Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

11

Feb

2021

Long COVID’s Insidious Toll, Novo’s Victory Against Obesity, & Gilead’s Stumble in IPF

Luke Timmerman, founder & editor, Timmerman Report

Our culture tells us to fear death.

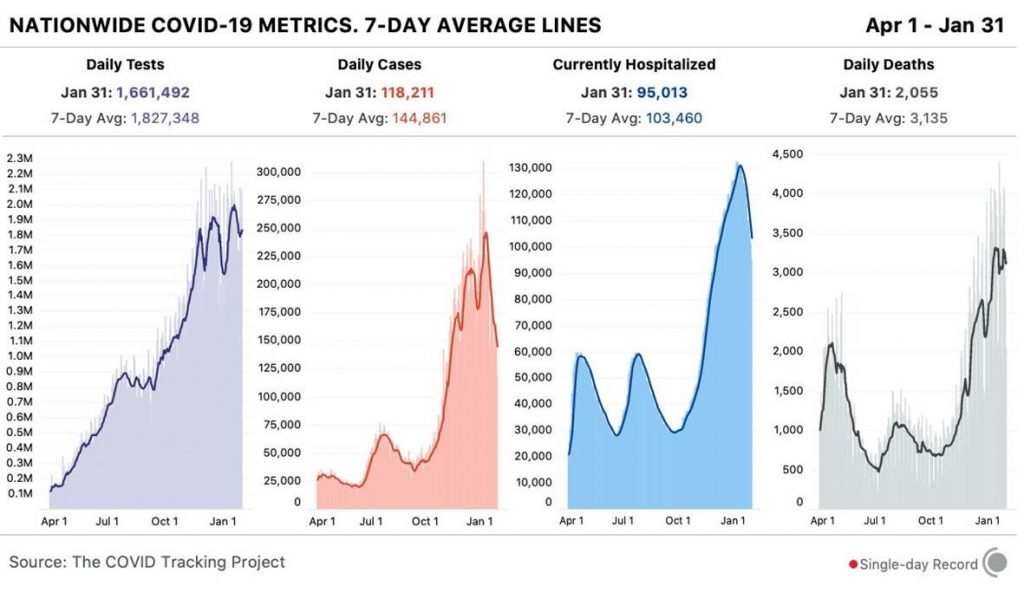

Every day, we hear updates on the COVID-19 death toll. Deaths are broken down by age, race, ethnicity. By state and nationality.

The US numbers – 473,000 and increasing by more than 3,000 a day – are tragic and numbing.

But while we fixate on death, we are devoting scant attention to the insidious, cumulative toll of morbidity from COVID-19. The ‘Long COVID’ story is one of those gradual ones that sneaks up on us over time.

The types of symptoms, the number of people struggling, the severity of chronic disease, how long the symptoms might last – these are all important questions are only beginning to come into focus.

The Mt. Sinai Center for Post-COVID Care in New York estimates that 10 to 30 percent of all COVID patients will suffer from long-term symptoms. As of this writing, we have had 27.3 million confirmed cases of COVID-19. That’s an undercount, but if you use that number for the sake of argument, we could be looking at 2.7 million-8.2 million people in the US alone who are struggling with some sort of chronic disease stemming from COVID-19.

Doctors who see COVID patients are telling me that Long COVID is the real thing, not just a few anecdotes here or there, and not some minor bellyaching from hypochondriacs as was sometimes implied by some stressed-out clinicians early in the pandemic.

“The Long Haul story is not one that has been fully told,” said Peter Hotez, a virologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and director of vaccine development at Texas Children’s Hospital Center, in a recent appearance on CNBC. “Literally millions of people could have some lingering symptoms.”

Deaths are “the tip of the iceberg,” Hotez said.

What are common Long COVID symptoms?

