Get In-depth Biotech Coverage with Timmerman Report.

21

Dec

2020

More Than Words. Taking Steps Together Towards Greater Health Equity

Nina Kjellson, general partner, Canaan Partners

Healthcare leaders have made many commitments this year on racial equity.

The question now is how we turn words into action.

Over the past couple years, I’ve become a believer in the power of small groups that share an immersive, cultivated experience.

In September, I convened one such group on a two-day virtual journey to Montgomery, Alabama. This virtual conference grew out of my work on Impact Experience//Health Equity. It’s a partnership born of an Aspen Health Innovators’ fellowship in collaboration with longtime equity educators, Impact Experience.

The trip to Montgomery was inspired in part by the experience a few of us biotechies had in climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro for cancer research at Fred Hutch. On that trip in summer 2019, all 14 men and all 13 women made it to the summit of the highest peak in Africa (elevation 19,340 feet). It wasn’t always easy. But coming down, we realized we had forged a cohesive family committed to each other’s well-being and success. Our email threads and Zoom reunions ever since have been a vibrant reflection of community born of sweat and struggle and revelations shared step by step.

My recent tour of Montgomery, with a couple friends from the Kilimanjaro climb, was the start of a new journey. We sought to trace the roots of structural racism in health care and what can be done about it.

This conference was unlike anything we had attended before. Our collective horror at the murder of George Floyd and Brianna Taylor, on top of the mounting evidence of the unequal toll of the COVID pandemic — both economic and health-wise — turned discomfort into moral outrage. We started to see inaction as complicity.

