Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

11

Jan

2022

Antibody Engineering & Company Building: Bassil Dahiyat on The Long Run

Today’s guest on The Long Run is Bassil Dahiyat.

Bassil is the CEO of Monrovia, Calif.-based Xencor.

He’s been on a true Long Run.

Bassil Dahiyat, co-founder and CEO, Xencor

Bassil co-founded Xencor in 1997 after getting his PhD in chemistry at Caltech. He’s been through a lot of ups and downs in the biotech markets, and taken the company through a couple big strategic shifts.

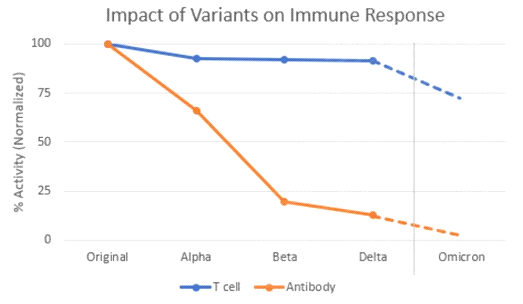

The company is known for its work on engineering monoclonal antibody drugs, and engineered cytokine therapies. Few people may realize it, but the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab, developed by VIR Biotechnology and GSK as a broadly neutralizing antibody that still works against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, was made with help from the antibody engineers at Xencor.

Antibody engineering has come a long way over the past 20 years. These treatments are crucial to the present and future of medicine. Bassil has seen the evolution at close range.

Xencor is now aspiring to make a difference for its partners, but also to develop a few drugs of its own.

This is a fun, freewheeling, insightful conversation with a scientific entrepreneur.

Now, before we get started, a word from the sponsor of The Long Run.

Today’s sponsor, Answerthink, has been consistently recognized by SAP, one of the largest enterprise software companies, as a top business partner for delivering and implementing SAP solutions for small and midsized life science companies. Their SAP certified solutions designed for the Life Science Industry are preconfigured, rapidly deployable and address fundamental business and IT challenges such as:

- Integrating your business applications

- Delivering validated reporting

- Increasing your speed to market

- Support for global rollouts

- As well as delivering a fully compliant solutions that meets FDA’s strict standards.

Explore how Answerthink can streamline your business processes to ensure growth.

Visit Answerthink.com/timmerman and get a copy of the e-book- “Top Three Barriers to Growth for Life Science Organizations.“

That’s Answerthink.com/timmerman

Now please join me and Bassil Dahiyat on The Long Run.