- Lung fibrosis / shortness of breath

- An inability to concentrate, or “brain fog”

- Blood clotting

- Heart arrythmias

- Kidney damage

- Metabolic dysregulation that looks like Type 1 diabetes

- Long-term fatigue

- Depression and anxiety that stems from any of the above chronic conditions

Data are just beginning to surface to tell the story. A 6-month follow-up study from Wuhan, China, published last month in The Lancet, found that 63 percent of COVID-19 survivors complained of fatigue and muscle weakness, and 26 percent reported sleep difficulties. About one out of every four people discharged from the hospital reported depression or anxiety. One-fourth of patients were unable to reach the lower limit of normal distance on the 6-minute walk test.

Tony Fauci has described some of the symptoms as similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis (aka chronic fatigue syndrome). While lingering inflammation may be a common thread in the two conditions, the set of symptoms don’t exactly overlap. To collect more data from Long COVID patients, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is conducting an online survey. It hopes to recruit 25,000 participants. (Survey Here).

My hope is that in the coming weeks, as our country continues to ramp up the biggest vaccination campaign in history, that we keep these devastating long-term consequences in mind.

I’ve heard stories in my extended family. There’s a distant cousin, a 20-something college undergraduate. She dropped out of college because of brain fog from Long COVID. She can’t concentrate. She’s unsure if or when she’ll be able to go back.

What must that be like, to be 21 and get a bug that doesn’t seem too terrible at first, but that ends up altering the trajectory of your life?

Often, the Long COVID effects show up in middle-aged, healthy people. Recall the Dec. 7 TR article by Blair Clark-Schoeb. She’s in her mid-40s, a parent, an athlete, and a successful biotech professional.

E. Blair Clark-Schoeb, SVP of communications, Aruvant Sciences

Her struggle with Long COVID began in March. It continues. She described it on a recent podcast.

Entire biotech funds will probably be raised in the months ahead to deal with the whole new set of chronic diseases that our healthcare system will have to confront. There will be ideas for treating chronic inflammation, for the clotting disorders, the depression, the anxiety, the diabetes-like symptoms.

The demand for biopharma to step up and deliver will be clear.

That’s a good thing. It will give purpose and drive to many in this industry. If biotech can rise to the occasion with vaccines, therapies and diagnostics, it can find a way forward here.

The main thing to remember in the urgent here and now is the importance of hunkering down for another couple of months, with masking and distancing, until the vaccines have a chance to crush the curve.

I’m much more optimistic than I was at the start of the year, because we have not just two outstanding vaccines, but two more excellent and practical options on the way from J&J and Novavax.

Let’s do everything we can to help everyone see why getting vaccinated is so vital, and so urgent. It’s not only about saving lives. It’s about helping us all live long and healthy lives.

Public Health

The CDC – still the world’s premier epidemiology and public health agency – screwed up big-time with testing at the start of the biggest pandemic in a century. Things got worse when it was muzzled and marginalized. But now that CDC has a capable leader in Rochelle Walensky with support from the White House, the CDC is in a stronger position to bring down community transmission. To that end, the CDC urged the public to consider “double-masking” as a more rugged defense against the more troubling B117 and B.1.351 variants now in circulation. For more, see this Feb. 10 JAMA article on “Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread” by a couple of CDC scientists.

Vaccine Hesitancy

The CDC reported on vaccine hesitancy in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), and the numbers are moving in the right direction. If you group together respondents who said they were “absolutely certain,” or “very likely,” or “somewhat likely” to be vaccinated, the intent to get vaccinated increased overall from September (61.9%) to December (68.0%). Those household surveys, it should be noted were taken during the intense emotions of election season, news reports of astounding efficacy for Pfizer and Moderna, and FDA Emergency Use Authorizations in December.

People age 65 and older, the ones at highest risk of COVID-19, showed increasing willingness to get the shot.

