George Yancopoulos, That Rarest Of Species – A Physician-Scientist Still In Charge Of A Pharma

David Shaywitz

Growing up in an academic household (my parents are both professors at Yale Medical School, still engaged, as ever, in dyslexia research), it was perhaps inevitable that, outside of my parents, my first role model was the brilliant President of Yale University, the late Bart Giamatti (you know- Paul’s dad).

The elder Giamatti inspired me so much as a teenager (his wife was my favorite high-school English teacher), I borrowed an excerpt from his wonderful “Earthly Use Of A Liberal Education” address as one of my high school yearbook quotes. It was right next to quotes from Watson, Crick, and Monod, lifted from Horace Freeland Judson’s magisterial history of early molecular biology, The Eighth Day Of Creation.

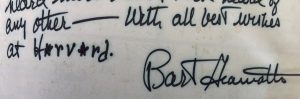

Bart Giamatti signature in David Shaywitz’s high school yearbook.

In college, as I pursued laboratory research in immunology, I first became familiar with the work of another intellectual superstar, who also became a role model — in this case, inspiring not only me, but also an entire industry: George Yancopoulos. When I was interviewing for MD/PhD programs in 1988-89, one of the highlights of the process was the chance to meet Yancopoulos (who I think was still a legendary postdoc in Fred Alt’s lab at Columbia University, though Yancopoulos may have stepped up to the faculty by that time). It was probably a smart decision not to go there to work with him (I had opted for Boston), because he shortly decamped in 1989 to become scientific founder of a tiny startup Leonard Schleifer had founded the year before. It was called Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

I should say that I’ve never worked directly for Regeneron – the closest I came was when I joined DNAnexus as chief medical officer, and had the opportunity to participate in the early days of the Regeneron Genetics Center, for which DNAnexus was (and, I think, still is) providing key aspects of the cloud data infrastructure and analytics. It was DNAnexus’s participation in this project that played a key role in attracting me to the startup, and the project proved even more exciting than I could have ever anticipated.

I was thinking about Yancopoulos yet again this week while reading a Wall Street Journal article about emerging medicines in the pipeline for COVID-19. It was a characteristically well-reported Journal article, discussing projects from many companies, but Yancopoulos was, shall we say, not underrepresented in the proceedings. While other companies seem to have shared updates in the usual ultra-cautious how-are-the-media-going-to-screw-pharma-this-time kind of way, with Yancopoulos, you could feel his personal passion for the science jump off the page. It was a sense aided and abetted by screenshots of critical internal communication (photo credit: George Yancopoulos) and of a happy team celebrating a research milestone (photo credit: George Yancopoulos).

It was the sort of enthusiasm and evangelism (don’t get him started on the “magic mice”) you might expect from a startup founder. Which, of course, he is. His brilliance, and unmistakable enthusiasm, for the science shines through in every interaction he has – with partners, investors, employees, and even with the media. (Listen to him on The Long Run podcast, October 2017.)

Maybe the best way to appreciate the distinct respect Yancopoulos has earned from me and so many others in the biopharmaceutical industry is to consider the contrast between leading tech companies and top pharmas. Many of the top tech companies are – or were, until recently — led by their engineer-founders: Zuckerberg at Facebook, Bezos at Amazon, Brin and Page at Google, Gates at Microsoft. Even after the founders departed, most top tech companies continued to be helmed by card-carrying engineers – Nadella at Microsoft, Pichai at Google, for example. (As for Apple – well, good luck figuring out what box Steve Jobs belongs in – or Tim Cook, for that matter.)

But move over to Big Pharma, and you see an entirely different set of individuals in the C-suite. You see no founders — understandable because in most cases, the companies were launched many years ago. But you rarely see physicians or scientists as CEOs or Presidents. Big pharmas are led instead by adept corporate managers. To be sure, each of these companies has internal R&D, yet they have all become increasingly reliant on innovation that occurs elsewhere in the startup ecosystem, and which the big companies must someday pay a premium to acquire.

