Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

21

Sep

2020

What We Know About COVID-19, and What We Don’t

Alex Harding, MD.

He or she will have had fever and chills for the past few days, severe fatigue, muscle aches, and cough. They have no interest in food. They will have felt short of breath when doing the mildest of tasks, such as walking upstairs in their house.

They might have had some lightheadedness and may say that they feel chest pain or tightness—they place their hand over their breastbone as they say it—when they take a deep breath.

Since my internal medicine clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) converted into a respiratory illness clinic at the beginning of March, I have seen around 100 patients who came to the hospital with these symptoms and later tested positive for COVID-19. Some might call this the classic presentation for mild to moderate COVID-19. But I’ve learned that there is no classic presentation for COVID-19.

More than anything else, what stands out to me is that this disease causes a tremendous variety of symptoms, with a vast range of severity.

Even more befuddling, close to half of infected people have no symptoms at all, while a significant share become critically ill, leading to mechanical ventilation, heart-lung bypass, and death. While severe disease disproportionately strikes the elderly, there are young, healthy people who develop critical illness, as well as elderly people in poor health who have no symptoms or only mild symptoms. So, while the symptoms I described are common for patients with COVID-19, they do not represent a norm.

There is no norm.

Another lesson I’ve learned is to respect COVID-19. The first patient I ever saw with the disease was a healthy man in his late 20s who walked into our temporary surge clinic in the emergency department’s ambulance bay at MGH in early March.

Although he said he was doing “OK,” his blood pressure was a bit low and I sent him to the emergency department for intravenous fluids. The next day, his condition rapidly deteriorated. He was one of the first patients with COVID-19 admitted to our intensive care units, where he had acute respiratory distress syndrome and severely low blood oxygen levels.

Since that day, I’ve seen many patients who appeared fine at one moment and yet developed severe, even deadly, symptoms mere hours later.

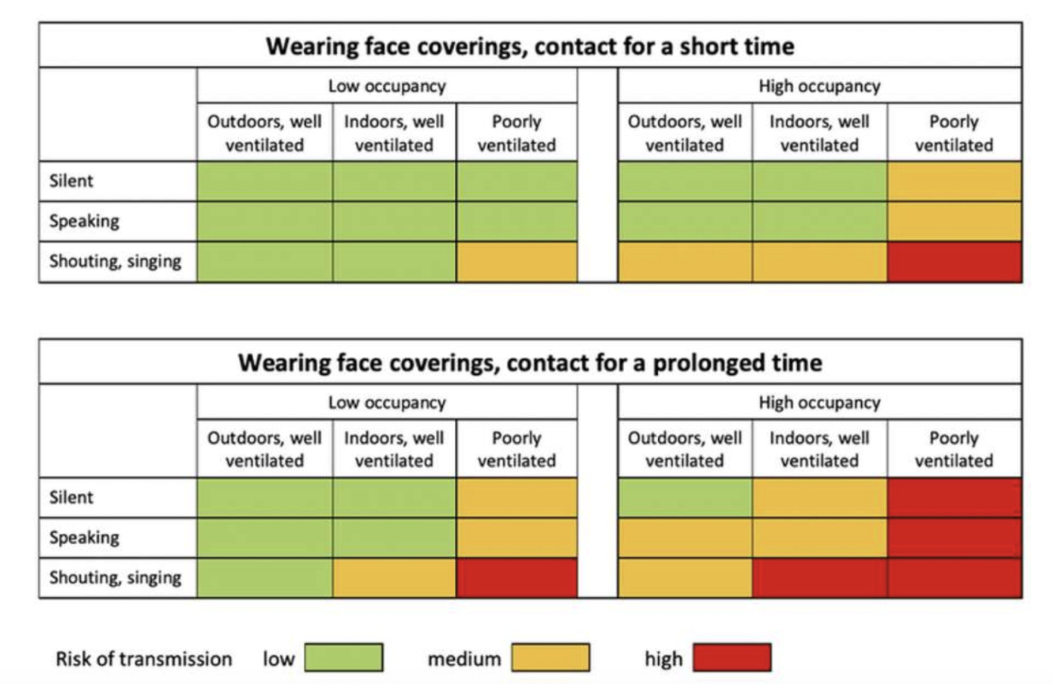

COVID-19 can do strange things. Although it’s primarily seen as a respiratory illness, and it is transmitted via respiratory droplets and aerosols, there’s no question that when people get the infection, the virus can take on protean manifestations.

Perhaps the most well-known symptom is anosmia—loss of sense of smell. While plenty of viral respiratory infections can cause loss of taste and smell, what stands out about the anosmia seen in COVID-19 is that it often precedes other symptoms like nasal congestion that normally cause lost sense of smell in other infections. I have not yet read a convincing explanation for this phenomenon, but it can be a useful diagnostic finding and does not present a life-threatening danger to patients, so it is an odd symptom I am actually grateful for, because it can be helpful as part of a clinical diagnosis.