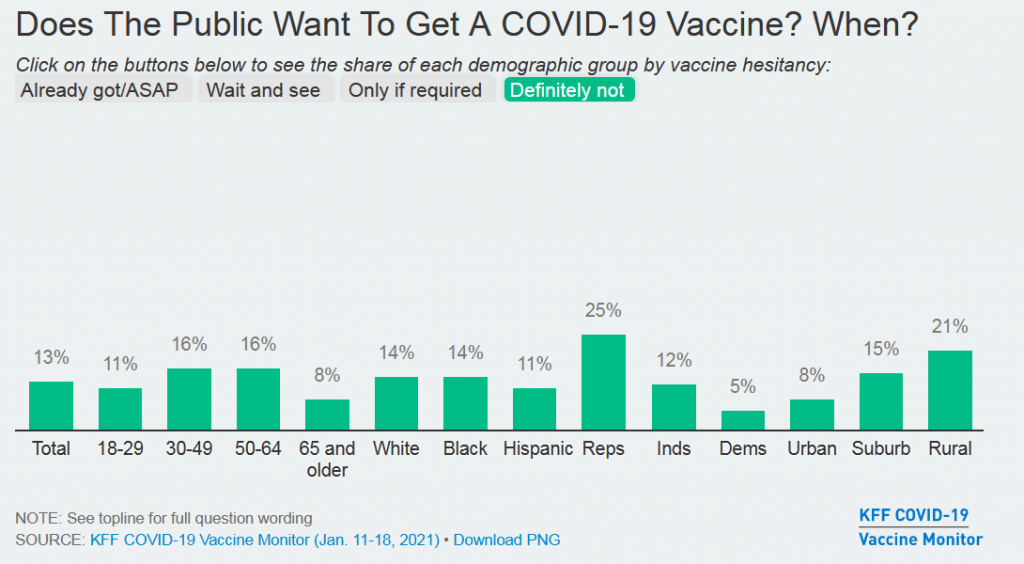

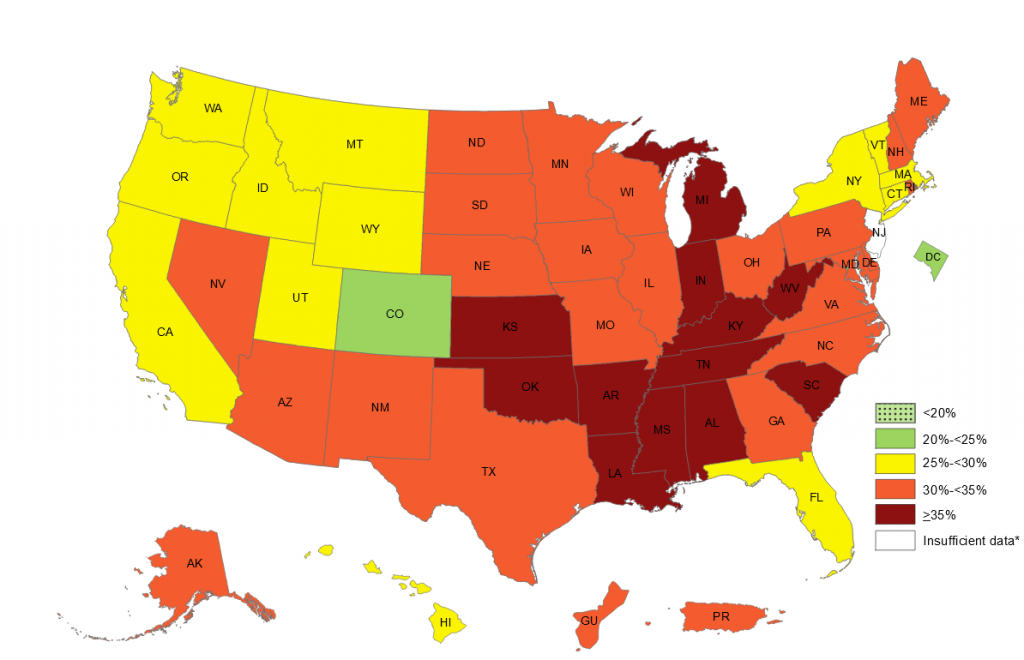

And yet, the pockets of resistance are high, and stubborn. See this recent snapshot from the Kaiser Family Foundation Vaccine Tracker. The percentages below are people who say they will “Definitely Not” get a COVID-19 vaccine. That’s 13 percent of the country, including 25 percent of Republicans and 21 percent of Rural people. (Survey data: Jan. 11-18, 2021)

Some people, on the extreme left and right, are going to be unreachable in their anti-vaccine attitudes. Maybe the biggest area of concern are the people who are in the middle, suffering from the breakdown of trust, the epistemic crisis at the bottom of the barrel of cynicism. Millions of people don’t know who or what to believe. As David Shaywitz wrote here last week, this is the result of “manufactured nihilism.”

