Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

20

Jul

2020

Clinical Trials: High-Value Attack Surface For Pharmatech Entrepreneurs

David Shaywitz

There’s an emerging sense among early stage investors that there are profound opportunities at the intersection of healthcare and technology, and no shortage of white papers from consultants and venture groups addressing this topic.

Consultant white papers tend to be focused on the inevitability of “digital transformation,” emphasize the $X billion dollar opportunity, and argue that if large organizations don’t want to get further behind their peers, these are the steps they need to take, right now.

Basically: carrot, stick, call-to-action.

VC white papers in this space are often written by tech investors seeking to take their talents to the giant pool of money they assume awaits them in healthcare. Having seen the impact of emerging technologies on other industries, they are keen to coax benighted healthcare services and biopharmaceutical companies into a brilliant, tech-enabled future.

These vision documents typically reveal a sophisticated understanding of digital technologies, but a generalized, somewhat broad-brush, somewhat naïve, somewhat condescending view of the industry they’re proposing to either serve or disrupt (ideally one, then the other).

Enticed by what many see as a huge greenfield opportunity, more and more tech VCs seem to be taking a serious run at healthtech, as manifest in a series of dedicated investments.

Most life-science VC firms, on the other hand, seem content, as one leading Boston-based life-science VC partner told me, “to stick close to our knitting.”

In part, this may reflect the remarkable contemporary explosion of life-science innovation, largely independent of digital/data technologies. Given the range of approaches now viewed as viable involving cell therapies, gene therapies, and “multi-specific” drugs, I can appreciate (and have also seen, first-hand) how many life-science investors feel they have their hands full just sorting through this embarrassment of intellectual riches.

Even so, some venture investors with established health credibility clearly are embracing the pharma/tech interface.

By far, the most compelling expression of this I’ve encountered so far was a recent white paper from Bessemer Venture Partners, based in Boston and California. (Disclosure: I have no relationship with the group.)

One of the oldest venture firms around, and known for their arrestingly candid anti-portfolio (missed opportunities), Bessemer has historically pursued investments in both technology and health, including both healthcare services and life sciences. Recently, at least, their focus seems to be on the former — but I may be biased by the entrepreneurs featured on “A Healthy Dose,” a fantastic podcast co-hosted by Bessemer partner Stephen Kraus and focused on companies at the interface of healthcare services and technology.

The recent white paper reveals an insightful view (which is to say, one with which I largely agree) of the promising, emerging interface between tech and pharma.

The whole piece is worth a read, but there are a few highlights that seem particularly noteworthy.

Their central thesis is that the “greatest entrepreneurial opportunities live across the clinical trials value chain.” They acknowledge the activity in other areas (such as “drug discovery engines” — where so much of the AI-in-pharma buzz seems to reside — and digital therapeutics – think of Akili’s EndeavorRX, described by the FDA (the FDA!) as “the first game-based digital therapeutic to improve attention function in children with ADHD.”

In identifying clinical trials as an especially promising area, Bessemer echoes the thinking of pharma leaders like J&J head of data science Najat Khan and others, who consistently emphasize the outsized importance of finding ways to make clinical trials faster, better, and ultimately cheaper using technology.

The Bessemer team also clearly recognizes some of the key adoption hurdles emerging technologies face in pharma. These include both the general challenges of introducing change (overcoming institutional inertia, or perhaps, more accurately, lack of inertia) as well as the more specific challenges of bringing novel digital clinical trial tools and approaches into a highly regulated environment. Uncertainty around FDA acceptance of these approaches, the authors suggest, remains among the most significant hurdles.

Within clinical trials, the Bessemer team sees five somewhat distinct areas of opportunity:

- Decentralized clinical trials

- Patient recruitment

- Remote patient monitoring

- Virtual control arms and real-world evidence platforms

- Supply chain optimization

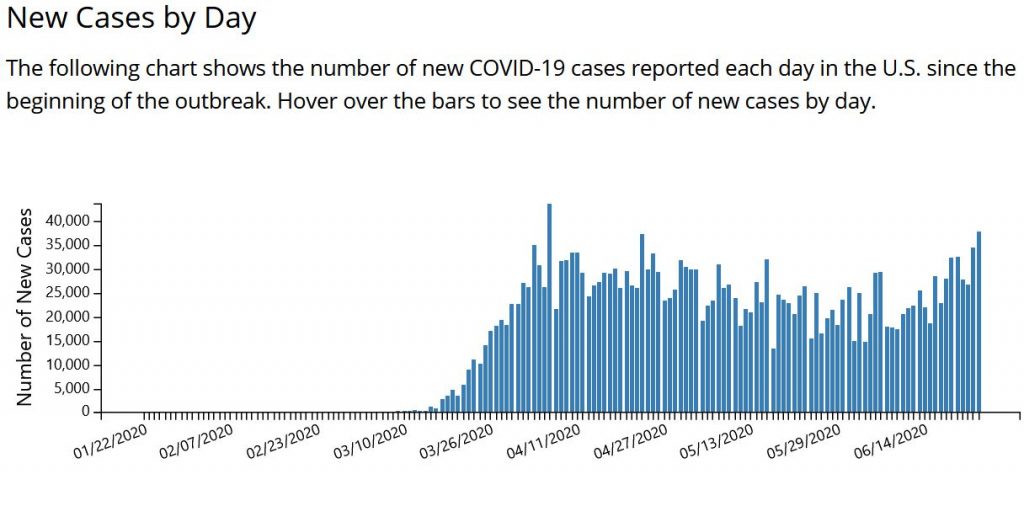

While these represented areas of interest pre-COVID-19, the pandemic has clearly thrown into sharp relief both the value and need for the intensification of investment in these areas.

