Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

16

Apr

2024

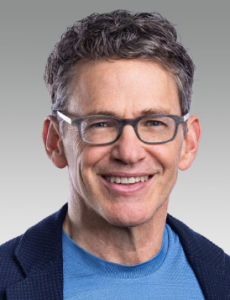

New Tools & Techniques for Biology: David Liu on The Long Run

David Liu, professor, chemistry and chemical biology, Harvard University; core institute member, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT

Today’s guest on The Long Run is David Liu.

David is a professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Harvard University, and a core institute member at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. In biotech industry world, he’s a founder or co-founder of a long list of companies, including Beam Therapeutics, Prime Medicine, Editas Medicine, Chroma Medicine, and Exo Therapeutics. And that’s not the entire list.

His best-known contributions to industry include a first-generation CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing company, a CRISPR base editing company, then a prime editing company, and epigenetic editing company. But there’s a small molecule drug developer taking aim at unconventional binding sites on enzymes.

One common thread that runs through David’s career is a focus on using new tools, and developing new techniques, to advance biology. Besides the widely known advances in gene editing, he’s known for fundamental work on phage-assisted continuous evolution and DNA‐Templated Organic Synthesis that set the stage for his later work. Going back and reading some of those early papers sheds some light on what and why he did the things that came later.

In this conversation, I asked David to talk about his early life and influences that maybe aren’t so widely known among collaborators in academia and industry. We spent a good bit of time on that, before getting into more recent advances with base editing and prime editing.

This conversation was recorded Apr. 2 in his office at the Broad Institute.

Before we get started, I have a couple of announcements to make:

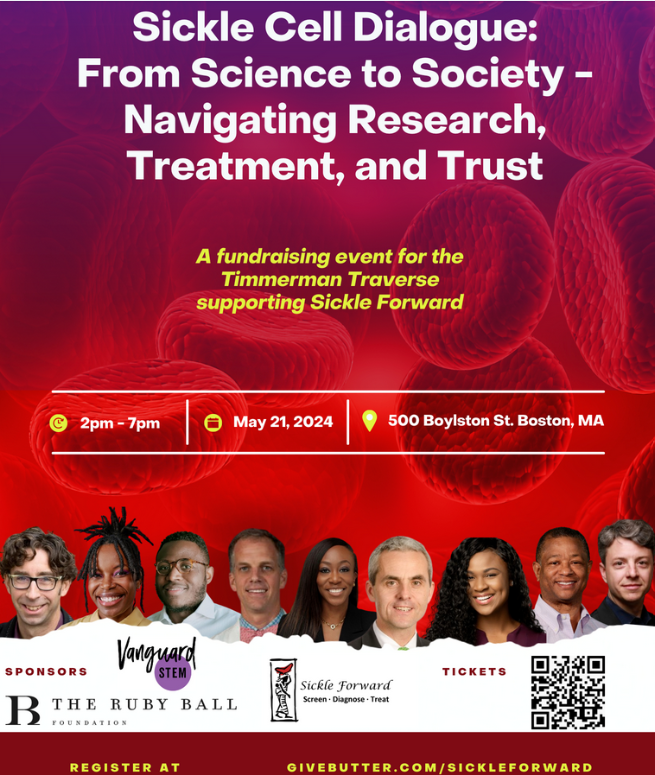

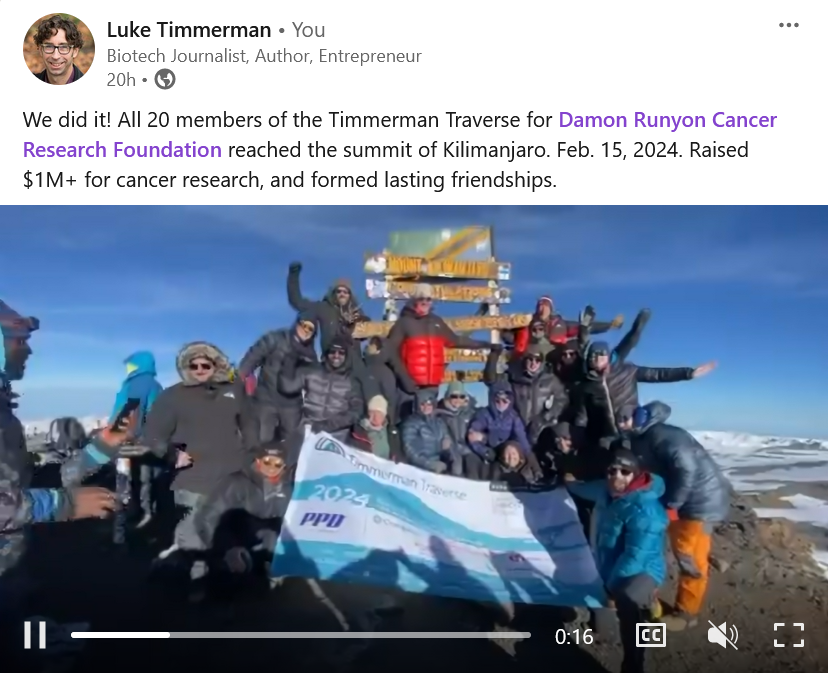

One, I’m pleased to announce two new Timmerman Traverse campaigns in 2024. One is for Life Science Cares with a focus on fighting poverty around the US. The next one is for Sickle Forward, a nonprofit devoted to improving newborn screening and treatment of sickle cell disease in Africa. Both campaigns are loaded with biotech leaders working to raise $1 million. For more information about who’s on the team and how to contribute, go to TimmermanReport.com and click on “Traverse.”

Second, I have a job opening. I’m looking for a business representative. This person will be asked to sell group subscriptions to Timmerman Report, sell sponsorship packages to The Long Run podcast, and negotiate my speaking engagements. This position will pay a base salary plus commissions. The ideal candidate is someone seeking to grow their knowledge and network in the biotech industry. Interested? luke@timmermanreport.com

Now please join me and David Liu on The Long Run.