Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

15

Dec

2025

Biotech’s Future Will Be More Distributed

John Flavin, founder and CEO, Portal Innovations

When we started our first biotech company, MediChem Life Sciences in the early 1990s in Chicago, there was nothing resembling a “biotech ecosystem” nearby.

We had to build our own labs, figure out how to raise money and how to recruit a team of scientists and professionals. The universities in the Chicago area were more focused on basic science. The culture frowned on connections between faculty and industry.

The scene has changed dramatically.

Pat Flavin, president, Portal Innovations

Although still early in development, the Chicago biotech ecosystem is thriving. A similar story is playing out around the U.S. and internationally.

Academic research has undergone a shift over the past decade, driven by the need for practical application in the life sciences. Federal funding for research has flattened, and universities have sought new ways to attract and retain talent. One way to attract bright young scientists is by fostering an environment conducive to translational research and embracing the sort of relationships with industry that were once frowned upon.

The result is that life science entrepreneurship and new product development is flourishing outside traditional coastal epicenters, creating a dynamic and distributed map of regional hubs across the United States. This article explores the impact of the emergence of these life sciences innovation hubs around the world, examining how these ecosystems are reshaping the future of biomedical innovation.

The Changing Dynamics of Research Funding

Historically, research universities relied on federal grants to fund cutting-edge research aimed at discovering new drugs, devices, and diagnostics. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget, for instance, peaked in real purchasing terms at approximately $41.7 billion in 2022, but projections show a stagnation or slight decline because of federal budget cuts and inflation eating away at the purchasing power of NIH-funded scientists.

This reduction in basic science activity, exacerbated by the current U.S. administration’s threats to slash more dramatically, has prompted research institutions to rethink their business models.

Today, there is a growing emphasis on translational research—research that aims to transform scientific discoveries into practical applications that benefit society. The market is huge and growing. The global biotechnology market is expected to reach $2.4 trillion by 2028, according to a report by the Milken Institute.

COVID Disruptions That Are Here to Stay

The Covid-19 pandemic acted as a global shock to the life sciences innovation system, accelerating pre-existing trends and forcing a rapid re-evaluation of how and where innovation happens.

Before the pandemic, innovation was firmly concentrated in established hubs like Boston/Cambridge and the San Francisco Bay Area. The pandemic didn’t kill these centers of innovation; it further established their importance as hubs with spokes that are delivering new energy to the nodes in the network.

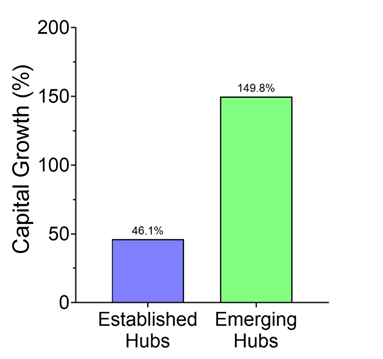

Figure 1. Capital growth shift in venture ecosystems. Percentage change in total invested capital comparing the post-COVID era (2022–2025) to the COVID-era baseline (2018–2021) for companies receiving a 1st Round deal between $2–15M. Emerging Hubs (150%) experienced higher relative capital growth than Established Hubs (46%) during this period transition.

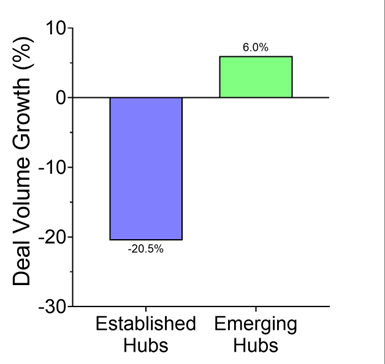

Figure 2. Deal volume shift in venture ecosystems. Percentage change in the total number of deals comparing the post-COVID era (2022–2025) to the COVID-era baseline (2018–2021) for companies receiving a 1st Round deal between $2–15M. Deal volume contracted by 20.5% in Established Hubs but grew by 6% in Emerging Hubs, highlighting a structural shift in deal flow.