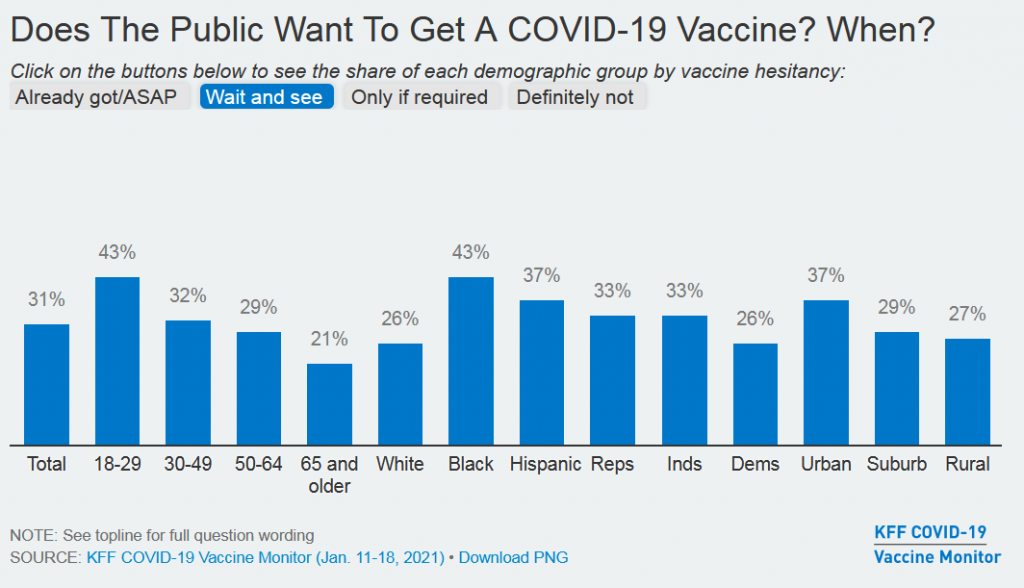

The results are plain to see. Weeks after news about 95 percent effective vaccines becoming authorized by the FDA – one of the greatest achievements in the history of science – we still see huge swaths of the US public struggling along, saying they’ll “Wait and See.” (See the demographic breakdown from the Kaiser Family Foundation survey, Jan. 11-18.)

Will these numbers trend in ever-more positive directions in coming weeks and months? I hope so. The NYT ran an editorial co-signed by 60 Black members of the National Academy of Medicine urging African Americans to get vaccinated. The Kaiser Family Foundation notes that openness to vaccination tends to increase when people know someone else who has been vaccinated.

Treatments for COVID-19

Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for Covid-19. NEJM. Feb. 11. (WHO Solidarity Trial Group)

Tocilizumab IL-6 inhibiting therapy in COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital. Overall, 596 (29%) of the 2022 patients on tocilizumab and 694 (33%) of the 2094 44 patients on usual care died within 28 days. MedRxiv. Feb. 11. (RECOVERY trial group)

Good News for Obesity

Researchers reported that once-weekly subcutaneous injections of semaglutide (Ozempic), a GLP-1 peptide analog drug for diabetes from Novo Nordisk, significantly increased weight loss when boosted up to a 2.4 milligram dose (the drug is usually given in a 0.5 to 1 mg subcutaneous once weekly shot for diabetes).

