Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

18

Feb

2025

Defend the FDA

Luke Timmerman, founder & editor, Timmerman Report

We need a competent, well-supported, tough and independent food and drug regulator in this country.

We need that independent cop on the beat so we can have confidence that the medicines, vaccines, diagnostics and devices at the core of modern healthcare have passed the scrutiny of an uncorrupted, scientifically grounded and ethical group of people working in the public interest.

If the new Trump Administration wants to focus on cutting waste and the thicket of senseless bureaucratic rules and craft attitudes that slow down innovation, OK. If it thinks regulation might work more smoothly if drugs and food were under separate management, I’m listening. If it wants to ditch industry user fees, as long as the FDA budget is fully supported by citizen-taxpayers, that’s not a bad idea.

But if this Administration cuts so deep that the FDA can’t do its job, because it thinks only a fig leaf of regulation helps business interests, then we have a problem.

We’ll have a Wild West of medicines being shilled online much like vitamin supplements based on unsubstantiated or false claims. If the budget slashers go too far, we’ll turn back the clock to the snake oil days that would make impossible medicine’s “first do no harm” credo.

That would be a terrible mistake. Biotech and pharmaceuticals are brimming with potential.

The FDA has always had a complex relationship with industry. It has had, and will always have, clashes with industry over how much evidence is necessary to approve a medicine, what the right safety–efficacy balance is for a given situation, or what a valid clinical trial design ought to look like to prove the benefits of a medicine outweigh its risks.

The FDA has always had critics. Always will. It will make mistakes because no one, and no agency, is perfect. But at a high level of budgetary policy, the problems at FDA stem more from being understaffed than from being overstaffed.

The agency has been underfunded and neglected through its history. Members of Congress and Presidents don’t win elections on abstract ideas like maintaining a safe and effective supply of medicines, vaccines, diagnostics and medical devices. The agency is mostly invisible, operating in the background.

Big budget increases haven’t come from members of Congress. In the 1990s, AIDS activists were furious over the bureaucratic bottleneck that caused new drug reviews to drag on for more than two years on average. Those patient advocates banged on the door and demanded the FDA review new treatments for AIDS as if their lives depended on them.

That activism paid dividends. It led to the Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992, which has been renewed every five years since. That law created the user-fee structure that speeds up drug reviews, and which now delivers about half of the FDA’s $7.2 billion annual budget.

Questions

In the midst of reassessing the consistently underfunded FDA budget, we should be asking some hard questions:

- How much of the agency’s budget should come from user fees? How much is too much?

- Does the FDA have enough people to regulate the current and coming tidal waves of biomedical innovation?

- Can it efficiently handle hundreds of new applications for cell and gene therapies, which are more complicated to evaluate than typical small molecule pills?

- Does it have the facilities and updated high-tech equipment it needs?

- Does it have credible leadership capable of hiring great people and inspiring them to fulfill the agency’s mission?

- Will the new commissioner be capable of communicating the nuanced value of the FDA to Congress, the President, and the public?

In the spirit of bold, ambitious thinking about re-imagining government that’s more efficient and accountable to the citizens, I’d like to propose a few ideas to reimagine and improve the FDA.

Move out of Washington, DC. The FDA doesn’t need to be in Washington. The FDA has almost 20,000 employees. Not all are in Washington, but many are. Scientific review teams can do their jobs anywhere, and it might be best to do the job in a quiet place free from excessive influence from Congressmen, the White House, or industry lobbyists.

By moving the FDA out of Washington, the federal government could find some budget savings. The FDA has valuable land that could be redeveloped by private developers of mixed-use business and residential properties. FDA could take the proceeds and build an integrated campus in the middle of the country on cheaper land.

How about Wichita, Kansas (pop. 390,000) or Tulsa, Oklahoma (pop. 411,000) or Milwaukee, Wisconsin (pop. 561,000). These cities offer relatively lower living costs and high quality of life. They have diverse demographics with White, Black, Hispanic and Native American populations that closely reflect the population of the country. The FDA, operating down the street from healthcare providers in a place like this, could test promising initiatives in a “real world” healthcare setting.

Done right, the FDA could gain valuable insights into how to operationalize things like telemedicine for clinical trials, remote patient monitoring, and more efficient ways to gather a range of data types from genotype to phenotype. These initiatives could modernize the clinical trial enterprise.

By doing what it does differently, and better, the FDA could speed up drug R&D and lower the cost of what it takes to develop a new medicine. It could do that without undermining safety, and in a transparent way that builds back public trust in biopharmaceutical R&D.

FDA workers could put down roots and be good scientific citizens in their communities. They would be parents of kids in local schools, and neighbors to ordinary people.