The post-COVID era (2022–2025) was compared to the COVID-era baseline (2018–2021) for companies on Pitchbook raising a 1st Round deal between $2–15M. Established hubs are defined as companies in MA and CA. Emerging hubs encompass companies in GA, IL, NJ, RI, and TX.

Investing in Homegrown Scientific Talent

Regional biotech hubs must attract and retain innovative faculty and researchers to be competitive. Younger academics are prioritizing the impact of their work beyond traditional publishing in peer-reviewed journals. A survey by the American Association of Universities found more than 70% of new faculty members now consider industry partnerships and translational research opportunities when choosing an institution.

Regions that effectively create and promote an environment conducive to innovation are reaping the benefits. Cities like Boston, San Francisco, and San Diego have become magnets for scientific and entrepreneurial talent because of their established biotech ecosystems. For example, the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council reported that Massachusetts is home to over 1,000 biotech companies, employing more than 60,000 people and generating over $5 billion in annual revenue.

Until recently, talented researchers who got their training outside of the leading biotech clusters were exported along with adjacent intellectual property to the established biotech hubs. The top hubs are like suns – they have a strong gravitational pull. This made sense because these researchers and their ideas needed to be plugged into a rich environment full of local investors, CEOs, CMOs, pharma companies, and other partners.

This export phenomenon is changing. Most top-tier research institutions and the regions they anchor are actively investing in the environment to retain the talent they have attracted. This investible talent migration is making it possible to start and scale companies in new geographies.

For example:

Nathan Gianneschi, professor, Northwestern University; co-founder, Grove Biopharma

- Nathan Gianneschi was recruited by Northwestern University for his work at the intersection of materials science, medicinal chemistry and synthetic biology. He launched Grove Biopharma in Chicago at Portal with his colleagues Paul Bertin and Geoff Duyk in 2021. The company closed a $30m series A earlier this year and are working on protein-like-polymers targeting protein-protein interactions.

- Sarah Hein got her Ph.D. at Baylor College of Medicine and partnered with professors Max Mamonkin and Malcolm Brenner to start March Biosciences in 2022 which has raised over $50 million including CPRIT funding and recently reported exciting preliminary data on their CD5-targeted CAR-T cell therapy for T-cell lymphoma. They decided to build their company in Houston at Portal.

Sarah Hein, co-founder and CEO, March Biosciences

- UChicago recruited Ray Moellering to support his research in chemical biology. He started ReAx with seed funding from AbbVie Ventures, Portal and OMX to develop tools that manipulate protein structure, function and signaling to develop drugs addressing previously undruggable targets.

The pandemic was a significant contributing factor. It accelerated the remote work revolution. The experience proved that not every part of R&D needs to be in a physical hub. The geographic location of life sciences innovation has become more fluid and [we believe] the future of life sciences innovation will be less about a single best location and more about the strength of the network connecting diverse and specialized geographic nodes.

Regional Advantages and Success Stories

Different regions have different advantages. For example, Kendall Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is renowned for its concentration of biotech firms and research institutions. The proximity of prestigious universities, such as Harvard and MIT, creates a vibrant ecosystem that attracts talent and investment. According to a report by CB Insights, over $8.1 billion was invested in Boston-area biotech companies in 2020 alone.

Similarly, states like Texas, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Washington, and North Carolina are investing heavily in infrastructure and workforce development programs. For example, North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park, home to more than 300 biotech companies, has generated more than $4.9 billion in revenue and supports over 60,000 jobs. Texas taxpayers approved and renewed the Cancer Research and Prevention Institute (CPRIT) $6 billion that invests directly in biotech companies in the Lone Star State.

Texas built on the CPRIT success by investing in a new $3 billion fund this year focused on neurodegenerative diseases. It’s called the Dementia Research and Prevention Institute of Texas (DPRIT).