Even more to the point, business success in biopharmaceuticals would seem to depend less on the understanding of medicine and science, and more on the ability to manage massive corporate structures. The thinking of investors is clearly that sophisticated corporate mangers can deliver shareholder value in a way that physicians and scientists generally cannot. Perhaps this is also why pharma doesn’t see a lot of acquihires – startups acquired just for the talent. In biopharma, intellectual property is the coin of the realm.

In tech, great software engineers are seen as likely to create something valuable time after time. There’s even a term in Silicon Valley around ‘10X’ engineers who some believe are worth 10x the average engineer and therefore must be aggressively recruited and earnestly retained. While experienced drug hunters are valued, you just don’t see same kind of human resources attitude in biopharma that you see in tech. Drug discovery is such a capricious and uncertain business that while you can certainly do it conspicuously badly, it’s hard to be consistently successful – too much seems beyond anyone’s control. The key job of pharma executives is figuring out how to keep a biopharmaceutical company going despite the inability to count on any specific research initiative leading anywhere. As I’ve discussed, this is a key challenge of running a “miracle-based business.”

Which brings us back to Regeneron and Yancopoulos. It’s true Yancopoulos is technically not the CEO (that’s Schleifer’s job) – Yancopoulos is the President, head of R&D, and a member of the board of directors. The head of R&D is a position that exists at all biopharma companies and is generally staffed by distinguished scientific leaders like Mathai Mammen at Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, Hal Barron at GSK, and Roger Perlmutter at Merck. In practice, Yancopoulos has even more clout in his organization – he has the authority of the co-founder and President he is.

The fact that a savvy physician-scientist is in charge shows. The company, now valued around $55B, behaves like a science-driven startup, with priorities set almost exclusively by internal research. While most of the pharma industry has embraced Joy’s Law – no matter who you are, most of the smartest people work somewhere else – Yancopoulos doesn’t behave like he believes this; he thinks he can lead the best biopharmaceutical drug discovery team in the world, and that this represents the company’s unfair advantage. (It has also attracted criticism from others in the industry who see this as hubris, and not very long ago questioned the company’s capability in late clinical development and effective commercialization; I’m not sure where Regeneron stands in these essential areas today.)

In some ways, I look at Yancopoulos the way you might have looked at the first molecularly-targeted oncology medicine, Novartis’ imatinib (Gleevec), from almost 20 years ago. Gleevec is an example that’s held up as representative of biomedical science, yet which turned out – at least for a while – to be far more the exception than the rule. As a physician-scientist with a passion for making medicines, I look at Yancopoulos as accomplishing what I and so many doctors and researchers hope to achieve. He has managed to take his personal passion for driving science into application and turn this into a successful, science-driven company that he continues to lead and drive, goad and inspire.

The question is why aren’t there more large companies like Regeneron, with more leaders like Yancopoulos? (Vertex may be another example.) Perhaps if Yancopoulos continues to lead the company to further achievements, there will be. In the same way ambitious engineers may be attracted to an organization built by Zuckerberg or led by Pichai, physicians and scientists would unquestionably gravitate to successful drug development organizations that hadn’t descended into corporate doublespeak, endless committees, and matrix management, but rather were informed by the scientific vision and founder’s passion – biopharma companies that were doing outstanding science and consistently winning because of it. Many eager researchers seek these qualities in startups – but imagine how wonderful it would be if you could find such a stimulating, challenging environment in an organization with enough resources to drive this vision forward through commercialization at scale.

Hopefully, this model will become more common – I would love to see the industry more beholden to medical science than to management “science,” and led by physicians who know what it’s like to take care of sick patients, and scientists who are daring, yet humble, because they fully appreciate the complexities of human biology.

But until then, at least we have Yancopoulos, continuing to run his company and speak his mind, in a spirit perhaps best evoked by Frank Sinatra:

Yes, there were times, I’m sure you knew

When I bit off more than I could chew

But through it all, when there was doubt

I ate it up and spit it out

I faced it all and I stood tall

And did it my way