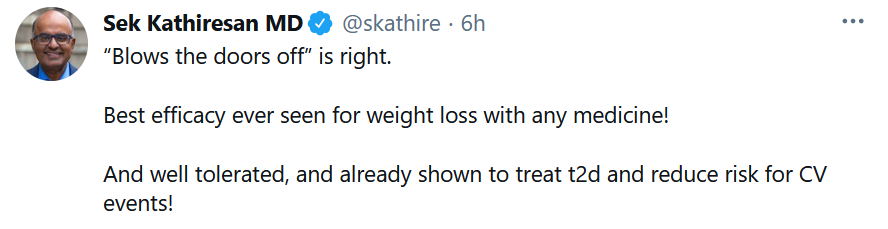

The mean change in body weight from baseline to week 68 was −14.9% in the semaglutide group compared with −2.4% with placebo, according to investigators from the STEP1 trial, writing in the New England Journal of Medicine. Nausea and diarrhea were the most common side effects; but were typically mild to moderate and went away over time. See comment from Sek Kathiresan, a cardiovascular genetics expert, and CEO of Verve Therapeutics.

Given the huge and rising prevalence of obesity in the US, this is maybe the most clinically relevant result I’ve seen on a population level in a long time. See the CDC state-by-state graphic below that shows rates of obesity, defined as people with Body Mass Index of 30 or higher. Obesity, by the way, is an added risk factor for COVID-19 complications.

Variants vs. Vaccines

- mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Feb. 10. (Michel Nussenzweig et al Rockefeller University)

- Coronavirus Variants and Mutations. An Excellent Graphic. Feb. 11. (Jonathan Corum and Carl Zimmer)

- Variants mean the coronavirus is here to stay — but perhaps as a lesser threat. Washington Post. Feb. 9. (Carolyn Johnson)

- Could a Single Vaccine Work Against All Coronaviruses? NYT. Feb. 9. (Carl Zimmer)

- Herd Immunity Might be Unattainable. But Vaccines Can Still Help End the Pandemic. The Atlantic. Feb. 9. (Sarah Zhang)

- Mapping Which Coronavirus Variants Will Resist Antibody Treatments. NIH Director’s Blog. Feb. 9. (Francis Collins)

- S. rushes to fill void in viral sequencing as worrisome coronavirus variants spread. Science. Feb. 9. (Meredith Wadman)

Epidemiology

- Quantifying asymptomatic infection and transmission of COVID-19 in New York City using observed cases, serology, and testing capacity. PNAS. (Rahul Subramanian et al)

- The effects of school closures on SARS-CoV-2 among parents and teachers. PNAS. (Jonas Vlachos et al Stockholm University)

- The role of children in the spread of COVID-19: Using household data from Bnei Brak, Israel, to estimate the relative susceptibility and infectivity of children. PLoS Computational Biology. Feb. 11. (Itai Dattner et al)

Science of SARS-CoV-2

- Exhaled aerosol increases with COVID-19 infection, age, and obesity. PNAS. (David Edwards et al Harvard University)

- Rapid Coronavirus Tests: A Guide for the Perplexed. Nature. Feb. 9. (Georgia Guglielmi)

- COVID-19 immune signatures reveal stable antiviral T cell function despite declining humoral responses. Cell Immunity. Feb. 9. (Agnes Bonifacius et al Hannover Medical School, Germany)

- Seasonal human coronavirus antibodies are boosted upon SARS-CoV-2 infection but not associated with protection. Cell. Feb. 9. (Scott Hensley et al Penn Medicine)

Access and Distribution

The US government agreed to order 100 million more doses of the mRNA vaccine from Moderna. That means that US government has agreements to get 300 million doses out of the 631 million doses Moderna has lined up in supply agreements with governments around the world.

Merck is reportedly in negotiations with governments, public health agencies, and other companies to fire up its considerable capabilities for manufacturing COVID-19 vaccines. The Kenilworth, NJ-based company, one of the world’s major vaccine producers, scrapped its novel vaccine programs after they failed to generate an adequate immune response.

Pharmacies around the country were due to get 1 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines from the federal government as of yesterday, Feb. 11. The companies, including national chains like CVS and Walmart, have confirmed they don’t want to let any doses go to waste. That raises the question of who will get leftover doses. Their employees, or the public?