In their analysis, Bessemer astutely identifies key distinctions and value drivers. For example, within decentralized trials, they wisely distinguish between approaches that basically enable trials at home (like Science37), approaches that emphasize the increased inclusion of community doctors to “diversify the pool of principal investigators” (i.e. expand beyond typical academic honchos from leading centers), and platforms that seek to integrate existing silos.

I also applaud their recognition of the central importance of patient recruitment – a central preoccupation of nearly every single person involved in clinical drug development in biopharma. This is likely to be a point of increasing emphasis as companies explicitly recognize the need to diversify clinical trials to enroll people who historically been underrepresented in the research enterprise.

Bessemer also appreciates that the ubiquity of consumer digital devices doesn’t mean the data generated by these wearables are suitable for use in clinical trials – often, they are not of high enough consistency or quality to be considered “regulatory grade.” One interesting opportunity suggested by Bessemer involves developing regulatory-grade tools on top of these devices.

Not surprisingly, I was especially interested in the discussion of real world evidence, and again, the Bessemer team seemed to capture so much of the nuance.

For example, they distinguish between “traditional” (as much as anything in this fairly new market segment can be considered “traditional”) uses of real-world data to support so-called HEOR (health economics and outcomes research) activities, generally related to reimbursement, and emerging uses.

Of particular interest: the use of virtual/synthetic control arms, which under some circumstances can help support regulatory approval; reportedly, it was this capability that prompted Roche’s $2 billion acquisition of Flatiron Health.

Bessemer also notes that many startups are concentrating (at least initially) on oncology data, while some are emphasizing other areas, like ophthalmology (Verana), rare disease (RDMD), neurological illness (Blackfynn), and mental health (Holomusk). Even here, some focus on extracting value from existing data sources, while others are trying to create “novel and differentiated data sets.”

Finally, Bessemer highlights the opportunities in “supply chain optimization,” and in particular, the need to “connect various stakeholders to improve upon manufacturing execution systems.”

Here, my improvised reaction was “yes, and….” As we’ve repeatedly heard from Novartis and others, there are huge opportunities to drive unsexy but critically important operational efficiencies throughout pharma, and tools that can catalyze this will be critically important.

Bessemer also highlighted several subtle strategic points that were especially insightful. One example: emphasizing the value of close collaboration with the FDA, not only in seeking specific approval, but, at a deeper level, in helping the agency evolve its policy, as it seeks to define where it needs to go in the future.

This seems exactly right; agency leaders including former Commissioner Scott Gottlieb and current Deputy Director Amy Abernethy have explicitly recognized the rapid evolution of this area, and have acknowledged the need to find a way to incorporate the opportunities afforded by new technology while remaining laser-focused on the FDA’s underlying commitment to ensuring public safety. By engaging in this policy discovery process, entrepreneurs can support their own companies while also helping the agency achieve this shared long-term goal.

One area that I might have explicitly emphasized as well is the need to similarly engage with biopharma partners; successful pharmatech (as Bessemer calls this space – I like the term) entrepreneurs will appreciate the need, especially initially, to deeply engage with and learn from pharma partners, so the technology the startup is developing is aimed squarely at a critical problem the pharma company faces.

Companies skilled at enterprise sales (Palantir comes to mind) are especially good at burrowing in really intensively, to surface the most suitable problems to effectively address.

My advice to pharmatech entrepreneurs:

Startups afforded the opportunity to work with pharma partners would do well to use their time searching for and constantly refining what they could be doing, not just pitching and pushing what they’re already doing.

At the same time – and this is something Bessemer explicitly emphasizes, in the context of platform-as-a-service offerings, and may be true more generally – entrepreneurs must balance the ability to deliver highly bespoke solutions with the goal of developing “scalable platforms that can be deployed quickly and generate predictable recurring revenue.”

Successful examples of this, I’d argue, include Veeva in biopharma, and Epic in healthcare. The traction of Epic, in particular, highlights the value of even highly-customized solutions, provided they are viewed (at least by those paying for them, and hopefully — though perhaps not in Epic’s case — by those using them) as delivering exceptional value to the client as well.

Bottom Line

There are tremendous opportunities in pharmatech for entrepreneurs who understand not only the potential of emerging technologies but also the business needs – and organizational dynamics – of contemporary biopharma organizations. The almost unimaginably high costs and exceptional complexity of clinical drug development represents an attractive, high-value attack surface, where the utility of effective solutions can be rapidly, palpably appreciated.