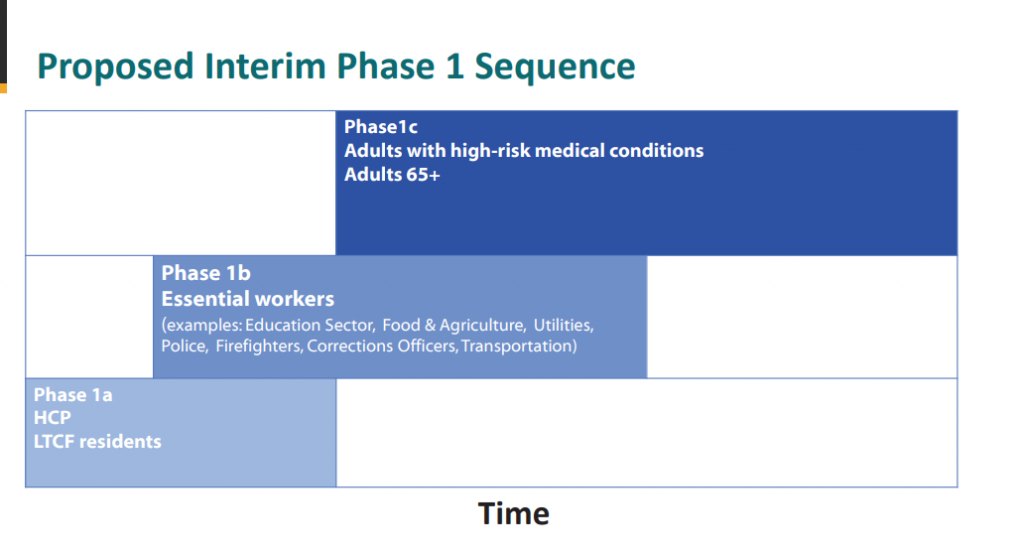

NAM divided access to effective vaccines into four categories and estimated the number of people in each of these categories. As shown in the first phase (1A and 1B), they prioritized health care workers and the elderly in high-density communities, such as nursing homes, followed by the elderly that have comorbidities like autoimmune disease or diabetes, which raise their risk of severe COVID-19. The NAM panel classified essential workers as the second group.

In both phases of distribution, the panel emphasized that economically disadvantaged communities must be given equal access in all situations.

The second group of experts enlisted was the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). That’s the CDC’s arm that makes recommendations for public health authorities around the country. The ACIP is the committee that has defined populations recommended for vaccination for over 50 years. Its advice is linked to public health–funded programs and defines insurance coverage for vaccines.

This group has been discussing who ought to get the COVID-19 vaccines first for many weeks in open meetings. It has, in its first rendition noted below, suggested that essential workers and first responders and medical personnel be in the first group.

Essential workers comprise group 1B, for example grocery store workers and meat packers. The third priority group (1C) is the elderly and those people with comorbidities. These 3 groups of people alone comprise well over 150 million people.

That all adds up to a lot of vulnerable people – more than we can vaccinate right away. Estimates are we’ll have enough vaccine supply for about 90 million people by April 2021.

How does one handle this scarcity when a case for vaccination exists for a very large segment of our adult population?

ACIP Proposal

How does one choose between a healthy frontline essential worker with no comorbidities — someone with a lower risk of death but a higher chance of becoming exposed and infecting others — than an elderly person with comorbidities who has a much higher risk of death but could perhaps self-protect more by limiting exposure?

Is there a right answer to who gets vaccinated first or do we have to understand and practice principles of equity and patience until we have enough vaccine for everyone?

Both groups — the National Academy of Medicine and the ACIP — are advisory. They make recommendations to the public and executive branches of state governments. We have national-guidelines, but we don’t have a nationally controlled distribution plan.

Each state will make its own choice about allocation. We will see differences in distribution by locale. Understanding and communicating these differences to the public will be challenging. Some will call it confusing.

I’m sure there will be some disagreement, some of it loud and angry, about who should get the vaccine when.

One principle should be upheld; we should use every available vial. Nothing should get wasted.

The only real solution to overcome vaccine scarcity is, of course, to remove scarcity, which means that the remaining vaccines need to be made available. So, the AstraZeneca vaccine that you’ve heard about, which reports about 70% effectiveness; the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine still being tested in a blinded pivotal clinical trial and others, will need to pass scientific muster and then be made widely available as well.

We are hopeful that answers on how these vaccines perform in the U.S. will be known by late January 2021 — less than two months from today.

For the time being, we’re going to have to get used to this issue of vaccine scarcity. However difficult it may be, we will have to be patient, and conscientious of broader societal needs, at least until more manufacturing capacity for the mRNA vaccines exists, or more likely, other types of vaccines become available for all of us.

Dr. Larry Corey is an internationally renowned expert in virology, immunology, and vaccine development and a leader of the COVID-19 Prevention Network (CoVPN), which was formed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health to respond to the global pandemic. He is a Professor of Medicine and Virology at University of Washington and a Professor in the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division and past President and Director of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.