A Houston doctor had 10 doses of vaccines that were due to expire, and had to be used. He gave them to people with medical conditions. He got fired and publicly humiliated for trying to do the right thing, trying to avoid a travesty. This is one of those zeitgeist stories about a society suffering from a breakdown of trust. (NYT, Feb. 10, 2021)

Our Shared Humanity

Vaccinated People Are Going to Hug Each Other. Julia Marcus writes: “The vaccines are phenomenal. Belaboring their imperfections—and telling people who receive them never to let down their guard—carries its own risks.” The Atlantic. Jan. 27. (Julia Marcus of Harvard Medical School)

Pandemic Effect on Cancer R&D

- Dramatic drop in new cancer drug trials during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. Feb. 4. (Emma Wilkinson)

- Cancer groups aim to broaden clinical trial participant pool. Bloomberg Law. Feb. 9. (Jeannie Baumann)

Financings

South San Francisco-based Day One Biopharmaceuticals, the developer of pediatric cancer drugs, raised $130 million in a Series B deal led by RA Capital Management. (Timmerman Report coverage).

Boston-based Ensoma raised $70 million in a Series A financing to develop adenoviral vectors for cell therapies that can be made more accessible around the world. 5AM Ventures led. Ensoma also announced a partnership with Takeda Pharmaceuticals to work on in vivo gene therapies for up to five rare disease programs. (Timmerman Report coverage).

Menlo Park, Calif.-based PacBio, the developer of long-read DNA sequencing instruments and technology, raised $900 million in convertible debt from an affiliate of Softbank Group.

London-based Quell Therapeutics, a developer of T-regulatory cell therapies, expanded its Series A to $84 million.

New York and Stamford, Conn.-based Sema4 went public by combining with a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) sponsored by Casdin Capital and Corvex Management. Sema4 describes itself as an “AI- and machine learning-driven patient-centered genomic and clinical data intelligence company.” The deal is expected to bring $793 million in total cash.

Seattle-based Nautilus Biotechnology, a proteomics company, merged into a SPAC sponsored by Perceptive Advisors, going public in a deal that’s fetching about $350 million. (TR coverage of Nautilus, June 2020).

New York-based Nuvation Bio went public via a merger with a SPAC sponsored by EcoR1 Capital. Nuvation, led by former Medivation CEO David Hung, is working on novel cancer drugs. It secured $646 million through the SPAC and related transactions, bringing its cash balance to $830 million.

Vancouver, BC-based Notch Therapeutics raised $85 million in a Series A financing to develop induced pluripotent stem cell-derived therapies for cancer. Allogene Therapeutics, Lumira Ventures, and CCRM Enterprises Holdings, EcoR1 Capital, Casdin Capital, Samsara BioCapital, and Amplitude Ventures participated.

Cambridge, Mass.-based KalVista Pharmaceuticals raised $193 million in a stock offering at $36 a share. It’s developing small molecules against hereditary angioedema and diabetic macular edema.

San Mateo, Calif.-based Sagimet Biosciences raised $80 million in a crossover financing. Its lead program is for NASH.

San Diego-based Pipeline Therapeutics said it raised $80 million in a Series C financing to advance its work on small molecules for neurodegeneration. New investors include Perceptive Advisors, Franklin Templeton, Casdin Capital, Samsara BioCapital, and Suvretta Capital.

Menlo Park, Calif. and Boston-based Adicet Bio raised $120 million in a stock offering. It’s working on allogeneic T cell therapies.

Lexington, Mass.-based Cyteir Therapeutics, the developer of synthetic lethal cancer drugs, raised an $80 million Series C financing. RA Capital Management led.

Baltimore, Maryland-based Personal Genome Diagnostics, a cancer genomic profiling company, raised $103 million in a Series C deal led by Cowen Healthcare Investments.

San Francisco-based Adagene, the developer of antibody drugs for cancer, raised $140 million in an IPO at $19 a share for American Depositary Shares.