David Baker, professor of biochemistry, University of Washington; director, Institute for Protein Design

Washington state hasn’t directed state resources on the same level, but its community is playing to its own strengths. Nobel laureate David Baker, a Seattle native, has attracted brilliant colleagues at the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington. This core group of scientists, in turn, is supported by a network of local investors and entrepreneurs, including the Gates Foundation.

Great science attracts investors, corporate partners, graduate students and young faculty. All of this activity builds momentum and critical mass for the local biotech ecosystem.

Case Study: The University of Chicago and the Polsky Center

The University of Chicago’s Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, in our home region, exemplifies how academic institutions are adapting to the changing landscape. After years of building the center, it has become a pivotal player in fostering entrepreneurship within the university. The center has facilitated the launch of more than 160 startups since its inception, attracting more than $1.3 billion in funding.

The center’s transparent approach to innovation has led to successful partnerships with industry, allowing researchers to access funding and resources necessary to bring their ideas to market. Hyde Park Labs, Harper Court Ventures, GS Innovation Fund and the Polsky Center focus on providing faculty with tools to start ventures with market-worthy platforms. This model serves as a blueprint for other universities aiming to establish their own biotech hubs.

These activities have spawned biomedical spinoffs including:

Tom Gajewski, professor, University of Chicago

- Pyxis Oncology was founded on Tom Gajewski’s seminal work in understanding how T cells interact with the tumor microenvironment. Pyxis went public in 2021 and is pursuing novel treatments for hard-to-treat cancers by targeting the tumor microenvironment with its lead ADC asset in clinical studies.

- Onchilles Pharma is leveraging Lev Becker’s research identifies altered macrophage signaling and protein expression across different disease contexts. Their efforts aim to translate these mechanistic insights into new therapeutics. The Company recently raised a $40 million series A to fund clinical proof of concept studies for its lead asset.

- ClostraBio founded on research from Jeff Hubbell’s and Cathy Nagler’s labs recently launched a commercial probiotic with a novel butyrate producing strain for gut health.

Creating a Local Market

Providing an option for innovators to start their ventures locally increases talent and company retention. It’s not enough for a university to support translational research and entrepreneurial support to spin out a company. These early-stage ventures need access to a broader market of investors and partners. Without a local market, these companies migrate to established hubs.

By facilitating collaborations between researchers and entrepreneurs, our platform at Portal provides a local market in young biotech ecosystems by providing seed capital, lab space and talent to build and scale locally.

Prior to Portal’s launch in 2020, local seed capital and commercial lab space did not exist. Scientific cofounder Ryan Clark returned home from working at Sana in Boston along with University of Illinois Professor Brad Merrill. They wanted to build their company in Chicago to access strong synthetic biology talent. Syntax Bio, a CRISPR-based cell therapy startup spun out of UIC launched in 2021 at Portal, received funding from Portal and DCVC Bio, and recently partnered with Astellas, Illumina and Draper for their Series A round.

Connecting the Hubs

Young ecosystems can’t survive sustainably over time in isolation. Connected innovation hubs are crucial for the success of the local markets. Kendall Square thrives with transparency and momentum since all the dots are connected. Simulating this environment across a wider geography is possible by connecting all the nodes. These hubs facilitate talent flow, collaboration, knowledge sharing, and resource exchange among various stakeholders, including researchers, entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers. The concept of “three currencies”—economic, intellectual, and social capital—underscores the importance of building robust networks within these ecosystems.

As biotech hubs continue to grow, they pave the way for new opportunities. The ability to connect researchers with industry leaders and provide access to resources is vital for driving innovation and addressing global health challenges.

Chicago has a cluster of talent and infrastructure around high performance computing and quantum fueled by Argonne National Laboratory. Ecosystems with research groups and start-ups around the world working on data intensive biology efforts such as RNA applications access these resources through collaborations.

Global Trends in Biotech Innovation

The rise of biotech hubs is not confined to the United States. There are several interconnected factors have powered the rise of hubs outside the US.

