Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

26

Nov

2021

Omicron Variant: the Latest Twist in the Pandemic

Otello Stampacchia, founder, Omega Funds (illustration by Praveen Tipirneni)

I hope you all had a wonderful Thanksgiving.

My Thursday started with me waking up in anticipation of a delightful meal with family (I love apple pie with gelato), at least partially reunited for a holiday meal together after so many months of caution and precautions. I was really looking forward to not having to do much else but drink (Barolo, of course) and be merry for a couple days.

That ended very quickly as soon as I opened my Twitter account.

As background, I do follow quite a few (several hundred by my latest account) virologists and epidemiologists there. They were all freaking out. In the literal sense of the word. (Yes, if you really thought all my previous writings came from “original” research, sorry to disappoint: the views below are more of a synthesis of data generated from the real experts).

As you probably all know by now, there is a new viral variant of concern (B1.1.529) detected in samples from various African countries (particularly South Africa and Botswana, which also happen to be the very few locations in Africa performing PCR testing and genomic surveillance for emerging variants of concern). The WHO in Geneva called for an emergency meeting about it, happening as I write. Also as I write, the new variant has been detected in Hong Kong (due to two returning passengers, at least one flying in from Johannesburg), and Belgium (passenger from Egypt) and Israel, in addition to other African countries.

Incidentally, the global community focused on pandemic surveillance has really stepped up its game in the last 18 months. The B.1.1.529 variant was only identified on Nov. 23. Within 3 days, with a lot of people doing a lot of work on it, information is flowing seamlessly through the global scientific community (which is not what happened early on in the pandemic). We have been helped by the good fortune that this variant can be easily identified by widely available PCR tests, without requiring deep genome sequencing.

I will attempt to summarize below why everybody who knows anything about the pandemic is in a tizzy about it, the potential implications for the long-term perspective for the pandemic, and then try to wrap all this up in my usual optimistic farewell message (note the sarcastic tone in the latter part of the sentence).

Omicron Variant and its properties

The variant was first detected in South Africa. It bears repeating that just because a variant is detected in a country, it does not necessarily originate in that country or that it is somehow the place to blame. South Africa is one of the very few African countries with a proper surveillance mechanism in place that can detect / sequence such strains. The irony of the situation is that countries that are “doing the right thing” sharing data and information in real time are often condemned / ostracized and bear the economic brunt of travel bans etc., instead of being congratulated and offered any support needed. The discussion on travel bans is above my pay grade, to be honest, but we cannot expect countries to collaborate in a global pandemic if their honesty is rewarded with economic shocks.

I would also like to publicly acknowledge and thank the (many) scientists working selflessly on the task: particularly Tulio de Oliveira (@Tuliodna, one of the best Twitter handles ever), Director of CERI (Centre for Epidemic Response & Innovation, South Africa). Developed countries need to continue and increase investments in collaborating with such centers across the world and providing them with resources. This is an absolute priority and the US and EU need to step up.

That said, and as mentioned previously (in July 2021 by both Larry Corey and yours truly here in Timmerman Report), Africa is a fabulous breeding ground for the virus, due to a large population (1.2 billion as of 2016), with low vaccination rates, and very high prevalence of HIV-positive people and other large immune-compromised, susceptible patient populations.

These conditions predispose some infected individuals to incubating the virus over a long period of time, increasing the probability of breeding viral escape variants. By the way, similar conditions also exist in several developed countries due to a meaningful percentage of the population with co-morbidities (diabetes, obesity, etc.), vaccine deniers etc. etc.

OK, so you knew all that, apologies: let’s get to the fun / scary / geeky part .

What then has all my virologist and epidemiologist “friends” in a frenzy?

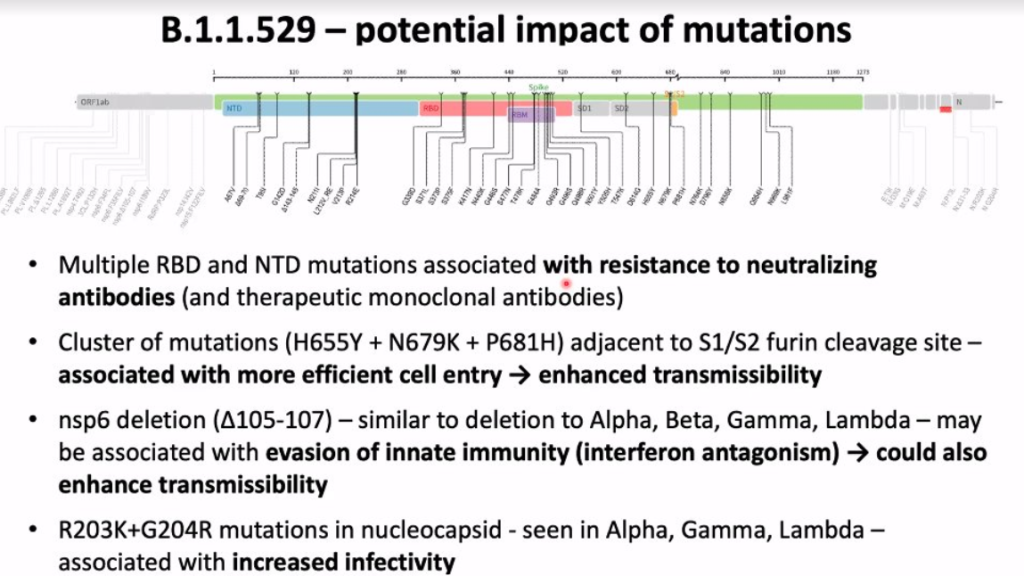

Omicron has a lot of mutations (50) across its sequence: see graph below.