San Carlos, Calif.-based BigHat Biosciences raised $19 million in a Series A financing to advance its AI-guided antibody design platform. A16Z led.

London-based Autolus, a T-cell therapy developer, raised $100 million in a stock offering.

Charlottesville, Virginia-based Hemoshear Therapeutics, the developer of treatments for rare metabolic disorders, raised $40 million in a Series A financing led by Suvretta Capital.

Indianapolis-based Apria Health, a home healthcare equipment and sleep apnea equipment provider, raised $150 million in an IPO at $20 a share.

Durham, NC-based Bioventus, the developer of orthobiologics for musculoskeletal conditions, to avoid elective surgeries, raised $104 million in an IPO at $13 a share.

New York-based Kadmon Holdings took on $200 million in debt.

Regulatory Action

Eli Lilly won FDA Emergency Use Authorization for the neutralizing antibody combination of bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) and etesevimab (LY-CoV016) for COVID-19. It’s for mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients at high risk of progression to severe disease. The FDA is also allowing a shorter infusion time of 16 or 21 minutes, compared with the previous 60 minutes, which ought to make the infusion more practical in a pressure-packed hospital environment where minutes count.

Regeneron said it won FDA clearance to market evinacumab-dgnb (Evkeeza), a monoclonal antibody directed at ANGPTL3, as a treatment for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia – a rare genetic disease that results in elevated cholesterol levels and raises the risk of heart attack, stroke and death. A couple days earlier, Regeneron won FDA clearance for cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo), a PD-1 inhibitor for advanced basal cell carcinoma for patients who have previously gotten a hedgehog pathway inhibitor, or for whom that kind of medicine isn’t appropriate.

The FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted against approval of Merck’s PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) as a neoadjuvant treatment for high-risk, early-stage triple-negative breast cancer in combination with chemotherapy after surgery. The data were premature, leaving the door open to a future reconsideration.

Personnel File

Cambridge, Mass.-based Surface Oncology promoted Robert Ross to president and CEO. He was previously chief medical officer. Current CEO Jeff Goater will remain chairman of the board.

South San Francisco-based Cortexyme, the developer of a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, promoted Chris Lowe to chief operating officer and chief financial officer.

Cambridge, Mass.-based Synlogic named Lisa Kelly Croswell to its board of directors. She is senior vice president and chief human resources officer for Boston Medical Center Health System.

Cambridge, Mass.-based Dewpoint Therapeutics named Joel Sendek as its chief financial officer. He was previously CFO at Sema4.

San Francisco-based Lyell Immunopharma, a developer of T cell therapies for solid tumors, hired Charlie Newton as chief financial officer. He was previously with BofA Securities as a healthcare investment banker.

Vancouver, BC-based AbCellera, the antibody discovery company, promoted Ester Falconer to chief technology officer. She was previously head of R&D.

Eli Lilly said Anat Ashenazi has been promoted to chief financial officer, replacing Josh Smiley, after learning of “an inappropriate personal relationship between Mr. Smiley and an employee.”

Los Altos, Calif.-based Retrotope, a company working on degenerative diseases, said Rick Winningham has been named its new chairman of the board. He’s the chairman and CEO of Theravance Biopharma.

Gilead’s Kite Pharma cell therapy unit said Frank Neumann has joined as senior vice president and worldwide head of clinical development. He replaces Ken Takeshia, who is leaving the company at the end of February.

Cambridge, Mass.-based Gemini Therapeutics hired Brian Piekos as chief financial officer. The company is working on precision medicines for age-related macular degeneration.

Berkeley, Calif.-based Caribou Biosciences, a CRISPR genome editing company focused on CAR-T and CAR-NK cell engineering, hired Jason O’Byrne as chief financial officer. He was previously SVP of finance at Audentes Therapeutics.

UK-based Exscientia, an AI pharmatech company, named Elizabeth Crain to its board, along with Ben Taylor, the company’s chief financial officer.