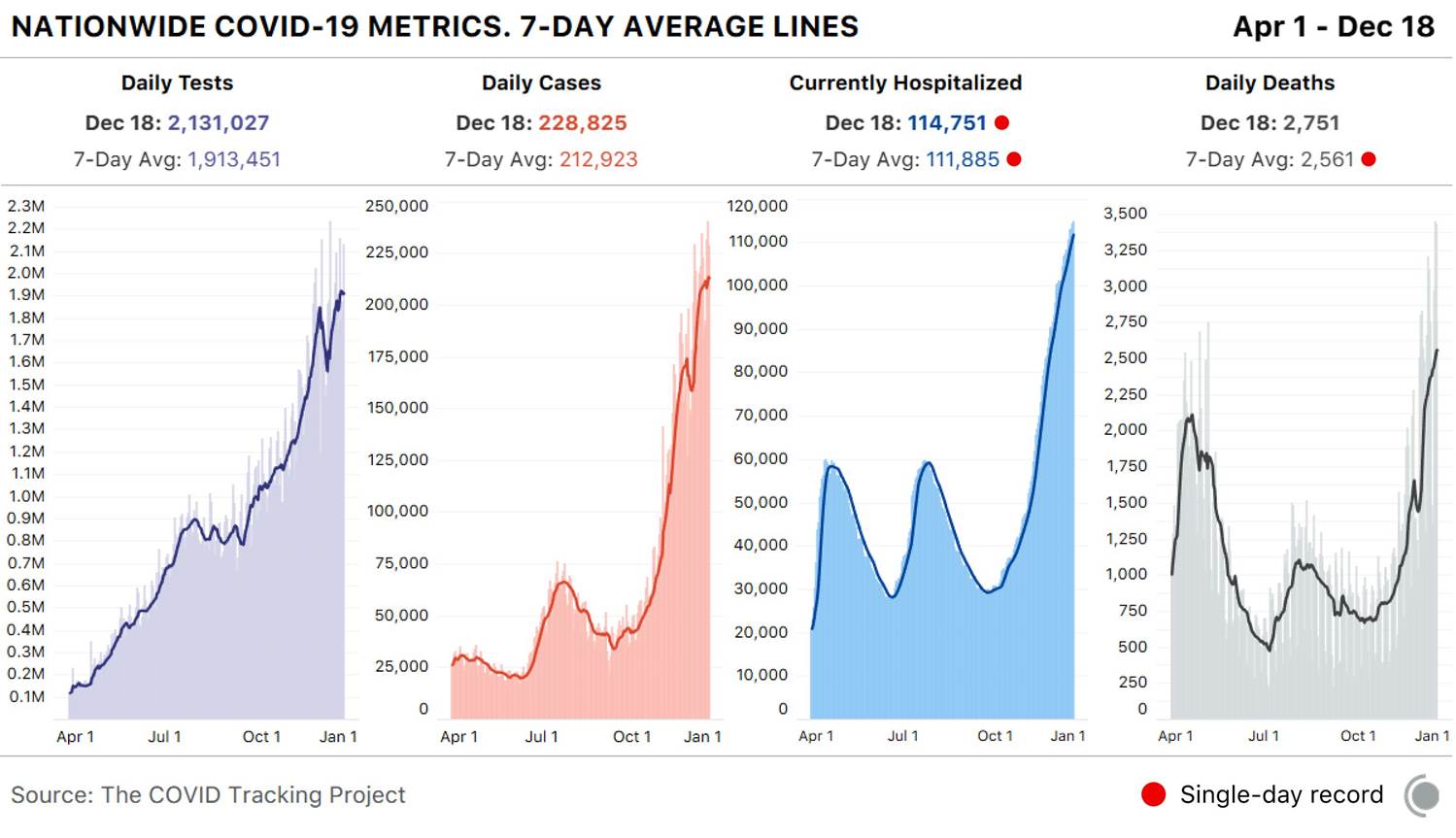

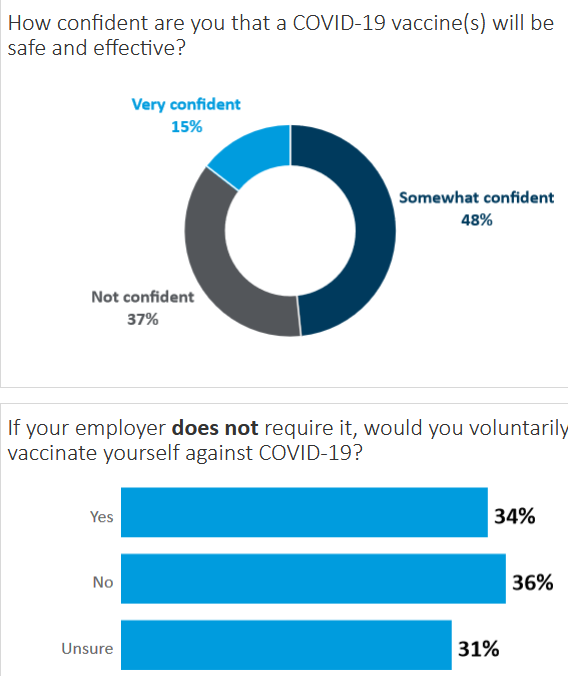

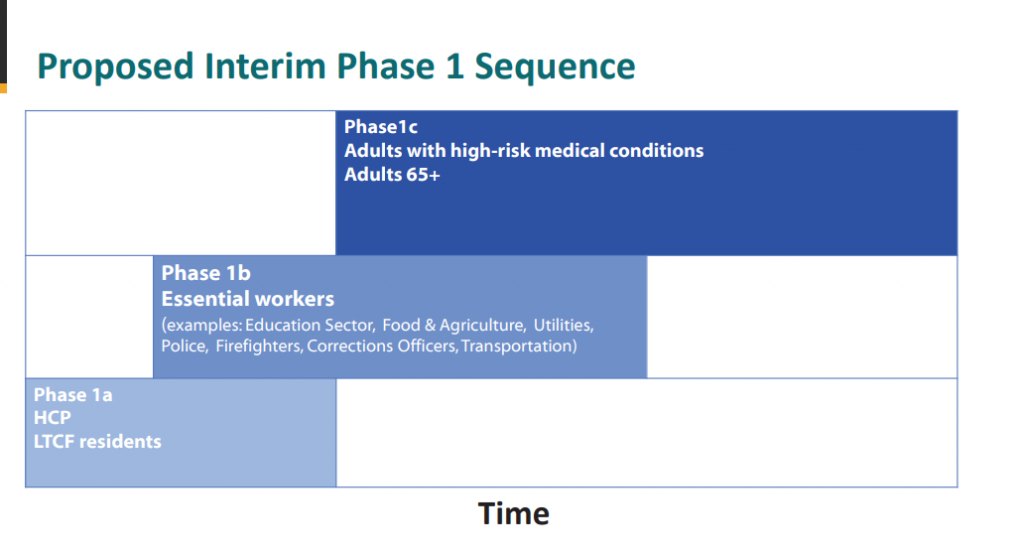

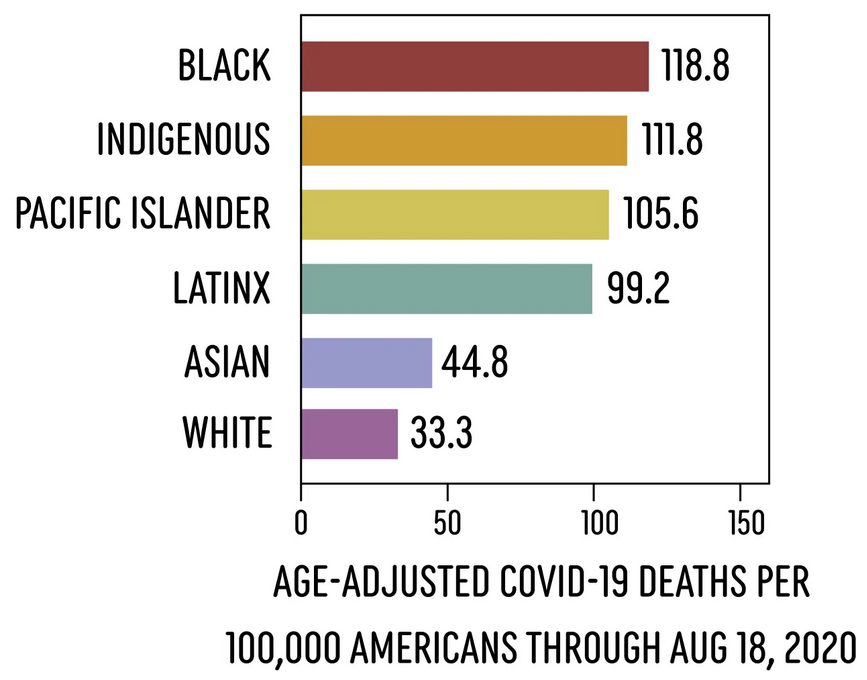

Consider some data:

Data analyzed by APM Research Lab.

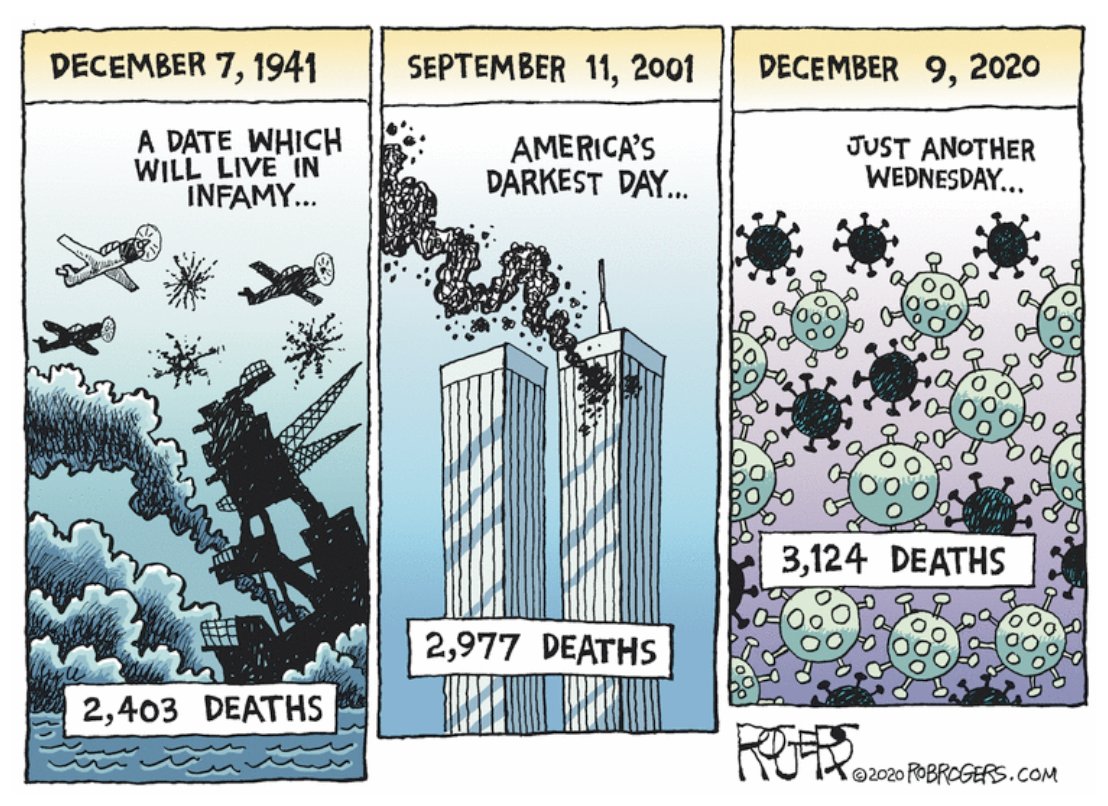

- If death rates from COVID were equal by race, 20,000 Black and 9,000 Latinx Americans would still be alive right now.

- Many more young BIPOC people are being hospitalized and dying of COVID-19 as compared to white populations, despite younger people having much less risk of severe symptoms or mortality. (Source: APM Research Lab)

- Over 70% of Black and 60% of Latinx households report serious financial problems during the pandemic compared to just over a third of white households (36%) and 40% of Black and 60% Latinx households report job loss, furloughs or wage cuts during this time. (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation)

- Black and Latinx households have been statistically more likely to experience food insufficiency throughout the pandemic with shortages increasing over time. (Urban Institute)

As scientists and biotechnologists, we know well that these disparities are not rooted in biology. Melanin and a few continental alleles can’t explain the drastic differences in predisposition, access, experience and outcome with respect to health care and the many other institutions that determine health and social status.