Just the spike protein (which binds to the ACE2 receptor on human cells) has 32 mutations across its receptor binding domain (RBD) and the furin protease cleavage site. It pretty much looks like all the “greatest hits” from Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta have been put together in a new “compilation”, plus some new “tracks” (mutations about whose potential effects we have no idea).

This unique and broad mix of changes in the spike protein comprises quite a few previously known to affect receptor binding and escape from neutralizing antibodies. There are many more mutations across other viral sequences associated with increase transmissibility and (quite possibly) more efficient evasion / escape from recognition by the immune system.

That alone would not have been sufficient to freak me (and many people way more knowledgeable than me) out. After all, there have already been several variants like Gamma (South America) and Beta (also from South Africa), for example, which had mutations that were supposed to provide an advantage in escaping the immune system.

They all got eventually outcompeted by Delta, which is extremely transmissible and produces many more viral particles upon infection due to its higher fusogenic (and other) properties. Delta, and its many offspring, was basically king of the land (and it still is pretty much everywhere). So far, however, we have been very fortunate that Delta hasn’t been able to evade the vaccines’ protective effect, at least over a 5-6 months period in healthy / young subjects.

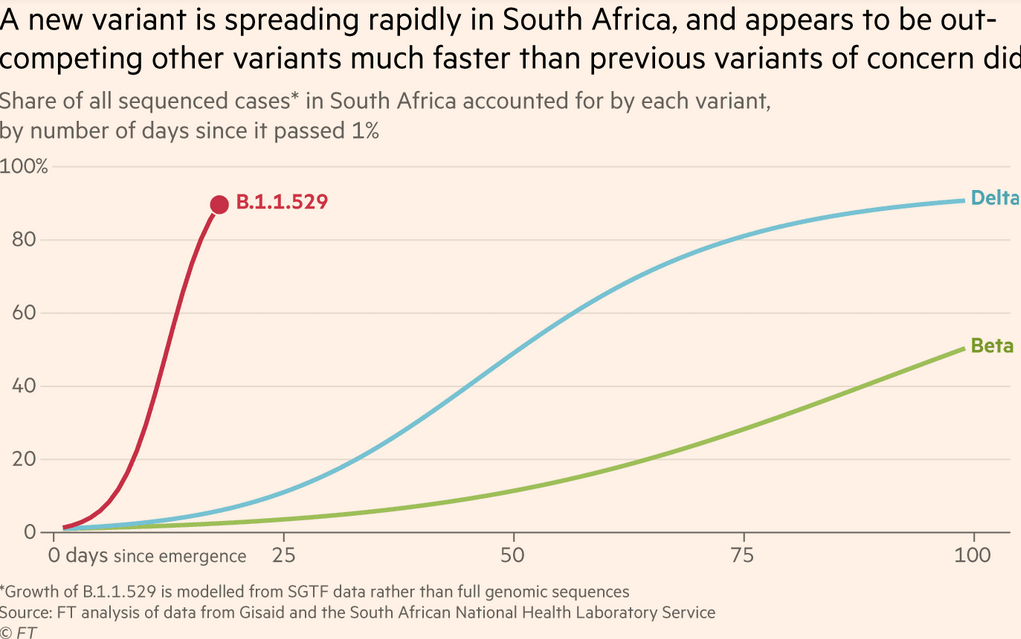

What DID freak me out is the second graph below from the Financial Times: Omicron seems to be increasing its prevalence AND incidence very rapidly in a Delta prevalent background.

Daily COVID cases have more than tripled in S. Africa since Tuesday of this week, and apparently (take this with a pinch of salt) close to 90% of cases seem to due to Omicron in the province where it has been detected. That suggests it might be able to outcompete Delta and be more transmissible. See also this brilliant thread from John Burn-Murdoch, data scientists and visualization genius at the Financial Times.

If you want to escape your family obligations during this holiday, I also highly recommend reading the GISAID report on the new variant on Nov 23, or the just published UKHSA report and technical briefing (skip to page 18 if you are impatient like me): the number of mutations is mind-boggling indeed.

We obviously do not know for sure how much more transmissible Omicron is, or how effective currently approved vaccines and monoclonal antibodies will be against it. These experiments are lengthy and not trivial to perform. The in vitro experimental data should be available shortly, followed by animal “challenge” studies, but neither will be the last word on the key question — do the vaccines hold up against the new variant in people, especially over extended periods of time? We should hopefully have some answers within 2-3 weeks.

I’d like once again to remind people that, in a pandemic, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Nature has a good summary of the known unknowns here.