Deals

Gilead Sciences and its partner, Belgium-based Galapagos NV, said they are shutting down the Phase III trials of ziritaxestat in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A Data Safety Monitoring Board recommended the trials be halted. The latest failure comes after another Gilead / Galapagos partnered program, filgotinib for rheumatoid arthritis, was rejected by the FDA. The partnership was originally valued at $5 billion in 2019.

Dallas-based Taysha Gene Therapies announced a pair of research collaborations with the Cleveland Clinic and University of Texas-Southwestern to further develop AAV vectors to carry mini-gene payloads for epilepsy and other CNS diseases. Terms weren’t disclosed.

AbbVie agreed to work with Berkeley, Calif.-based Caribou Biosciences on CRISPR-based genome editing programs for CAR-T cell therapies. Caribou is pocketing $40 million upfront.

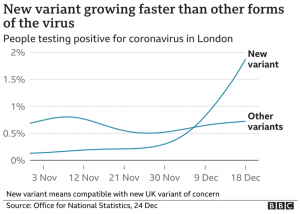

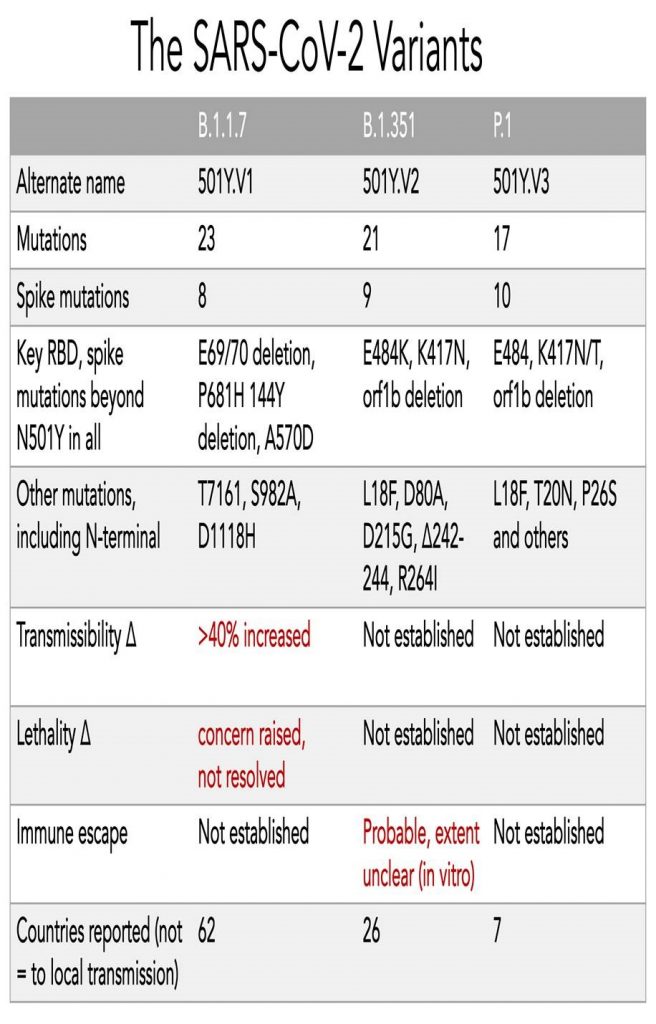

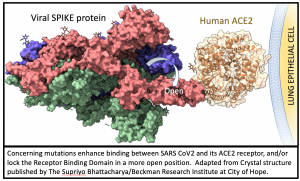

All mutations that are incorporated into virus strains that spread out geographically and grow faster than their predecessors are a “smoking gun”. This is exactly what has happened in the United Kingdom over the past three months and may be happening again in South Africa. The most recent analysis of the UK strain (B.1.1.7; aka VOC-202012/01; aka 20B/501Y.V1) combines prior laboratory findings (

All mutations that are incorporated into virus strains that spread out geographically and grow faster than their predecessors are a “smoking gun”. This is exactly what has happened in the United Kingdom over the past three months and may be happening again in South Africa. The most recent analysis of the UK strain (B.1.1.7; aka VOC-202012/01; aka 20B/501Y.V1) combines prior laboratory findings (