Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

8

Feb

2021

An IPO Bonanza, FDA Clears BMS CAR-T, and AVROBIO Gene Therapy Dazzles

Please subscribe and tell your friends why it’s worthwhile. Quality journalism costs money. When you subscribe to Timmerman Report at $169 per year, you reward quality independent biotech reporting, and encourage more.

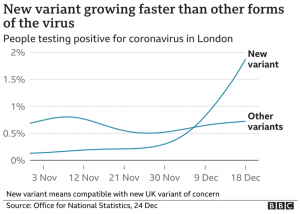

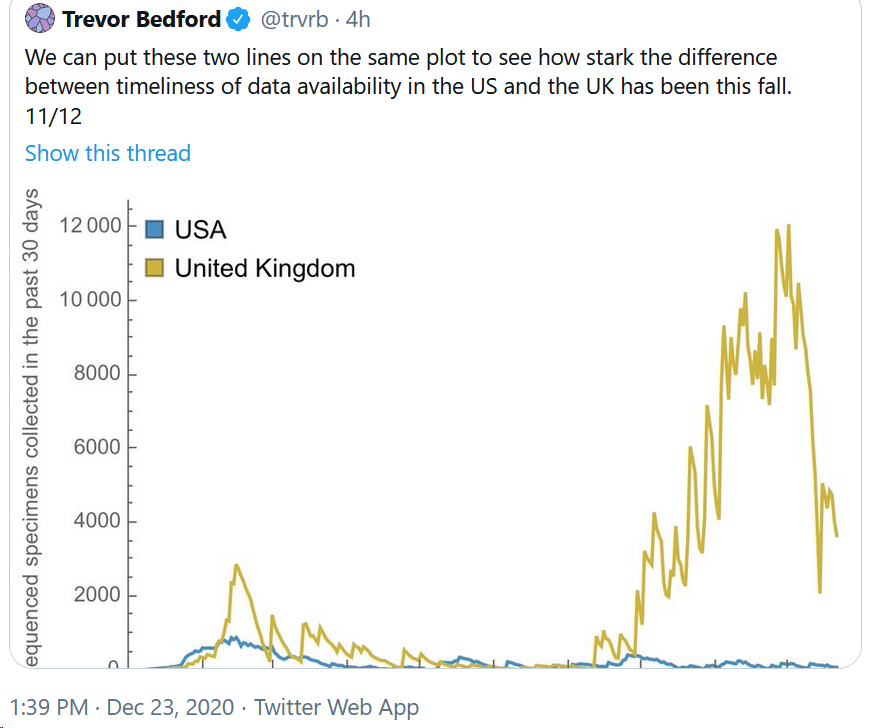

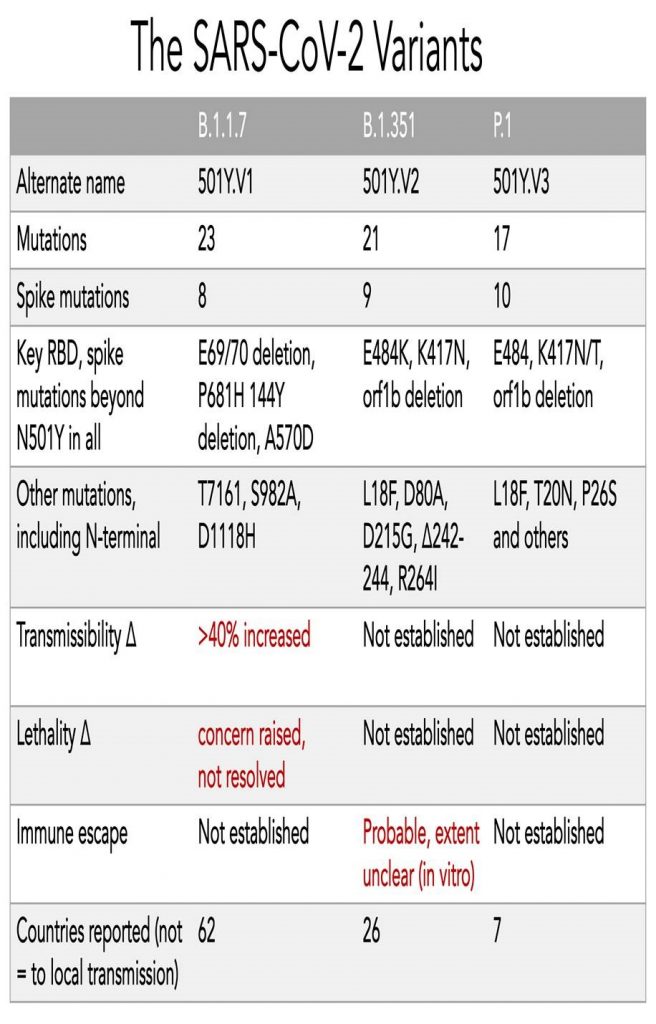

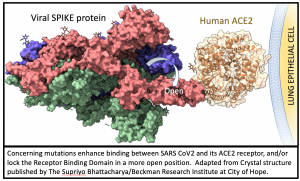

All mutations that are incorporated into virus strains that spread out geographically and grow faster than their predecessors are a “smoking gun”. This is exactly what has happened in the United Kingdom over the past three months and may be happening again in South Africa. The most recent analysis of the UK strain (B.1.1.7; aka VOC-202012/01; aka 20B/501Y.V1) combines prior laboratory findings (

All mutations that are incorporated into virus strains that spread out geographically and grow faster than their predecessors are a “smoking gun”. This is exactly what has happened in the United Kingdom over the past three months and may be happening again in South Africa. The most recent analysis of the UK strain (B.1.1.7; aka VOC-202012/01; aka 20B/501Y.V1) combines prior laboratory findings (