Neither does income or education explain the disparities. We know, for instance, that fetal and maternal health outcomes for Black women are still well below those for white women when normalized for earning and academic achievement. Pregnancy related mortality for Black women with a college degree is 5 times that for their white counterparts. FIVE times. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Some disparity may be explained by a distrust and voluntary avoidance of the health care system leading to the delayed diagnosis and treatment of serious diseases such as cancer. Blacks have higher death rates from most cancers than all other racial/ethnic groups. Despite similar rates of breast cancer, Black women are much more likely than White women to die of the disease, according to the National Cancer Institute.

If this is because of a reluctance to seek care, might this be the legacy of James Marion Sims, the Tuskegee trials or the Flexner Report’s elimination of Black medical colleges (here and here)?

Like any journey, it has to start somewhere. This one begins with education and awareness. The Impact Experience//Health Equity program is comprised of pre-curriculum, a guided (virtual) tour, community-member engagement, moderated seminars with expert faculty and group and individual exercises. But it wasn’t all about content. The two days were interspersed with unstructured time for music, art and conversation. We crafted the program to cover history, current events, social and emotional learning.

Our vision is to catalyze both a committed peer cohort and firm action plans for implementing change.

We had an initial group of 29 participants on our virtual journey to Montgomery. These people were leaders from biopharma, pharma, diagnostics, academic medicine, health insurance, public health, venture and public investing and management consulting.

To a person, the reviews on the experience were exceedingly positive – for the depth of exploration, space for personal introspection and group activities imagining – and charting – a future free of implicit and structural bias.

In follow-up conversations over the past three months, we have seen a great deal of camaraderie, including local e-meet-ups and projects. We are seeking to hold ourselves accountable to the goals we’ve set for our companies and ourselves. We’ve had deep debriefs of the experience, in order to spread what we’ve learned throughout our organizations.

We’re insisting on concrete actions like implementing new ways of hiring and training, tools for recruiting diverse participants in clinical trials, criteria for selecting minority-owned vendors and new approaches to talking about race and equity.

Everyone, of course, is busy. Two days might seem like a lot to commit to a seminar or continuing education program. But the time allowed for immersion not just in the curriculum, but also for building relationships among peers.

There’s something special about getting to know professional peers on a personal level. The level of intimacy that emerged was striking. Participants shared personal experiences of bias, racism, and hard-fought assimilation into power hierarchies. This was essential to breaking down barriers and confronting one’s own implicit biases.

These are the kind of raw, deeply felt conversations that rarely surface in the corporate environment.

These meaningful conversations translated into clear actions. New internship programs were established. Some of us redirected, or increased, our personal and corporate giving.

The structural barriers that exist in our sector runs deep – from the way we train, teach, architect and even structure information. Medicine, historically, hasn’t anticipated including women or people of color in leadership.

Health care emerged as a sector within a historical, societal, and cultural context. It will take many years and much effort to undo bias and reinvent the field. The journey we took as a group to Alabama started with the 250-year history of enslavement, the next 100 years of the Jim Crow era, followed by the Civil Rights era of the 1960s to the present. We can’t begin to understand the health disparities of today, and the potential solutions, unless we understand this arc of American history.

The distance we traveled together, from our heads and deep into our hearts, gives me great hope that we as leaders can accelerate change. There are things we can all do, from grass roots solutions all the way through helping advance legislation at the state and federal levels.

And if the moral calling isn’t the motivation, then the markets and business needs will compel us.

Over the next 10-20 years, more than half the US population will be self-described as other than white, according to the US Census Bureau. This means the demographics of our studies, employees, patients, payers, regulators, investors will be shifting. Study after study has shown financial and compliance outperformance by companies with greater gender, racial/ethnic and immigration diversity. A McKinsey report from 2017 found a 33% likelihood of EBIT outperformance by companies with ethnic and cultural diversity and 21% higher profitability from companies with above average gender representation on executive teams.

As we reflect on 2020 – and the ways in which we have been moved by this difficult year – I hope we can take the moments of awakening and make them into movements towards a more equal, equitable and healthy world. (Whether out of love, righteousness or business-interest).

You can join networks like this, to spark movement in your spheres. You can create this kind of momentum.

I’m getting ready for another Impact Experience//Health Equity. The next journey is in March. We are seeking to turn the words of 2020 into the actions of 2021.

Interested? nina@canaan.com

If you are making your year-end charitable giving list, please consider Life Science Cares. We are channeling funding and volunteerism from the life science community to close the needs gaps in Boston, Philly and the San Francisco Bay Area. Our focus is on homelessness, hunger, STEM education and internship and workforce opportunity with an emphasis on diversity. Please make a note designating geography of interest. https://lifesciencecares.org/donate/