Unfortunately, not all of COVID-19’s oddities are so benign. Another feature of COVID-19 that has gotten a lot of attention is the risk of blood clots. Any severe infection will predispose patients to blood clots, but the frequency of clots in COVID-19 is striking, with over 25% of hospitalized patients experiencing a venous clot.

The cause of clots in COVID-19 is not fully understood, although it probably involves excessive inflammatory signaling that stimulates blood to clot. Treatment is controversial, with some doctors advocating for high doses of blood thinners in hospitalized patients to prevent clots from forming, although such an aggressive approach has not been studied scientifically to assess for safety and efficacy.

It is also clear that COVID-19 can affect the heart in multiple ways. Although many patients do mention chest pain or tightness early in the disease course, I do not think that most of those patients have a problem with their heart. Nevertheless, there is a minority of patients with COVID-19 that do develop true heart problems, including heart attacks and inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis). Unfortunately (recurring theme here), the mechanism of heart injury is still uncertain but probably is related to severe systemic inflammation and perhaps direct infection of heart tissue.

There is a long list of other organs that can be affected in COVID-19. The kidney, liver, and central nervous system have gotten a lot of attention. A colleague of mine saw a patient with thyroid inflammation leading to severely low thyroid function, which was probably caused by a COVID-19 infection. It’s still unclear whether these diverse effects are caused by direct infection by COVID-19, but my suspicion is that generalized inflammation in response to the virus, rather than local infection, is the primary driver of these effects.

Other effects of COVID-19 have been overhyped or exaggerated.

Remember COVID toes? Back in April and May, it was all the rage for people to call their doctors because they had noticed spots or bumps on their toes. And it is possible that COVID-19 does rarely cause lesions on the toes, perhaps from the deposition of antibodies and other immune products in small blood vessels. But among patients who actually have COVID-19 who have come to my clinic, very, very few have had any toe lesions that could be attributed to the infection.

Instead, it’s likely that with the chilly weather here in the Northeast in April and early May, while people were staying home and more likely to be barefoot, they developed sores on their toes related to a condition called chilblains or pernio that causes sores on cold toes—completely unrelated to COVID-19 except in the sense that during the lockdown people were less likely to be wearing shoes and socks. As the weather warmed up, questions about COVID toes have gone down.

Another topic that has been exaggerated is the risk of long-term lung fibrosis after COVID-19 infection. In my role as a venture capitalist, I have seen several companies pitching new treatments to block fibrosis in patients who had recovered from COVID-19 infections. While it is too early to say anything about the long-term effects of COVID-19 with certainty, lung fibrosis does not yet appear to be a major issue. In general, it is quite unusual for acute lung infections to result in long-term lung fibrosis of any consequence for patients. Some COVID-19 patients do have some scarring in their lungs that can be seen on CT scans, but it is unlikely that this amount of scarring will significantly impair lung function.

There has also been a lot of commentary about “silent hypoxia,” where people with COVID-19 are awake and alert and yet have very low oxygen levels in their blood. This is a very real phenomenon, one that I have seen with my own eyes several times. But it is not a mysterious or magical effect specific to COVID-19. It’s basic physiology.

The sensation of shortness of breath is mainly driven by having too much carbon dioxide in the blood, not by too little oxygen. When our ancestors chased after wooly mammoths looking for a bite to eat, a fall in blood oxygen was always accompanied by a rise in carbon dioxide, so this signaling system worked out. But when there is an infection in the lungs, the oxygen level drops without a proportional rise in carbon dioxide. So, it is no surprise that some people with COVID-19 can “look OK” even when their oxygen level is dangerously low. Doctors need to be aware of this phenomenon and warn our patients to watch their symptoms very closely.

Lastly, I want to comment on patients who have symptoms for months after their initial infection with COVID-19. Some of these patients have labeled themselves ‘long-haulers.’ Very little is known about these long-term effects, but I have seen several patients with months of symptoms. The most common symptoms include severe, fluctuating fatigue, muscle aches, persistent fevers, and effects on the autonomic nervous system, which controls basic bodily functions like heart rate and blood pressure. I have seen patients with a heart rate over 110 beats per minute for weeks straight.

These symptoms may be similar to another poorly-understood condition called chronic fatigue syndrome, which can occur after other viral illnesses. There is a long-standing medical debate about whether chronic fatigue syndrome is “real.” Having seen COVID long-haulers myself, I can tell you the symptoms are very real. We need to understand what’s causing them so that we can make people better.

Over the past six months, we have all gotten way too familiar with COVID-19. Armchair experts have sprouted up all over. Hopefully, my first-hand perspective is useful, albeit anecdotal. If there is one message I would like you to take away, it’s how much we still do not know about COVID-19, especially its long-term effects.

As with so much else, more high-quality research is needed.

Alex Harding is an internal medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital who sees patients in an urgent care clinic. He is also senior director of business development at two Atlas Venture-backed startup companies. Alex was previously a senior associate at Atlas Venture.