Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

6

Dec

2021

Targeted Small Molecule Protein Degraders: Nello Mainolfi on The Long Run

Today’s guest on The Long Run is Nello Mainolfi.

Nello is the president and CEO of Cambridge, Mass.-based Kymera Therapeutics. Kymera is working on targeted protein degraders. These are orally available small molecule compounds. Many in biopharma are excited about them because they have a clever design that allows them to go after targets that have previously been out of reach for small molecules.

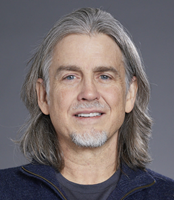

Nello Mainolfi, co-founder and CEO, Kymera Therapeutics

These compounds are sometimes called “heterobifunctional molecules.” They are “chimeras” or hybrid molecules of a sort, that engage a protein target of choice, while also recruiting E3 ubiquitin ligases. These ligases act as catalysts for the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which acts to drag proteins of your choice into the cellular garbage disposal system, where they get irreversibly degraded.

Instead of directly inhibiting a disease protein, you can latch onto it and drag it into the trash compactor. Pretty cool.

Nello is a chemist by training, and dove all-in as co-founder and VP, head of drug discovery at Kymera in 2016. It’s a pleasure speaking with him at length about this exciting area of drug discovery that doesn’t get as much media coverage as I think it should.

Today’s sponsor, Answerthink, has been consistently recognized by SAP, one of the largest enterprise software companies, as a top business partner for delivering and implementing SAP solutions for small and midsized life science companies. Their SAP certified solutions designed for the Life Science Industry are preconfigured, rapidly deployable and address fundamental business and IT challenges such as:

- Integrating your business applications

- Delivering validated reporting

- Increasing your speed to market

- Support for global rollouts

- As well as delivering a fully compliant solutions that meets FDA’s strict standards.

Explore how Answerthink can streamline your business processes to ensure growth.

Visit Answerthink.com/timmerman and get a copy of the e-book- “Top Three Barriers to Growth for Life Science Organizations.”

That’s Answerthink.com/timmerman

Absci is all about creating new possibilities in the realm of protein-based therapeutics. What does this mean?

Absci has a fundamentally different approach to drug discovery. It designs and develops next-gen biologics of any modality, from antibodies to T-cell engagers to completely novel protein scaffolds, including a futuristic format it calls “Bionic Proteins.”

Because Absci conducts its screens in its scalable production cell line, it collapses several steps of biologics discovery into one integrated, efficient process. Absci also has a unique computational antibody and antigen discovery approach for isolating fully-human antibodies from disease tissues and using these antibodies to identify novel drug targets.

Absci does all this with a powerful combination of deep learning AI and synthetic biology technologies. Absci is already helping some of the best partners in biopharma translate their ideas into drugs. Check them out at absci.com and absci.ai.

Now please join me and Nello Mainolfi on The Long Run.