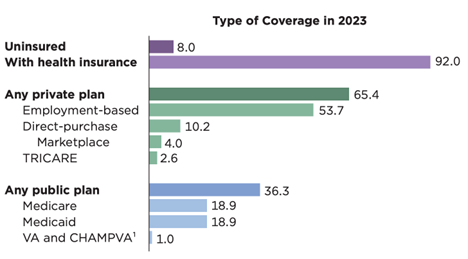

Double the budget over five years while reducing user fees. The FDA has always had to struggle for resources. When it succeeds, no one notices. When it screws up, it’s headline news. The FDA doesn’t get to bask in the glory of discovery like the NIH. Its public health mission sometimes puts it crosswise with powerful constituents, like drugmakers or tobacco companies or Big Agriculture. The FDA doesn’t have a lot of natural allies in Congress who understand or enthusiastically support its multi-faceted work. Its budget, at $7.2 billion for 2025, is small potatoes for an agency that regulates one-fifth of the US economy. How is it supposed to monitor manufacturing facilities and supply chains around the world to keep us safe from contaminated or counterfeit medicines?

For more than 30 years, the agency has long been kept on a tight leash in Congress and has been forced to rely increasingly on industry user fees. Almost half of the FDA budget—$3.5 billion a year—comes from these fees that companies pay for the agency to review applications.

That’s one way to save a few taxpayer dollars. But it also creates a financial dependence on industry, and a closeness that can sometimes get a little too close in ways that are subtle and hard to quantify. I think there’s a place for user fees in the FDA budget, much like we pay user fees to visit National Parks. But the lion’s share of the agency’s budget ought to come from us, the taxpayers. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. isn’t entirely wrong to question this arrangement, although he goes too far in making broad-brushstroke claims of corruption.

With so many groundbreaking biopharma products coming down the pike, the FDA needs double the budget just to keep with the anticipated demands on this overstretched agency.

Pay Attention to the New Commissioner. The FDA acting commissioner since Jan. 24 is Dr. Sara Brenner. She’s an agency veteran, a physician and a public health advocate. She has deep experience in the diagnostics group at FDA and worked on the COVID-19 response. That might make her a short-timer in the role, as there are still plenty of hard feelings in the public about the way the pandemic was managed.

At a moment when the agency needs to restore public trust and break out of some of limited thinking of the past, it needs a commissioner with excellent communication skills and a vision for a 21st century FDA. The next FDA commissioner needs to communicate to the public and advocate passionately with leaders on Capitol Hill and the executive branch. Scott Gottlieb was skilled at this part of the job and understood how to strike the balance of protecting public health while facilitating quality development of new products.

Marty Makary

I’m thinking of someone to lead the FDA who has public health experience, who believes in the FDA mission to the bone, who can communicate scientific risk / benefit equations to a Nobel laureate or your grandma, and who doesn’t have too many industry conflicts.

Dr. Marty Makary of Johns Hopkins University is the nominee from President Trump. He’s a physician and a health policy expert. He has written guest editorials in major news outlets and appeared on FOX. He’s written bestselling books. He was critical of government policies during COVID. I haven’t interviewed Dr. Makary, but his qualifications for the job appear solid. I would like to hear him outline his vision for the FDA in front of the Senate.

Get Ahead of the Trends with PDUFA VIII. The Prescription Drug User Fee Act, the governing compact that has set the terms of engagement between industry and FDA since 1992, is renewed and updated every five years. The current iteration of PDUFA is due to expire in September 2027. It may seem far off, but behind-the-scenes negotiations between industry and the agency often take more than a year. The industry and agency will have to discuss fundamentals like fee rates, support for new initiatives, and allocating resources to keep up with the agency’s mission. It’s not too early to think about a new bargain.

Besides the need for more staff, there’s always a need to stay current with information technology, and lab technology tools, to keep up with an industry that is well-funded and moving faster than ever. The agency also needs resources for staffing up far-flung field offices so it can adequately do facility inspections, especially with the vast array of generic drug facilities around the world and the boom in biologic manufacturing here and abroad.

If we don’t make this investment, we can expect a slowdown in new product approvals—an abundance of innovations that can’t get all the way to people. It would be an “innovation pile-up” reminiscent of a Third World country.

If we’re smart, we’ll invest now to get ahead of the curve.

A visionary and well-funded FDA could consider master protocol study designs that could cut down on some of the inefficiency that bogs down many clinical trials today, like legalese in informed consent forms or slow Institutional Review Boards that are inconsistent from site to site. There are too many small, single-site, investigator-sponsored studies—small and crappy trials that never yield clear-cut answers. The FDA is the one agency that can take the lead on demanding new standards.

It’s easy to overlook the FDA. It’s easy for companies, investors, journalists and former FDA people to criticize. Often, we’re right when we do. It needs our scrutiny, our tough, independent and fair-minded questioning.

But the FDA also needs our support. It deserves our most creative, constructive ideas on how to fulfill its mission. We shouldn’t take it for granted. The pharmaceutical industry wouldn’t be worth much if the FDA were to wither on the vine.

We can’t allow that to happen. I don’t think it will. Let’s revitalize the FDA, and put it in position to be great at what it does for the next 100 years.