Seeing the success of the US life sciences industry, foreign governments have highlighted biotech as a strategic priority for economic growth. Forward-looking governments are applying successful incentive programs including grants and R&D tax credits. In addition, a growing spirit of collaboration between regulatory agencies has improved the streamlining of regulatory pathways to accelerate drug approvals.

Instead of trying to replicate the broad model of Boston, new hubs have achieved success by applying a specific niche strategy of focusing on the regional strengths. Some key examples of this niche strategy: Switzerland excels in biologics and large molecule therapeutics. Ireland and Israel are leaders in medical devices and the UK is a world leader in genomics and AI-driven drug discovery.

Around the globe, countries such as China, Japan, the United Kingdom, Israel, and Australia are emerging as leaders in biotech innovation. Saudi Arabia, UAE and Greece are picking up the pace. For instance, China’s biotech market is projected to reach $173 billion by 2025, driven by substantial government investments and a rapidly growing demand for healthcare.

Similarly, the UK’s focus on collaboration between universities and industry has resulted in a thriving biotech sector, with the UK biotech industry contributing £84 billion to the economy in 2021 and supporting over 280,000 jobs.

The Future is Distributed

The rise of biotech hubs represents a significant shift in the landscape of academic research and innovation. As universities adapt to changing funding dynamics and prioritize translational research, the potential for impactful discoveries is greater than ever. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, attracting innovative talent, and investing in infrastructure, regions around the world are seeking to capture some of the benefits of the biotech revolution. New ecosystems open possibilities for new types of innovation and novel business models leveraging the endogenous strengths of the local market. Fusing tech platforms such as quantum, AI, and advanced batteries in to life sciences may be more likely in new places with different people than the established centers.

Some of the biggest ideas of the future may come from places off the beaten path. New ecosystems tend to attract more risk takers since the price of failure is higher. But the rewards to innovators, investors and patients can be substantial. Over time, as these ecosystems scale, the risk factor decreases.

Sources

Federal Funding Trends:

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Budget:

National Institutes of Health. (2022). NIH Budget Fact Sheet. Retrieved from NIH https://report.nih.gov/nihdatabook/category/1

Global Biotechnology Market Growth:

Milken Institute. (2021). The Global Biotechnology Market: A $2.4 Trillion Opportunity. Retrieved from Milken Institute

University Faculty Trends:

American Association of Universities. (2021). New Faculty Survey: Trends in Research and Industry Partnerships. Retrieved from AAU

Massachusetts Biotech Employment:

Massachusetts Biotechnology Council. (2020). 2020 Massachusetts Life Sciences Industry Report. Retrieved from MassBio

Interdisciplinary Research Collaboration:

Nature Biotechnology. (2018). The Importance of Interdisciplinary Research. Retrieved from Nature

University of California San Diego Infrastructure Investment:

University of California San Diego. (2021). UC San Diego Invests $1 Billion in Research Facilities. Retrieved from UCSD News Center

Boston Biotech Investment:

CB Insights. (2021). 2020 Boston Biotech Report: Funding Trends and Insights. Retrieved from CB Insights

North Carolina Research Triangle Park:

North Carolina Biotechnology Center. (2021). The Economic Impact of the North Carolina Biotechnology Industry. Retrieved from NC Biotech Center

University of Chicago Polsky Center:

University of Chicago Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation. (2022). Impact Report. Retrieved from Polsky Center

Global Biotech Startup Funding:

PitchBook. (2021). 2021 Global State of Venture Capital Report. Retrieved from PitchBook

China’s Biotech Market Growth Projection:

China National Pharmaceutical Industry Information Center. (2021). China’s Biotech Market Report (in Chinese). Retrieved from CNPIC

UK Biotech Industry Economic Contribution:

BioIndustry Association. (2021). The UK Bioeconomy: A £84 billion Opportunity. Retrieved from BIA