Potential implications and the long-term perspective

First of all, I sincerely hope that Omicron will not be able to outcompete Delta globally. If it does, as I fear, and if it shows increased capability for immune evasion / escape, then we might be in real trouble. It would force the vaccine makers to create new vaccines purpose-built for the new variant, and they might have to be administered more frequently.

Luckily, we have had some much earlier warnings than we had with Delta, thanks to a strengthened global surveillance system (Delta was already all over the world by the time people started paying attention).

This could buy us a few weeks, perhaps a few months, if we are lucky.

We have also managed to somehow scale up the manufacturing capabilities for vaccines. But this would represent a big stress test. We would have to possibly re-vaccinate everybody with Omicron-specific additional doses. Were the new vaccine to require a 3-dose regimen over a 6-month period, as many virologists and immunologists would expect, it could be too much for our global manufacturing capacity. I do not think it is possible to have half yearly dosing for the whole world.

We are also still left with the problem of immune-deficient / compromised people as new source of variants: we are talking tens of millions of people, if not hundreds of millions, worldwide. Vaccines’ protective effects do not seem to last as long in these individuals. They will keep helping the virus get fitter and fitter by incubating it over months and allowing it to build much better versions.

In the hopeful case that I am wrong, however, this new variant should (if needed) raise the alarm to code red.

Up until (very) recently, most developed countries (US and Western Europe) have been lulled in a state of complacency, believing this pandemic was more or less over, with politicians being pushed by significant portions of their populations to remove / lighten up the various mitigating procedures that have proven successfully in containing the spread.

All this, just as we are entering the fall / winter period in the Northern hemisphere, with associated indoor spreading due to poor ventilation, and large portion of the population still unvaccinated (tragically so in Eastern Europe and large parts of the US with low levels of trust in public health authorities). And, for those of you who have forgotten this, this will be the first winter season with the highly transmissible Delta variant being the prevalent strain.

One silver lining: orally available polymerase inhibitor / protease inhibitor treatments from Merck and Pfizer (respectively) have so far delivered excellent efficacy and are likely to hold up well against the variants because of their different mechanism of action. These treatments are no substitute for vaccines in the general population, but they will provide an additional useful tool for global pandemic defense because of their ease of use, ease of manufacturing, and ease of distribution.

That said: they cannot be given to people in a chronic setting (like immune-compromised patients); Merck just announced very puzzling and honestly disappointing protection data from the second part of their study; AND, people would need to be diagnosed very quickly for the anti-virals to be effective. As a result, while invaluable, I do not think they will actually help meaningfully containing spread or the emergence of new variants.

Conclusions: the never-ending pandemic?

Practically, then, what to do right now?

I am afraid we do not have the luxury any more of caving to the (very vocal) minorities of vaccine deniers / libertarians imposing the (supposed) pre-eminence of individual liberties over public health considerations.

We should impose vaccine mandates ASAP, mask mandates in public / indoor places, mandate vaccine passes, improve PCR and rapid antigen testing infrastructure, etc.

In addition, we should:

- Strengthen vaccine availability / vaccination rates in developing countries;

- Make abundant foreign aid available (subject to vaccine adoption rates, perhaps);

- Adapt and prepare our public health infrastructure for much broader testing requirements

- Prepare for the very real possibility of yearly / half yearly vaccine shots with regularly updated sequences;

- Turbo-charge antibodies / oral small molecule anti-virals research;

- Expand monoclonal antibody manufacturing capacity for what is likely to be a huge requirement for prophylactic options for immune-compromised populations who are unlikely to mount an adequate vaccine-induced immune response.

And this, by far, is not an exhaustive list.

I am, however, exhausted just by thinking about it and by how much time and treasure, not to mention lives and livelihoods, has been wasted already.

My wish list above, similar to my requests to the Italian equivalent of Santa Claus as a child, is extremely unlikely to be granted, particularly the societal changes / mandates mentioned. It might have, perhaps, a slightly higher probability of happening in selected countries in Western Europe (I was very encouraged by the recent Austrian vaccine mandate across its population, for example: a first in developed countries). I just do not see this happening in the US or the UK.

This will likely condemn us to flare ups in cases / hospitalizations / deaths for years to come, particularly in the fall / winter months (and in the “air-conditioned” months in places with very hot summers).

While science has delivered above and beyond expectations, our society has shown itself unable to accept the sacrifices needed to effectively fight an enemy that exploits our medical and cultural vulnerabilities and becomes ever fitter. This is painfully particularly so in Western Democracies with our (just) emphasis on open debate and cultural diversity that is perhaps willfully manipulated by minorities / geo-political actors / lobbies using social media echo chambers.

We are all actors now, in a Darwinian evolution drama with many acts: the fittest, as always, will survive.

Follow Otello Stampacchia on Twitter: @OtelloVC

This article expresses the personal views and perspectives of the author. The views and perspectives expressed here do not necessarily represent the views or perspectives of Omega Fund Management, LLC or any officer, director, partner, member, manager or employee of Omega Fund Management, LLC or any of its affiliated entities.